Research suggests that cigar smoking is on the rise, and that smoking cessation programs rarely address cigar use (Symm et al. 2005). Although, both cigarette smokers and cigar users are at an increased risk of several medical conditions (e.g., lung cancer and coronary heart disease) (Ringel, Wasserman, & Andreyeva, 2005), many people still believe that cigar smoking is a safe alternative to cigarettes. Compared to non-cigar smokers, cigar smokers are more likely to believe cigars are less dangerous than cigarettes (Symm, Morgan, Blackshear, & Tinsley, 2005). Adolescents particularly might be susceptible to thinking that cigars are safe because, as ASHES previously reported, some research suggests that more teens smoke cigars than adults. This week’s ASHES takes another look at adolescent cigar smoking and more specifically, public policy’s influence on current adolescent cigar use (Ringel, Wasserman, & Andreyeva, 2005).

The National Youth Tobacco Survey indicated that 20% of the participants reported cigar use in the past month. Using the 1999 and 2000 waves of this survey, Ringel and colleagues analyzed data from 33,632 adolescent participants aged nine to seventeen. The majority of the participants were White (64.7%). The rest of the participants were African American (17.6%), Hispanic (11.7%), or another race (6%). The same number of males and females participated in the survey. The investigators conducted logistic regression analyses to examine whether increased cigar prices and state tobacco control policies related to cigar use. In addition, the researchers calculated the “price participation elasticity”, which they defined as the percentage change in cigar smoking that would result from a 1% change in price of cigars.

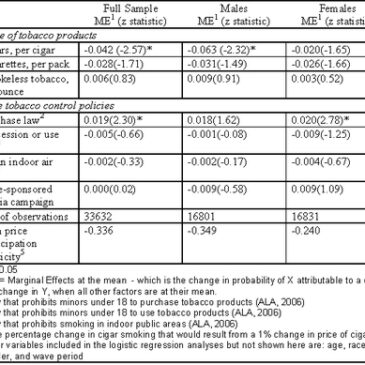

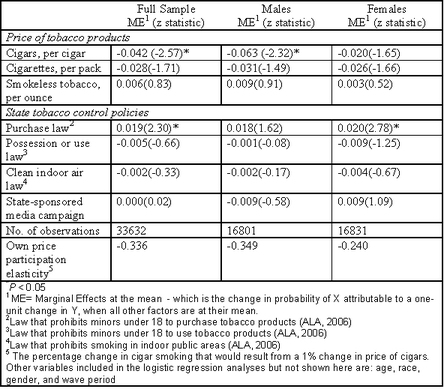

Figure. Logistic Regression Models of the Probability of Current Cigar Use in Adolescents: Data From The National Youth Tobacco Survey (1999-2000). Adapted from Ringel et. al (2005). Click image to enlarge.

Table 1 shows that increased cigar prices significantly decreased the probability of male adolescent cigar use, but not female adolescent cigar use. However, the price effect was not apparent for cigarette and smokeless tobacco use. The results showed that state tobacco control policies (e.g., the clean indoor air law, possession or use law, and state-sponsored media campaigns) did not affect teen cigar use. However, the presence of a Purchase law significantly increased the probability of cigar use among female adolescents, but not males. The study’s findings also found the participation price elasticity to be -0.336. Thus, a 10% increase in cigar prices would reduce the sample’s cigar use by 3.4%.

This study has several limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional; thus, the researchers were unable to examine if increased cigar prices are effective in reducing adolescent cigar use over the long term. Another limitation is that the study did not examine other factors, like peer influences, that might mediate cigar use and or explain the existence of gender differences. Also, the study only assessed the presence of state tobacco control policies and did not measure students’ exposure to or awareness of these policies. This is an important matter to consider because students who were exposed to media campaigns might differ in their cigar use compared to students who were not exposed, despite living in the same jurisdiction.

Increasing cigar prices can deter male adolescents from cigar smoking, but media campaigns seem not to have much influence on adolescent cigar use. Further research should explore issues surrounding price sensitivity and cigar use, as well as examine gender differences and other group differences. More comprehensive research about adolescent cigar use is necessary to determine risk factors of cigar use and effective prevention strategies. Researchers also should study other forms of tobacco use (e.g., cigarettes, pipe, hookah, etc.) in addition to cigars to determine if there are differences in how public policies impact these various tobacco forms. Furthermore, smoking cessation programs should integrate these findings into their services.

–Sarbani Hazra.

References

ALA. (2006). State Legislated Action on Tobacco Issues. Retrieved September 27, 2006, from

http://slati.lungusa.org/StateLegislateAction.asp

Ringel, J. S., Wasserman, J., & Andreyeva, T. (2005). Effects of Public Policy on Adolescents’ Cigar Use: Evidence From the National Youth Tobacco Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 95(6), 995-998.

Symm, B., Morgan, M. V., Blackshear, Y., & Tinsley, S. (2005). Cigar smoking: An ignored public health threat. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(4), 363-375.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.