Public perception of addiction – whether substance or behavior based – is integral in the creation of public policy. This is reflected in the United States’ Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, which encompassed prevention, treatment, recovery, criminal justice reform, and more of an effort to fight the opioid epidemic. However, global public policies tend to focus more on substance addictions rather than behavioral. This is true in the United Kingdom, even as both gaming and gambling have become more commonplace and more problematic. In this week’s WAGER, we reviewed a study by Seth Jamieson and Chris Dowrick that investigated the public perception of substance and behavioral addictions in the UK.

What were the research questions?

How does the British public perceive substance addictions and behavioral addictions based on a symptom pattern? Are substance addictions more commonly recognized than behavioral addictions?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited participants via Facebook and Reddit through the lead author’s profiles on those platforms. They asked recruited participants to recruit additional participants (i.e., a snowball sample). Participants chose one of four colors, and that’s how they were assigned to a substance or behavior category: gaming, gambling, alcohol, or cocaine. They read a series of vignettes for that substance/behavior. Each vignette portrayed a character either not showing, somewhat showing, or clearly showing one of the six ICD-10 characteristics of dependence1, for a total of 18 vignettes. For instance, in the gaming condition, one character shows no signs of withdrawal when he stops playing, another shows some signs of withdrawal, and a third character shows severe signs of withdrawal. Following each vignette, participants were shown the statement, “[Name in vignette] is addicted to [substance/activity]” and used a Likert Scale with five options that ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to indicate how much they agreed. The researchers coded the response categories from -2 (“strongly disagree”) to 2 (“strongly agree”) and combined the six responses per symptom severity (e.g., collapsed across all six “clearly showing the symptom” responses). Then they used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to compare the medians (and their distributions) for the questions for each substance and activity and for each symptom severity.2

What did they find?

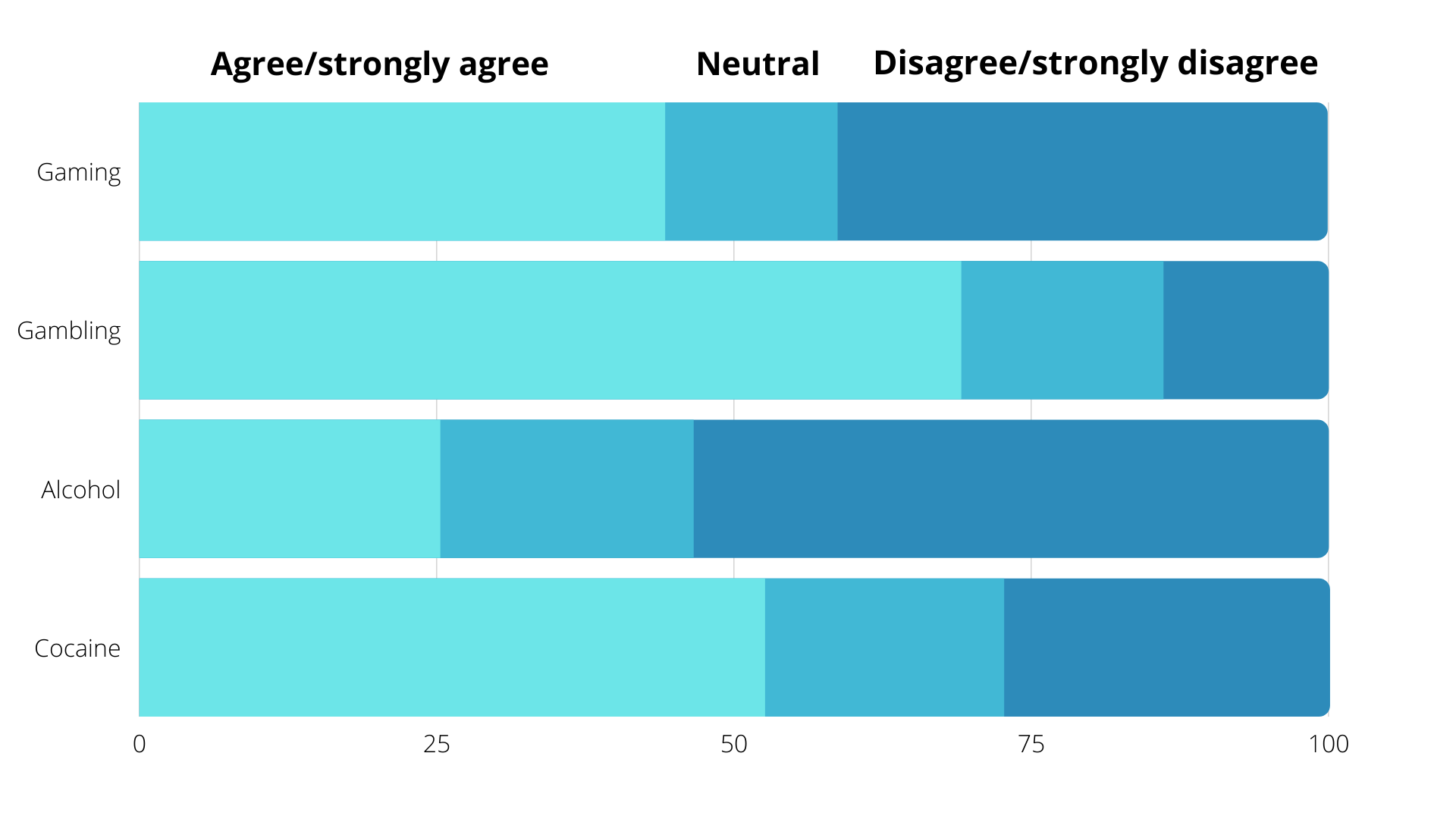

When the characters did not show or only somewhat showed an ICD-10 symptom, participants (rightly) tended not to see them as addicted. However, this was more true for gaming, alcohol, and cocaine addiction than for gambling; fully 69.1% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the characters were addicted to gambling even when they only somewhat showed the ICD-10 symptom (see Figure), and 20.4% did so when they didn’t show the symptom at all. On the other hand, when the characters somewhat showed or clearly showed an ICD-10 symptom, participants were least likely to agree that they were addicted when in the alcohol category (see Figure). Gaming and cocaine were at an intermediate level.

Figure. Percent of participants who agreed/strongly agreed, disagreed/strongly disagreed, or were neutral in response to the statement, “[Name in vignette] is addicted to [substance/activity]”. Data show responses when the characters in the vignettes somewhat showed an ICD-10 addiction symptom (e.g., compulsion, control, withdrawal). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The findings mean that the perception of gambling being the “hidden addiction” is wrong – at least, it is in the UK based on the results from this study. One can only hope that the awareness of the symptoms of gambling addiction will reduce stigma towards those suffering with addiction, leading to more people seeking out and getting help. And, with an increased public awareness of the consequences of problem gambling, more policies can be put into place emphasizing prevention and treatment programs, such as these help resources assembled by the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. Additionally, the findings suggest limited knowledge about some symptoms of addiction. This points to a need for greater education about substance use and behavioral-based addictive disorders, which is a major goal of The BASIS and other organizations, such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

There are two key limitations of this study. First, the study really can’t tell us how accurately participants were perceiving a state of addiction because they had incomplete clinical pictures in the vignettes (i.e., only one symptom was portrayed at a time). Second, the sample only included people who have internet access and a social media profile, so they might not generalize to high-risk populations such as the unhoused or individuals who are institutionalized.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a gambling problem? Visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for screening tools and resources. For additional resources, including gambling and self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Karen Amichia

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Compulsion, control, withdrawal, tolerance, neglect of other pleasures/interests, and continued use despite adverse consequences.

[2] None of the characters could be definitively defined as addicted because they would need to display at least 3 of the 6 ICD-10 criteria. However, the researchers explored participants’ perceptions of the severity of addiction based on just one criterion (e.g., withdrawal) per character.