Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs) are caused by alcohol use during pregnancy. They can lead to birth defects, behavioral disorders, and impaired cognitive development. In the United States, approximately 2-5% of school-aged children are affected by FASDs. By conducting alcohol screenings and brief interventions during pregnancy, health care providers can effectively reduce excessive alcohol use and prevent FASDs. However, providers often feel uncomfortable discussing alcohol use with their patients. The stigma surrounding individuals1 who consume alcohol during pregnancy acts as an additional barrier, hindering open communication from the patient side. This week, The DRAM reviews a study by Saloni Sapru and colleagues that investigated the influence of an educational model that integrated (1) Grand Rounds lectures on FASDs by obstetricians/gynecologists and (2) lived experience presentations from mothers of children with FASDs on FASDs-related stigma and awareness among healthcare providers.

What were the research questions?

How did the combination of (1) the lectures by Champions (i.e., Grand Rounds presentations by obstetricians and gynecologists) and (2) presentations by Speakers (i.e., lived experiences shared by mothers of children with FASDs) influence FASDs-related stigma and awareness among healthcare providers?

What did the researchers do?

The Center for Disease Control allocated funding to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and FASD United to enhance awareness and distribute resources for FASDs prevention. This initiative aimed to address the inadvertent stigma among clinicians working with mothers who consumed alcohol during pregnancy. As a part of the educational campaign, ACOG and FASD United developed a Speakers Bureau, consisting of voluntary Champions (i.e., obstetricians and gynecologists) and Speakers (i.e., mothers in recovery who have a child with FASDs). Between 2019-2022, the Champions and Speakers participated in 100 Grand Rounds presentations. These presentations were divided into FASDs lectures given by a provider, lived experience presentations given by a mother, and Q&A.

Ten Champions and nine Speakers participated in a qualitative interview following these presentations. For the Champions, the interview topics included (1) utility of Speaker’s stories, (2) perceptions of audience reactions, (3) opinions on healthcare provider’s roles in FASDs prevention, (4) experience with referrals and resources for patients using substances, and (5) suggestions for improving this collaborative initiative. For the Speakers, the interview topics included (1) their experience as a Speaker, (2) attendees’ reaction to their personal stories, (3) the intended message of their stories, and (4) their beliefs regarding changing providers’ attitudes based on their lived experience. Researchers used a thematic analysis to analyze the results.

What did they find?

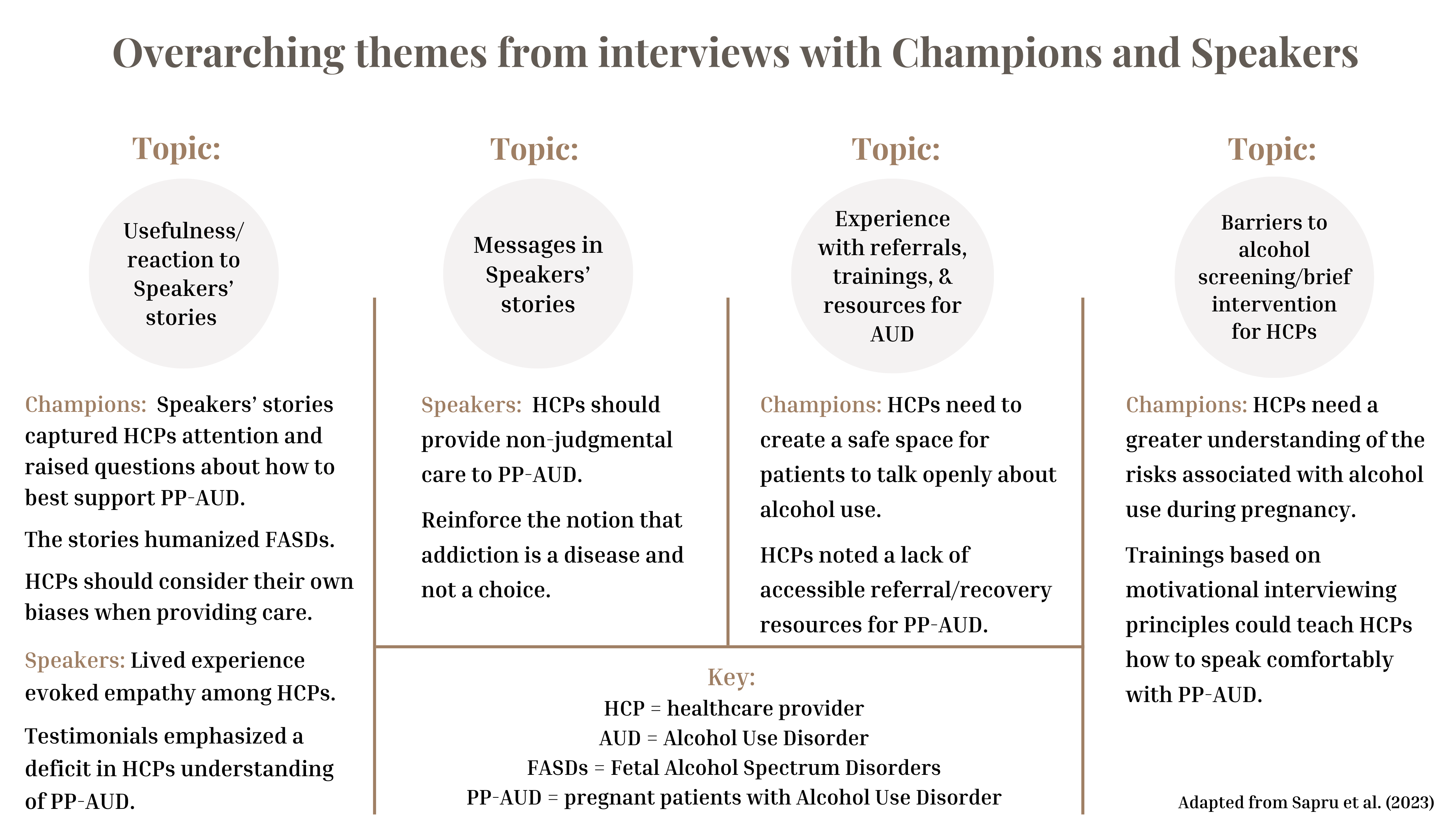

The Champions perceived that when they included Speakers in their presentations, it positively impacted how the audience engaged and understood the information (see Figure). They also acknowledged the power of personal stories in humanizing FASDs, and recognized the important role that lived experience played in challenging stigmatizing perceptions. Similarly, the Speakers felt empowered to educate providers about their role in preventing FASDs. They aimed to convey that addiction is a disease, not a choice, underlying the importance of treatment and support for mothers seeking help. One Speaker proposed a practical step for providers, suggesting that they supply mothers with resources to achieve sobriety. However, providers reported trouble accessing these resources (see Figure). Despite the generally positive responses that Speakers received, some providers still exhibited bias and stigma, questioning if the Speaker would go to jail. Providers could benefit from subsequent training on how to speak comfortably with patients about alcohol use.

Figure. Depicts the overarching themes from interviews with Champions and Speakers. This Figure was adapted from Sapru et al. (2023). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The study underscores the need for educational initiatives, particularly in medical residency programs, to equip healthcare providers with the knowledge and empathy to address FASDs, reduce stigma, and create a non-judgmental environment for pregnant individuals to seek help. The model not only has the potential to enhance emotional intelligence more broadly, but also challenges providers to view alcohol use during pregnancy –not just as an individual problem– but as a social problem intertwined with stereotypes and stigma. Collaborative efforts like this provide a model for widespread dissemination of educational interventions, shifting from a fact-based to an empathy-based approach to learning. This approach is crucial for raising awareness about FASDs prevention and addressing the pervasive stigma surrounding individuals who consume alcohol during pregnancy in a way that emphasizes treatment as opposed to more punitive measures.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The study faced two main challenges. First, the Champions and Speakers interviewed were potentially biased, having volunteered to train providers. This could have potentially led them to have a more positive perception of the program’s effectiveness. Second, the absence of direct data from presentation participants hindered an assessment of the effectiveness of the empathy-based learning approach. To address this, ACOG plans to implement a pre- and post-survey during future Grand Rounds on this topic.

For more information:

FASD United has support resources for individuals impacted by FASDs. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For additional drinking self-help tools, please visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1. We are using this inclusive language rather than “mothers” because we recognize that some trans men, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people give birth. When describing Sapru’s study in particular, we use the term “mothers” because the researchers only studied mothers. Click here to learn more about the importance of inclusive language. Click here to read a study about trans mens’ pregnancy experiences.