Anti-marijuana advocates have used a number of different types of mass media campaigns intended to reduce the use of marijuana (Schilling & McAlister, 1990). For example, the Sensation Seeking Targeting (SENTAR) prevention approach to reducing use of illicit substances rests on the premise that sensation seeking is a potent risk factor for marijuana use. Accordingly, SENTAR’s style of media campaign crafts messages for television ads using a fast-paced, unconventional, and suspenseful approach considered to appeal particularly to sensation seekers. The ads used teen actors to depict several negative consequences of marijuana use (e.g., impaired judgment, effects on relationships, loss of motivation or coordination, lung damage). This week, STASH reviews a study that examines the impact of three SENTAR-based anti-marijuana television campaigns on 30-day marijuana use among adolescents who had high scores on a measure of sensation seeking (Palmgreen, Donohew, Lorch, Hoyle, & Stephenson, 2001).

Palmgreen et al. conducted a 32-month interrupted time-series study of marijuana use among teens attending public school in Fayette County (Lexington), Kentucky and Knox County (Knoxville), Tennessee. SENTAR-based anti-marijuana television campaigns were aired initially in Fayette County during January through April 1997 (campaign 1) and in both counties during January through April 1998 (campaign 2). One hundred teens (grades 7-10) randomly selected from each county participated in monthly self-administered interviews via laptop computer before, during and after the ad campaigns. The response rate was 63% in Fayette County (i.e., number of completions divided by the sum of completions and refusals). Questions assessed exposure to the anti-marijuana ads under study, marijuana use over the last 30 days, attitudes toward marijuana use and other substances, and various risk and protective factors including sensation seeking behavior. Levels of marijuana use in the past 30-days in the sample were consistent with national norms reported in the University of Michigan’s Monitoring the Future Study in 1997 and 1998 (i.e., approximately 23% for 12th graders) (Institute for Social Research University of Michigan).

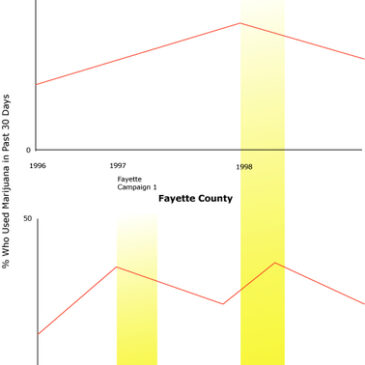

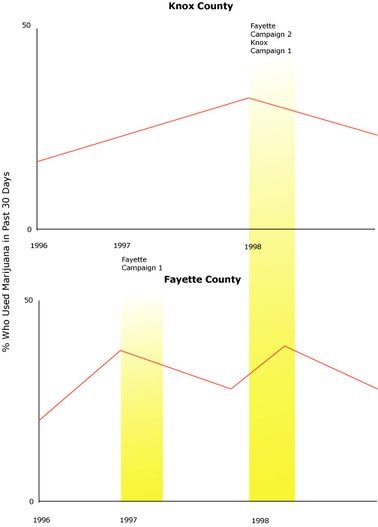

The researchers examined whether there was a relationship between sensation seeking and responses to the media campaigns after adjusting for 12 risk and protective factors associated with marijuana use (e.g., perceived peer drug use, deviance, availability of drugs, grade point average) (Newcomb & Felix-Ortiz, 1992). Respondents with sensation seeking scores higher and lower than the full sample median were analyzed separately. Analyses of low sensation seekers found low levels of 30-day marijuana use, no developmental trend for marijuana use, and no campaign effects for either county during either campaign time period. High sensation seekers in Knox County had significant changes in marijuana use after adjusting for the other risk and protective factors (P<.001; adjusted R2 = .442, with very low autocorrelation p = .032). As shown in Figure 1, this group showed a significant upward trend reflecting increasing 30day marijuana use preceding the campaign from May 1996 to December 1997 (P <.001) and a significant downward change immediately after the start of the campaign in January 1998 and continuing until December 1998, the end of data collection (P = .001). High sensation seekers in Fayette County also had significant changes in marijuana use after adjusting for the other risk and protective factors (P<.007; adjusted R2 = .351, with acceptable autocorrelation, p = -.243). As shown in Figure 1, this group showed a significant downward change at the start of campaign 1 January 1997 (P = .002), but the effects of campaign 1 appeared to wear off after approximately 6 months. There was a significant upward wear-off trend from November 1997 to February 1998 (P =.003) and a significant downward trend from March to December 1998 after the initiation of campaign 2 (P = .002).

Figure. Knox County and Fayette County 30-day marijuana use regression plots for adolescents who had high scores on a sensation seeking measure. (Figure adapted from Palmgreen, et al, 2001) Click image to enlarge.

This study has some limitations. The study sample only consists of teens attending public school; a parent or guardian gave informed consent for the teen to participate. Therefore, the sample might not be representative of all teens in Fayette and Knox counties. For example, delinquent teens who were not attending school during the data collection period might be more likely to engage in substance using behaviors. Also, self-reported substance use might under or over report actual use. In addition, there are other factors that could influence marijuana use among the targeted population (e.g., parental influence or exposure to other public health interventions) that are not assessed for this study and might have contributed to changes in marijuana use.

Despite these concerns, the results from this study suggest that public health campaigns can significantly decrease marijuana use for a targeted population. However, there is no explanation for why the effect of the first campaign seemed to “wear off” after the campaign was over but the second campaign seemed to initiate new changes for the Fayette sample. The Knox sample only received the first campaign, so this effect could not be examined for that population. Further exploration of this pattern could determine whether repeating the intervention helped to reinforce better behaviors among the same group of teens or captured more attention among different groups of teens. The authors acknowledge that use of mass media strategies alone is not sufficient to address public health issues such as substance use. Use of other interventions (e.g., group or individual counseling, legal sanctions) in combination with mass media strategies may be necessary to comprehensively address marijuana use among teens.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Allyson Peller.

References

Institute for Social Research University of Michigan. Monitoring the Future. Retrieved April 24, 2006, from http://www. monitoringthefuture.org/

Newcomb, M., & Felix-Ortiz, M. (1992). Multiple Protective and Risk Factors for Drug Use and Abuse: Cross-Sectional and Prospective Findings. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 63(2), 280-296.

Palmgreen, P., Donohew, L., Lorch, E. P., Hoyle, R. H., & Stephenson, M. T. (2001). Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: tests of sensation seeking targeting. Am J Public Health, 91(2), 292-296.

Schilling, R. F., & McAlister, A. L. (1990). Preventing drug use in adolescents through media interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol, 58(4), 416-424.