People who use illicit drugs (PWUD) are likely to experience or witness a drug overdose event but report hesitancy in involving emergency services for fear of legal repercussions. Drug-related Good Samaritan laws provide immunities and limited legal protections for individuals who call 911 – for themselves or for someone else – during an overdose event. These laws are intended to encourage calls to emergency services, but little is known about their knowledge among PWUD. This week, STASH reviews a study by Soroush Moallef and colleagues that evaluated the prevalence of and factors associated with accurate Good Samaritan law knowledge among PWUD in Vancouver, British Columbia.

What were the research questions?

What is the prevalence of accurate Good Samaritan law knowledge among people who use drugs? What individual and social-structural environmental factors are associated with accurate Good Samaritan law knowledge among people who use drugs?

What did the researchers do?

Canada enacted the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act (GSA) in 2017.1 The following year, Moallef and colleagues administered a questionnaire assessing GSA knowledge to PWUD participating in three ongoing prospective cohort studies in Vancouver, British Columbia. The questionnaire was completed by 1,258 PWUD. Participants were asked:

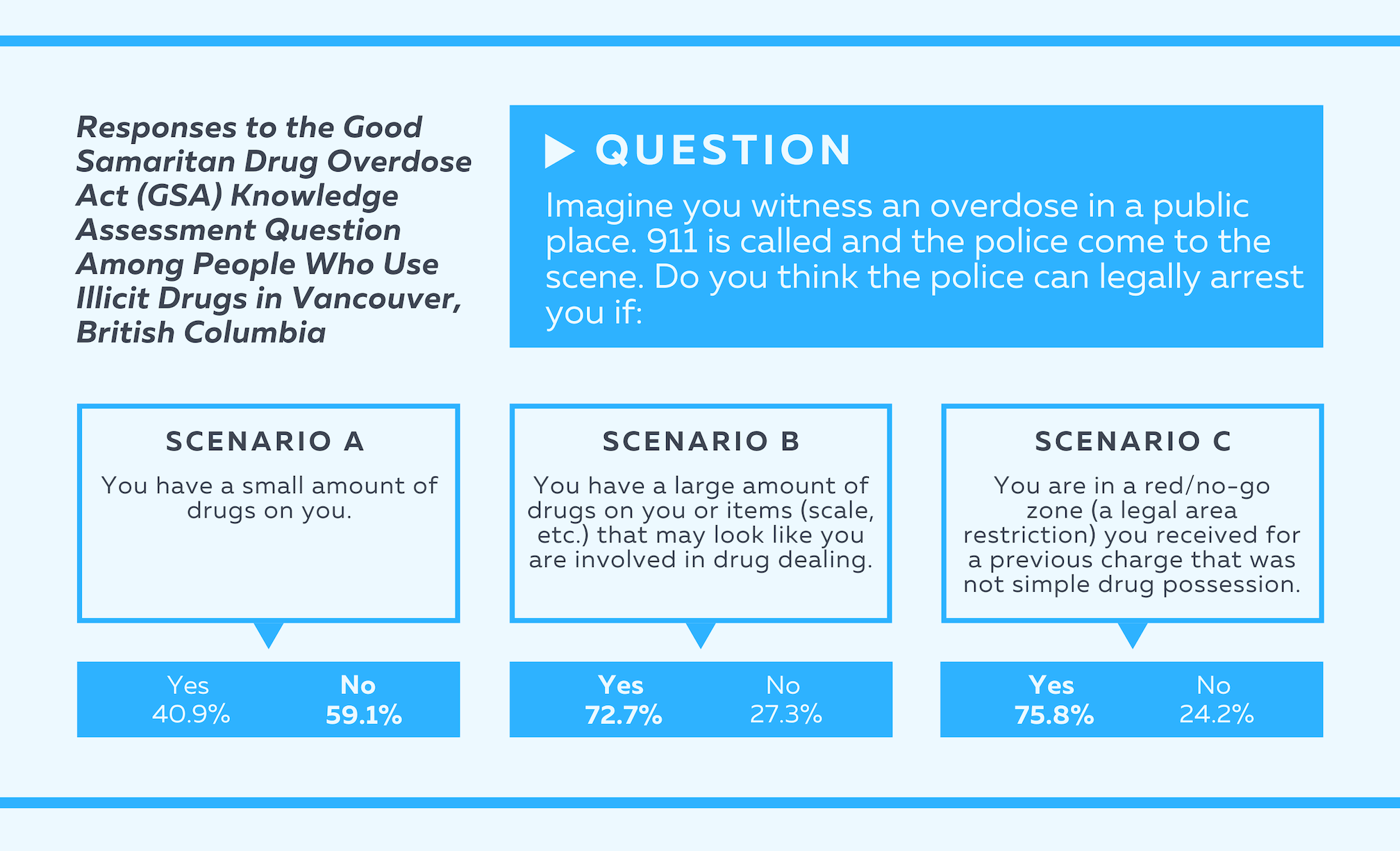

“Imagine you witness an overdose in a public place. 911 is called and the police come to the scene. Do you think the police can legally arrest you if: you have a small amount of drugs on you (Scenario A), you have a larger amount of drugs on you or items (scale, etc.) that may look like you are involved in drug dealing (Scenario B), and you are in a red/no-go zone (a legal area restriction) you received for a previous charge that was not simple drug possession (Scenario C).”

Moallef and colleagues categorized participants as having accurate GSA knowledge if they correctly identified Scenario A as the only scenario where the police could not legally arrest them. The researchers also measured the prevalence of underestimated GSA protections (i.e., belief that the police could legally arrest the individual in all scenarios) and overestimated GSA protections (i.e., belief that the police could not legally arrest the individual in all scenarios or a combination of scenarios). Moallef and colleagues also measured individual and social-structural environmental variables, such as experiencing homelessness and having witnessed an overdose event. They used bivariable and multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with accurate GSA knowledge.

What did they find?

More than half (56.8%) of participants had witnessed an overdose event in the past six months. About one-quarter of participants (28.5%) had accurate knowledge of the GSA, while 37.2% underestimated and 32.6% overestimated GSA protections. Scenario A was answered incorrectly most often, with 40.9% of participants answering incorrectly (see Figure). Accurate knowledge of the GSA was especially low among individuals who had witnessed an overdose event (29.7%), experienced homelessness (30.7%), and lived in single-room occupancy accommodations (28.3%) in the past six months. Participants who reported involvement in drug dealing were more likely to have accurate knowledge of the GSA, and individuals who reported ever having a negative police encounter were less likely to have accurate knowledge of the GSA.

Figure. Responses to the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act (GSA) knowledge assessment question among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, British Columbia. Numerical values indicate the percentage of respondents who answered yes and no for each scenario. Bolded values indicate correct responses. Adapted from Moallef et al., 2021. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Accurate Good Samaritan law knowledge is associated with an increased likelihood of calling emergency services during an overdose event. This study found that three-quarters of PWUD surveyed did not have accurate knowledge of the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act (GSA), which is concerning because more than half of the respondents had witnessed a recent overdose. Additionally, one-third of participants overestimated GSA protections, putting them at risk for legal consequences which might perpetuate fear of emergency service involvement at overdose events. These findings indicate a need for targeted education about Good Samaritan laws for PWUD. Word-of-mouth from other PWUD and news/media have been found to be common means of learning among this population. Understanding of these laws was low among subpopulations of PWUD, such as individuals living in single-room occupancy accommodations where fatal overdoses commonly occur. Good Samaritan-related educational resources and interventions (e.g., tenant-led overdose response programs) should be implemented in these residences.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Findings from this study may not be generalizable to other populations (e.g., non-PWUD) or geographic locations with different Good Samaritan laws (e.g., the United States).

For more information:

A 2021 Government Accountability Office report offers details about Good Samaritan laws in U.S. jurisdictions. Are you worried that you or someone you know has an addiction? The SAMHSA National Helpline is a free treatment and information service available 24/7. For more details about addiction, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Kira Landauer, MPH

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] The GSA provides protections from arrest, charges, or prosecution related to the possession of a controlled substance for personal use (i.e., simple possession) and breach of conditions (e.g., probation orders, parole) regarding simple possession of a controlled substance to individuals seeking emergency support during an overdose event.