Gambling Disorder is a condition with a number of known risk factors, including early exposure to gambling. The convergence between gaming and gambling might expose more young people to gambling. For example, loot boxes in video games are virtual items that can be bought with real money and have varying chances of producing in-game items, making them similar to gambling. Recent research has drawn links between spending on loot boxes and problem gambling, which suggests that buying loot boxes might encourage people to gamble at dangerous levels. But are participants really reporting that they buy loot boxes and experience harm from traditional gambling, or do they consider loot boxes to be just another kind of gambling? This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Leon Xiao and colleagues that explored whether pre-screening for and defining gambling reduces the strength of the relationship between loot box spending and problem gambling.

What were the research questions?

(1) Is there a relationship between loot box spending and problem gambling? (2) Does this relationship change if what constitutes gambling is clearly defined, and participants are pre-screened for gambling involvement before answering questions about problem gambling?

What did the researchers do?

The research team recruited a sample of video game players via the survey sampling company, Prolific, and then randomly assigned participants to either a pre-screening condition (n = 1,022) or a non-screening condition (n = 1,005).

- Participants in the screening group answered an initial item that inquired about gambling in the past 12 months. As part of this question, they were given a list of activities defined as “gambling,” which did not include purchasing loot boxes. Participants who endorsed past-year gambling then completed the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI), which asks questions like, “Has gambling caused you any health problems, including stress or anxiety?” and “Have you felt you might have a problem with gambling?” The researchers used PGSI scores to classify participants as “non-problem gambling,” “low-risk gambling,” “moderate-risk gambling,” or “problem gambling.”

- Participants in the non-screening condition went straight to the PGSI without being asked about their gambling involvement.

Both sets of participants also answered a question regarding their loot box spending, as well as an open response item where participants were able to provide more information or feedback about their gambling behaviors or perspectives on the study design.

What did they find?

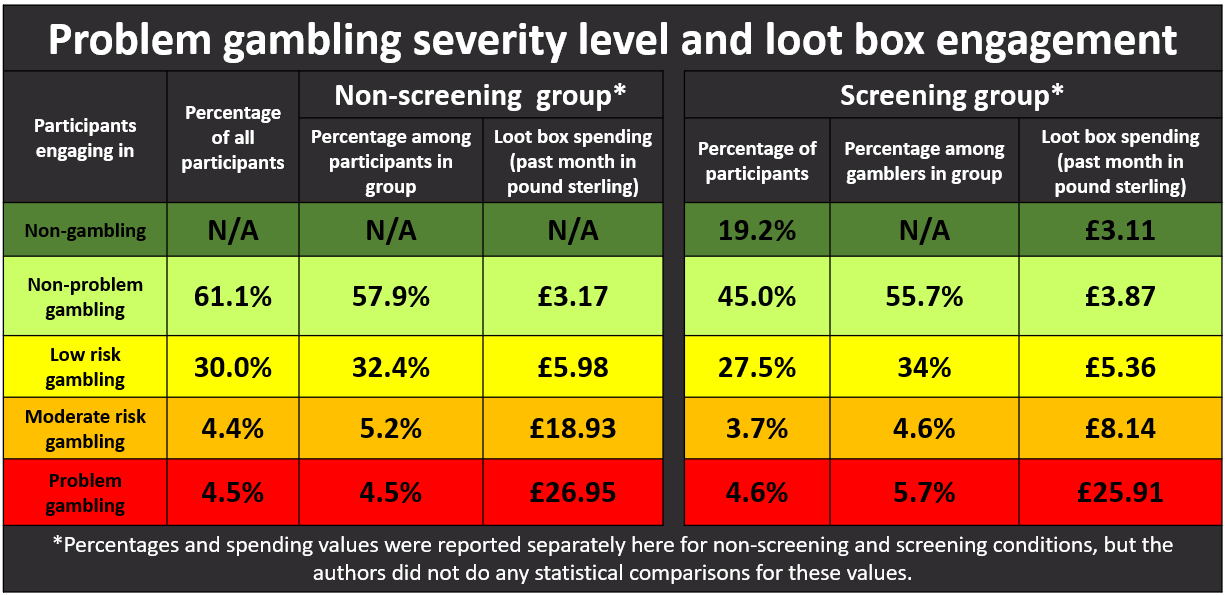

Of participants in the screening group, 80.9% reported gambling in the past 12 months. Of these, 5.7% experienced problem gambling according to the PGSI. In both groups, those with more loot box spending had higher PGSI scores (see Figure). Interestingly, however, participants in the non-screening condition scored higher on the PGSI, which suggests that some participants in the non-screening condition may have been considering harms experienced from loot boxes when completing the PGSI. Finally, participants used the open response items to mention that they thought about other gambling-like behaviors, such as cryptocurrency trading, when answering the PGSI questions.

Figure. The sample size was n = 1,005 for the non-screening group and n = 1,022 for the screening group. Figure shows the percentage of participants at each level of problem gambling and their average loot box expenditure in GBP (i.e., British Pounds; £) by condition. Data in the screening group is limited to participants who reported gambling in the past 12 months. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These results indicate that there is ambiguity in gambling harm measures. Participants who did not complete the pre-screen might have used a broader definition of gambling, one that included buying loot boxes. This would increase the prevalence of gambling harms because the inclusion of loot boxes and other “gamblified” activities allows for a greater range of harms. Furthermore, previous research has shown that some of these activities are especially problematic due to a lack of regulations as they often operate in legal gray areas. As gaming and gambling continue to converge, it would be helpful for researchers, policy makers, healthcare professionals, and the general public to develop a shared understanding of what constitutes gambling.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

Because this study specifically focused on loot box engagement as gambling, it cannot provide insights into other behaviors that participants may be factoring in when completing gambling screens. More specifically, though the screening methodology clearly defined the behaviors that constitute gambling, participants in the non-screening condition might have also included other non-loot box behaviors they believed constituted gambling, such as cryptocurrency trading. An additional limitation is that the sample was older than previous studies on loot box engagement, and primarily consisted of white participants which might limit the generalizability of the findings.

For more information:

Individuals who are struggling with problem gambling may find support at Mass.gov or the website for The National Council for Problem Gambling. Others who are concerned about their video game involvement may learn more about video game addiction via the Cleveland Clinic. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

—John Slabczynski

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.