Studies show that young people enjoy gambling. Between 70% and 90% of youths currently in school gamble; further, between 15% and 40% of them gamble regularly (Poulin, 2000; Shaffer & Hall, 1996; Vitaro, Ladouceur, & Bujold, 1996). It is necessary to find ways to prevent students from becoming excessive gamblers. In addition, it is very important to identify interventions that will limit young people who already gamble from developing the negative consequences associated with pathological gambling. Researchers previously have examined the effect of educational videos on viewers’ attitudes and knowledge about substance-related problems. LaPlante, Kidman, Donato, LaBrie, Shaffer, & Blake (2003) conducted a study determining how effective a video called Alcohol: True Stories was in stimulating changes in alcohol-related attitudes in comparison to a traditional alcohol education lecture. They found that for junior high students, the video was more effective than a lecture at changing attitudes. This week, the WAGER reviews a recent study by Ladouceur, Ferland, Vitaro, and Pelletier (2005) that examined the effectiveness of a video created to educate adolescents about pathological gambling and its possible consequences. This intervention attempted to correct young people’s distorted perceptions about gambling and to increase their awareness about excessive problem gambling among youths.

Five hundred sixty eight grade 11 and 12 Québecois students from three high schools participated in this study. The schools were randomized into two groups: an experimental group and a control group. Both groups met twice with the research assistant. The experimental group of 361 students completed a questionnaire and then watched a 20-minute video called Gambling Stories. In the video, three people in a bar described the development of their gambling behavior and the consequences of that behavior. The video aimed to clarify the meaning of chance, as well as to teach teenagers how to more accurately assess the symptoms of losing control of one’s gambling habits. A month later the experimental group completed the second questionnaire. The 207 students in the control group completed the same two questionnaires with the same month inter-survey interval, but did not watch the video. The questionnaires included 32 items that evaluated the students’ knowledge about gambling (both recreational and excessive) and their stereotypical perceptions about excessive gamblers.

The authors used ANCOVAs (analyses of covariate variance) to examine the effects of watching the video on the students’ knowledge and stereotypes. They controlled for age and gender in each of their analyses because the experimental and control groups differed at baseline on these variables. The interactions between group (i.e., experimental or control) and time (i.e., pre-questionnaire or post-questionnaire) showed that the video significantly increased the students’ overall knowledge about gambling activities and excessive gambling. The video also significantly decreased the students’ level of stereotypical views held about excessive gamblers. Three quarters of the students in the experimental group acknowledged learning new facts and ideas about gambling. Using a chi-square test, the authors reported that significantly fewer teenagers in the experimental group than in the control group wanted to gamble in the forthcoming year.

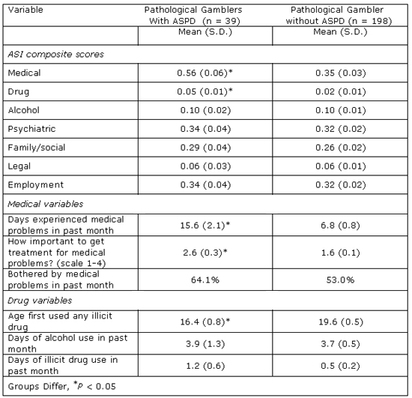

TABLE 1: OUTCOME MEASURES RESULTS OF WATCHING “GAMBLING STORIES” (ADAPTED FROM LADOUCEUR ET AL., 2005)

There are a few limitations to this study. The students were randomized at the level of school, and there were demographic differences between the control and experimental groups. Because the authors do not report whether the groups’ initial perceptions of gambling differed, we cannot be certain that the video is responsible for the observed difference in perception change between the groups, and that this change is not due to the groups’ inherent differences at the start of the study.

Despite these limitations, this study presents a promising approach for intervening with adolescents’ perceptions about gambling. It is possible that adolescents do not view gambling as a potentially dangerous activity and are not concerned about excessive gambling habits. This could be because their image of the pathological gambler does not resonate with their own experience and knowledge. An educational video is one step to help prevent the likelihood of young people becoming pathological gamblers. This kind of intervention has importance as students leave high school and have more opportunities to gamble. By decreasing the stereotypes held about excessive gamblers, the video might have encouraged the adolescents to give more realistic thought to the potential adverse consequences of gambling.

A logical next step would be to conduct follow-up studies to determine whether students’ newfound knowledge and perceptions about gambling, after viewing the video, endured. It also will be important to determine whether the change in attitudes influences behavior change. The follow-up studies should examine the extent to which the viewers’ modified attitudes paralleled their actual gambling or drinking behavior.

What do you think? Comments on this article can be addressed to Audrey Bree Tse.

References

Ladouceur, R., Ferland, F., Vitaro, F., & Pelletier, O. (2005). Modifying youths’ perception toward pathological gamblers. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 351-354.

LaPlante, D. A., Kidman, R. C., Donato, A. N., LaBrie, R. A., Shaffer, H. J., & Blake, J. (2003). Evaluating the promise of Alcohol: True Stories. Boston, MA: Harvard Medical School Division on Addictions & Family Health Productions.

Poulin, C. (2000). Problem gambling among adolescent students in the Atlantic provinces of Canada. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(1), 53-78.

Shaffer, H. J., & Hall, M. N. (1996). Estimating the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorders: A quantitative synthesis and guide toward standard gambling nomenclatures. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 193-214.

Vitaro, F., Ladouceur, R., & Bujold, A. (1996). Predictive and concurrent correlates of gambling in early adolescent boys. Journal of Early Adolescence, 16(2), 211-228.