The path to smoking cessation can take many different forms for different people. The research, however, tends to focus on only one outcome: complete cessation. This is at the expense of other intermediate outcomes, such as short-term abstinence and smoking reduction. Understanding these other outcomes is useful, as it provides a more nuanced and realistic view on how people actually work to quit smoking. Today’s ASHES reviews a study exploring the effects of various physical and cognitive factors on three different cessation-related outcomes (Schuck, Otten, Engels & Kleinjan, 2011)

Methods

- Eight hundred and fifty (850) Dutch adolescent smokers enrolled in a larger longitudinal study completed a questionnaire including five smoking-related scales.

- Physical dependence: participants completed the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire, and four items assessing craving intensity.

- Attitudes towards smoking: participants indicated how strongly they agreed with 10 pros and 14 cons about smoking.

- Perceived social approval: participants indicated how strongly they believe their father, their mother, and their best friend feel they should quit smoking.

- Self-Efficacy: participants answered eight items assessing the difficulty they believe they would experience when trying not to smoke in specific tempting situations.

- Smoking behavior: participants answered questions assessing smoking frequency and quit attempts within the last 12 months. If participants indicated a quit attempt, researchers followed up by asking about the length of abstinence.

- Participants completed a follow-up survey containing the same questions one year after baseline.

- Researchers examined responses with respect to three outcome measures derived from the baseline and follow-up smoking behavior questions: short-term (24-hour) abstinence, reduction in smoking behavior, and prolonged (greater than one month) cessation.

Results

- Short-term abstinence (24 hours).

- Participants who perceived less social approval, endorsed more pros of quitting, and reported stronger physical dependence were more likely to report quitting for at least a 24-hour period.

- Smoking reduction.

- Researchers found a significant interaction between craving and social approval. For participants with high craving, low social approval was associated with greater likelihood of reduction in smoking. Those with lower craving showed no effect of social approval on smoking reduction.

- Prolonged cessation (at least one month).

- Participants reporting stronger cravings were significantly less likely to achieve prolonged cessation. Researchers also found a significant interaction term between self-efficacy and physical dependence. Those with greater physical dependence and lower self-efficacy were less successful at achieving prolonged cessation. Those with low physical dependence showed no effect of self-efficacy on cessation.

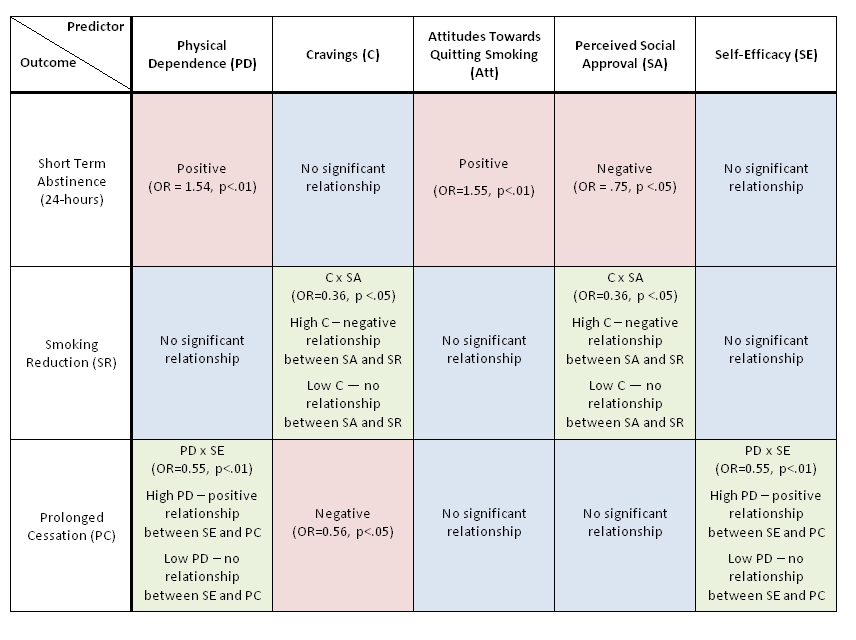

Figure. Summary of associations between predictors on outcomes. Click image to enlarge.

Note. Blue shading indicates no significant relationship between predictor and outcome; pink shading indicates a significant relationship (p < .05) between predictor and outcome; green shading indicates a significant interaction (p < .05) between two predictors. OR = Odds Ratio.

Limitations

- The study relies entirely on self-report data and retrospective recall, potentially leading to inaccurate reporting.

- The questionnaires only ask for cigarette consumption across one specified time period (past 12 months). This cannot show trends in cigarette use.

Discussion

The results show that different factors successfully predicted different smoking cessation-related outcomes. Smoking-related cognitions (e.g., social approval, pros vs. cons of quitting etc.) are useful in predicting short-term abstinence, but physical symptoms (e.g., craving) were more useful for smoking reduction and long-term cessation. The authors hypothesize that this is because cognitions are closely linked to motivation to change behavior, allowing smokers to overcome a short period of abstinence. As the period of abstinence grows longer, physical influences become more important, and become more predictive of long-term success. Studies like this are useful for looking at how various predictors influence different components of quit behavior, instead of looking at only one outcome. This can be used in the future to develop better and more tailored interventions for smokers.

–Daniel Tao

References

Schuck, K., Otten, R., Engles, R.C., Kleinjan, M. (2011). The relative role of nicotine dependence and smoking-related cognitions in adolescents’ process of smoking cessation. Psychology and Health, 26(10): 1310-1326.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.