Addiction substitution happens when someone in recovery from one substance or behavior turns to another—for example, smoking more cigarettes after cutting back on drinking. This can be explained by the Syndrome Model of Addiction, which argues that all addictions share similar underlying vulnerabilities, such as depression or anxiety. If these underlying risks aren’t addressed, a person may turn to another addictive behavior to cope. This week, as part of our Special Series in Honor of Dr. Howard Shaffer, ASHES reviews a study by Christina S. Lee and colleagues that examined the prevalence of and characteristics associated with substitution behaviors (defined as the increased use of other substances) among a sample of U.S. adults attempting to reduce their alcohol use.

What were the research questions?

How prevalent is addiction substitution among a sample of U.S. adults attempting to reduce their alcohol use? Do people who engage in substitution differ from those who don’t?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 319 U.S. online survey workers (age 18 and older) in July 2020. All participants had used alcohol in the past week. They reported their alcohol use, other substance use, and psychological distress. Participants also indicated whether they had tried to reduce their drinking in the past three months, and if so, whether they had increased their use of four substances (sweet snacks, salty snacks, nicotine, and cannabis). Those who had increased their use of one or more substances were defined as “substituters”. The researchers used descriptive statistics to determine the prevalence of substitution and compare the characteristics of substituters to non-substituters.

What did they find?

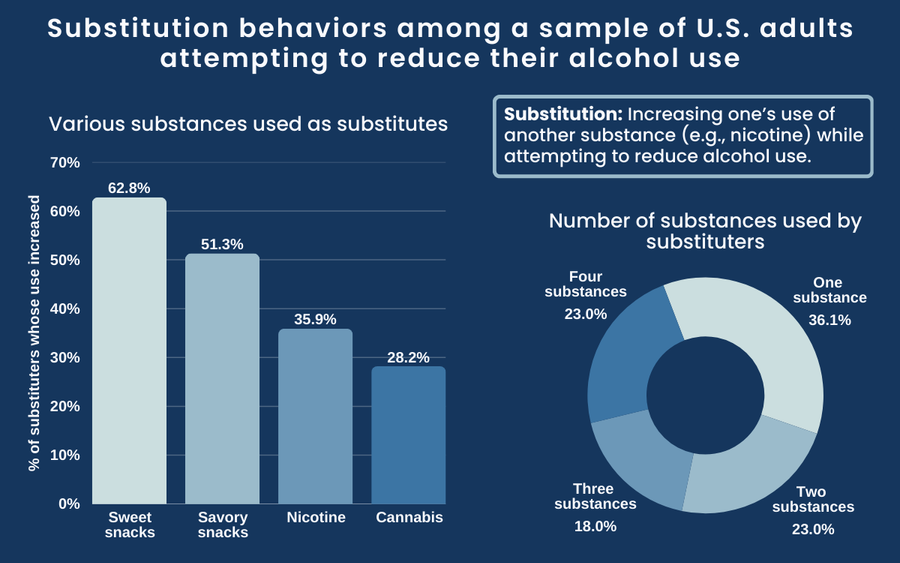

One-quarter of participants (n = 78) had recently tried to cut down or stop drinking. Of these, 78.2% (n = 61) had increased their use of another substance while doing so. Sweet snacks and savory snacks were the most commonly substituted substances, followed by nicotine and cannabis (see Figure). Most participants increased their use of more than one of these substances. In terms of distinguishing characteristics, substituters reported using illicit drugs (e.g., heroin), while non-substituters did not. Both groups used nicotine, but cigarette smoking and vaping were more common among substituters—for example, 52.5% reported vaping compared with 16.7% of non-substituters. Substituters also reported higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

Figure. Substitution behaviors among a sample of U.S. adults attempting to reduce their alcohol use. Left: percent of substituters who increased their use of each substance while reducing drinking. Right: distribution of the number of substances whose use increased, by percent of substituters. Note: This study only examined substitution related to these four substances. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings suggest that substitution is common among people reducing their drinking. Substitution can affect recovery by elevating the risk of resuming substance use or contributing to the development of a new addiction. Addiction providers should be aware of these risks and proactively educate their clients on strategies to avoid substitution—especially with nicotine. The results also underscore the importance of screening for co-occurring mental health disorders in treatment settings, and the need for integrated treatment approaches that address underlying disorders concurrently.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Data were from a community (non-clinical) sample and participants were not asked whether they had sought treatment for their alcohol use. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to people who are actively seeking treatment. The data were cross-sectional, so we cannot determine the causal relationship between substitution and substance use and psychological distress. This study focused on alcohol as the primary initial substance; more research is needed to see whether these findings occur among people trying to quit or cut back on other substances, like nicotine.

For more information:

SmokeFree offers tools and tips for quitting and maintaining abstinence from tobacco use. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also provides research and tips about smoking and how to quit. For additional self-help tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Kira Landauer, MPH

Want CE credit for reading BASIS articles? Click here to visit our Courses Website and access our free online courses.