According to the syndrome model of addiction (see The WAGER 10(1) ), each person has a unique combination of three primary types of influences and risk factors for the development of addiction: biological, psychological, and environmental. Researchers have learned about biological influences, such as genetics (see WAGERS 3(30), 3(34), 11(2), and DRAM 1(3) among others), as well as psychological influences (see WAGERs 8(2), 8(23), and DRAMs 2(4) and 2(5), among others). Researchers are also exploring the influences of social setting on the development of addiction. For example, this week ASHES reviews a recent study by Peterson, Leroux, Bricker, Kealey, Marek, Sarason, and Andersen (2006) that examined the influence of parental smoking on children and adolescents.

Peterson et al. successfully recruited 3,283 children and their parents from two consecutive third grade enrollments in 20 Washington State school districts; of these families, 92% agreed to participate. All children, for whom the smoking status of both parents or guardians was known at baseline, were eligible to participate. Parents of 3,012 children completed a Parent Information Form, which included questions about smoking status and familial relationships between parents and child; 82.9% of the parents returned the survey. Of these respondents, 85.9% were female; the responding parent provided information about the non-responding parent. Researchers tracked all children for the follow-up survey, completed 9 years after baseline when the children were in 12th grade (including children who dropped out of school); 95% of the baseline children agreed to participate in follow-up. Children completed surveys in class. Saliva samples confirmed recent cigarette smoking. Those who were absent or who had dropped out of school, completed phone surveys 1-2 weeks later.

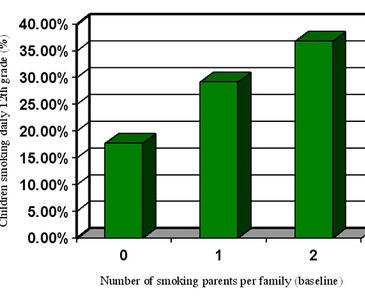

At baseline, both parents smoked in 520 of the families (17.3%), one parent smoked in 802 of the families (26.6%) (276 mothers (34.3%) and 526 fathers (65.6%)), and no parents smoked in 1,690 of the families (56.1%). Of the children interviewed at follow-up, 23.9% (685 children) admitted to daily smoking, which is slightly higher than the national average of 21.4%. Of the children who reported smoking in 12th grade, 17.7% grew up in non-smoking families; 29.2% grew up in families with one smoking parent; and 36.8% grew up in families in which both parents smoked.

FIGURE. PERCENTAGE OF CHILDREN SMOKING BASED ON NUMBER OF PARENTS SMOKING AT BASELINE (ADAPTED FROM PETERSON ET AL., 2006). Click image to enlarge.

According to the results of this study, children with one smoking parent were 1.90 times more likely to smoke daily compared with children of non-smoking parents; children with two smoking parents were 1.39 times more likely to smoke daily compared with children with one smoking parent; and children with two smoking parents were 2.65 times more likely to be daily smokers than children of non-smoking parents.

There are several limitations to this study. The study sample includes predominantly Caucasian families who live in rural communities within the state of Washington; this limits the generalizability of the results. This study sample might not be representative of other parts of the country. Further, only one parent completed the baseline questionnaire and answered questions about smoking status for both parents. This might compromise the validity of the data. Also, researchers did not collect data after children reached the age of 18. As a result, we do not know the impact of parental smoking on these children as adults. No data were collected on parental smoking status after baseline, and therefore the impact of changes in parental smoking is unknown.

Nonetheless, the results of this study suggest that there is a causal relationship between the number of smoking parents and the likelihood that a child will begin to smoke—parental smoking seems to be a significant risk factor for adolescent smoking. This finding has significant implications for prevention efforts directed at adolescents. To address teenage smoking, it might be most effective to involve entire families in smoking prevention and treatment efforts, and it might prove especially important to direct smoking cessation efforts toward parents. Further research needs to examine the familial dynamics that impact the development, or lack thereof, of daily smoking among adolescents. It also might be important to determine whether this relationship between the actions of parents and children is universally present across all expressions of addiction. If so, it would be important to incorporate families into treatment and prevention of other addictive behaviors.

–Siri Odegaard.

References

Peterson, A.V., Leroux, B.G., Bricker, J., Kealey, K.A., Marek, P.M., Sarason, I.G., et al. (2006). Nine-year prediction of adolescent smoking by number of smoking parents. Addicitive Behaviors, 31(5), 788-801.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.