“The important thing in science is not so much to obtain new facts as to discover new ways of thinking about them…” — Sir William Bragg (1862-1942)1

Currently, the dominant philosophy of addiction presumes that particular chemicals are inherently addictive. This view suggests that the psychoactive property of the drug causes addiction. The conventional wisdom suggests that the use of a psychoactive substance leads directly to abuse, dependence and inevitably addiction with all of its associated impairments. The only uncertainty is how long it will take to become addicted. Guided by this approach, the treatment and diagnosis of addiction has been specific to substances, and tailored to the assumption that dependence, characterized by neuroadaptation (e.g., tolerance and withdrawal), and addiction are necessarily related. However, new research reveals that there are common underlying characteristics to many different manifestations of addiction, including behavioral expressions of addiction such as excessive gambling. Further, dependence and addiction are not necessarily mutually inclusive. For example, one can have an addiction without being dependent on dependence producing drugs (e.g., gambling); similarly, one can become dependent on drugs without developing addiction, (e.g., using opioids for post-operative pain relief even though neuroadaption has occurred). Taken together, this evidence suggests that various forms of addiction arise from similar causes, and that the specific objects of addiction (e.g., cigarettes or slot machines) are less important to the development of addiction than previously thought.

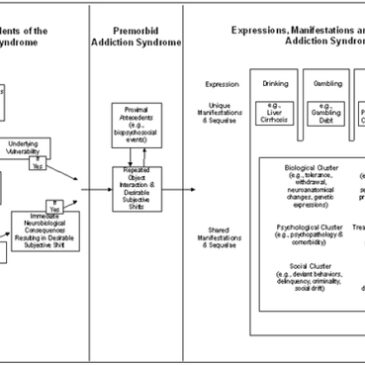

This new understanding makes room for a broader characterization of addiction that includes both substances and behaviors. A recent article (available for download on the DOA web site) by Shaffer, LaPlante, LaBrie, Kidman, Donato, and Stanton (2004), proposes a syndrome model for classifying addiction; the authors define syndrome as “a cluster of symptoms and signs related to an abnormal underlying condition,” (Shaffer et al., 2004, p. 3). This system of classification incorporates the risk-factors and consequences common to all addictions, and simultaneously accounts for the elements that distinguish various forms of addiction from one another.

According to Shaffer et al.’s syndrome model, all addictive disorders generally follow a particular developmental pattern. That is, addiction seems to arise from similar antecedent risk-factors and develop into addiction as a result of exposure to and experience with different objects of addiction (see Figure 1). Expression of the addiction syndrome depends on the interaction of the individual and the given object of addiction. Shaffer et al. (2004) suggest that a person’s risk for developing an addiction depends on a combination of three factors: personal vulnerabilities (e.g., genetics), exposure to an object or activity, and one’s experiences with that potential object of addiction.

Figure 1. Model of the Addiction Syndrome (adapted from Shaffer, LaPlante, LaBrie, Kidman, Donato & Stanton, 2004)

According to the syndromal model of addiction, when repeated exposure to, and interaction with, a substance or activity consistently leads to a desired neurobiological and/or social response, a person becomes at-risk for developing an addiction. Within this ‘premorbid’ phase of the syndrome model people teeter on a delicate balance and have the potential to shift from risky behavior to addictive behavior.

Once the syndrome emerges, manifestations of an addiction simultaneously reflect the object of addiction (e.g., the symptoms and consequences of a smoking addiction will be somewhat different than those of a gambling addiction, by the nature of the activity and substance involved), and more general characteristics of addiction (e.g., depression, withdrawal, etc.), as shown in the figure above.

Evidence supporting such a model is accumulating. Studies have shown that both genetics and brain function contribute to a person’s vulnerability to addiction, though not necessarily for a particular substance or behavior (Karkowski, Prescott, & Kendler, 2000). Further, studies have found that the presence of particular psychiatric disorders might make a person more vulnerable to addiction. For example, those who seek treatment for substance abuse generally have a higher rate of anxiety and depressive disorders (Silk & Shaffer, 1996); similarly, those struggling with major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, etc., often have a higher rate of alcohol abuse and drug use disorders (Merikangas et al., 1998).

Additionally, addictions seem to follow similar patterns of improvement, relapse and remission. Because syndromes are sometimes recursive, symptoms or expressions of a particular manifestation of the syndrome can influence current antecedents of addiction or develop into antecedents for another addiction. This could explain why a person struggling with one form of addiction often struggles with others as well. A syndromal model accounts for the fact that there are common risk factors for addiction in general but not for particular substances or behaviors, and why treatments designed to address a particular addiction are often effective in treating problems with seemingly unrelated substances and behaviors.

Though there are important aspects of the model that remain to be tested, current research strongly supports the idea that there is a common etiology for all additions. It is with this model for addiction in mind that we present the BASIS website to you. The aim of the BASIS is to provide the general public, treatment providers, policy makers, and other interested individuals with free direct access to the latest scientific information and resources on various expressions of addiction.

Comments on this article can be addressed to Siri Odegaard.

Notes

1. Bragg SW. copyright 1995-2003 Jone Johnson Lewis. Available at: http://www.wisdomquotes.com. Accessed October 1, 2003

References

Karkowski, L. M., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Multivariate assessment of factors influencing illicit substance use in twins from female-female pairs. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 96, 665-670.

Merikangas, K. R., Mehta, R. L., Molnar, B. E., Walters, E. E., Swendsen, J. D., Aguilar-Gaziola, S., et al. (1998). Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the international consortium in psychiatric epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors, 23(6), 893-907.

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R. C., Donato, A., & Stanton, M. V. (2004). Toward a syndrome model of addiction: Multiple manifestations, common etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(6), 367-374.

Silk, A., & Shaffer, H. J. (1996). Dysthymia, depression, and a treatment dilemma in a patient with polysubstance abuse. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 3, 279-284.

The Linden Method Girl August 12, 2010

honestly, isn’t every human being addicted to something? its something rather innate. i think the actual problem can be found within the actual diagnoses procedure. clinicians now a days are actually succumbing into a straight forward diagnoses rather than taking into account the psychosocial aspect of the disorders. with this in mind, how many worng diagnoses have already been made? the schaffer model does mention about how behaviour contributes towards a certain “action” but what about the actual genetic side of the individual?which in turn can be influenced either by their surroundings or their previous background?

i honestly find it to be questionable that one can tackle a “disorder” (lets call it that just for the purpose of this topic) in such a straightforward model plan?

Not Moses January 16, 2011

In 24 years of treating substance and process behavior addictions, I have regularly seen poly-addiction and addiction switching in the service of a common belief that one can avoid affects (emotions, sensations, feelings) one believes to be “intolerable” by stimulating him- or herself sufficiently to temporarily “mask off” the “intolerable” affects. Such activity unbalances — and cause structural changes in — the dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin chains in the limbic system, especially in the ventral tegmentum, amygdala, orbital-frontal cortex and hippocampus of (for most people) the right brain hemisphere. This cognitive-affective-neurobiological-behavioral linkage appears to me to be universal in addicts of any sort. Many “Class A” treatment facilities are now using various mindfulness meditation and cognitive restructuring techniques (on top of atypical antipsychotic medications, when needed) to put the kybosh on the self-generation of uncomfortable affects, as well as the addiction-induced, neuroplastic modifications. Every bit as much as the brain can change the mind, the mind can be trained to change the brain. RG, Psy.D.