Humans are social beings. Behavior that we perceive in others largely shapes our own and creates social norms within communities. A good example of this is heavy drinking in college: students tend to drink based on how much they believe their fellow students drink, and as you might guess, these beliefs are wrong much of the time. Still, social networks are complex, and not everyone in our lives holds the same influence. This week, The DRAM reviews a study by Melissa Cox and her colleagues that investigated how misperceptions of peers’ drinking relate to heavy drinking habits among first-year college students.

What was the research question?

Do first-year college students drink more heavily if they misperceive how heavily their friends and peers drink?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers surveyed 1,313 college students at a university in the northeastern United States, once in the fall of their first year and once in the following spring. Only full-time students living on campus were eligible for the study. In the fall survey, participants nominated up to ten of their peers also participating in the study who they considered “important” (e.g., friends) and estimated how many days in the past month each nominee consumed five or more alcoholic drinks in one sitting, a heavy drinking day. Participants then estimated this number for an average first-year student of their gender at their school. In both the fall and the spring surveys, participants reported how many times in the past month they themselves had consumed five or more drinks in one sitting. Cox and colleagues used linear regression models to examine how perceptions of peer drinking frequency predicted current heavy drinking.1

What did they find?

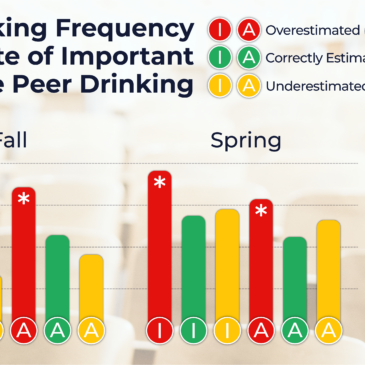

When estimating the heavy drinking frequency of peers important to them, 42% estimated accurately, 37% overestimated, and 21% underestimated. When estimating the heavy drinking frequency of the average first-year peer (determined by averaging the drinking frequencies of all participants), 11% of participants estimated accurately, 85% overestimated, and 4% underestimated. Participants who overestimated the heavy drinking frequency of an average peer reported significantly more frequent heavy drinking overall in the fall and spring of their first year than those who correctly estimated or underestimated. Participants who overestimated heavy drinking frequency of important peers also reported significantly more frequent heavy drinking than those who correctly estimated or underestimated. Participants who overestimated important peer drinking tended to engage in the most heavy drinking (see figure).

Figure. Left: The average number of heavy drinking days reported by those who overestimated, correctly estimated, and underestimated their important peers’ heavy drinking (“I”) and their average peer’s (“A”) heavy drinking, first for the fall semester and then for the spring semester. Asterisks denote significant differences in number of heavy drinking days reported. Right: The sample divided by those who correctly or incorrectly estimated important and average peers’ heavy drinking frequency. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These results provide evidence that overestimating how much fellow college students drink is associated with more frequent heavy drinking, especially when comparing oneself to close peers, and that this overestimation is quite common in first-year students. These results support the role of social imitation in college drinking culture. Intervention efforts can help students showing signs of risky drinking to understand how much their peers drink in reality, and future research could focus on how perceptions of peer drinking change throughout college.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The study sampled students from only one school in the U.S. living on campus, so results might not apply to students outside of this demographic. To assess heavy drinking, the researchers used a five-drink threshold, likely undercounting female heavy drinkers who only need four drinks in one occasion to qualify for binge drinking. Lastly, friendships change in college. Important peers nominated in the fall might be less important to participants in the spring, causing less accurate perceptions of heavy drinking in the spring than in the fall.

For more information:

The National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Jamie Juviler

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

1. Cox and colleagues controlled for demographic factors (age, race, gender, and ethnicity) as well as membership on a varsity sports team, financial aid status, and first-generation student status.