Driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs (DUI) remains a leading public health concern despite general declines in the behavior over the past few decades. During 2016, 10,497 people died in alcohol-impaired driving crashes, representing nearly one-third of all traffic-related deaths in the United States. Though many studies have examined the predictors of DUI behavior, few have looked at family and peer factors that influence DUI. This week, The DRAM reviews one of the first longitudinal studies of the effects of peer and family factors on DUI, conducted by William Pelham III and Thomas Dishion.

What was the research question?

How do family and peer environments interact to influence severe DUI behavior?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers analyzed a sample of 999 youth initially recruited from three middle schools in an urban area and followed them for more than 20 years. For this study, they used measures of family relationship quality (i.e., how well family members get along with each other), parental monitoring (i.e., how much parents know about what their children are up to), and associations with prosocial and deviant peers (i.e., whether youth hang out with prosocial or deviant peers and whether they discuss deviant topics with their peers) collected from multiple respondents (i.e., parents, youth, direct observation) when the youth were age 16-17. They tested whether these measures could predict whether participants were arrested for DUI at any time across the 15 years from age 16-17 to age 31-32. They also examined whether one set of measures (i.e., family or peer) was a stronger predictor than the other.

What did they find?

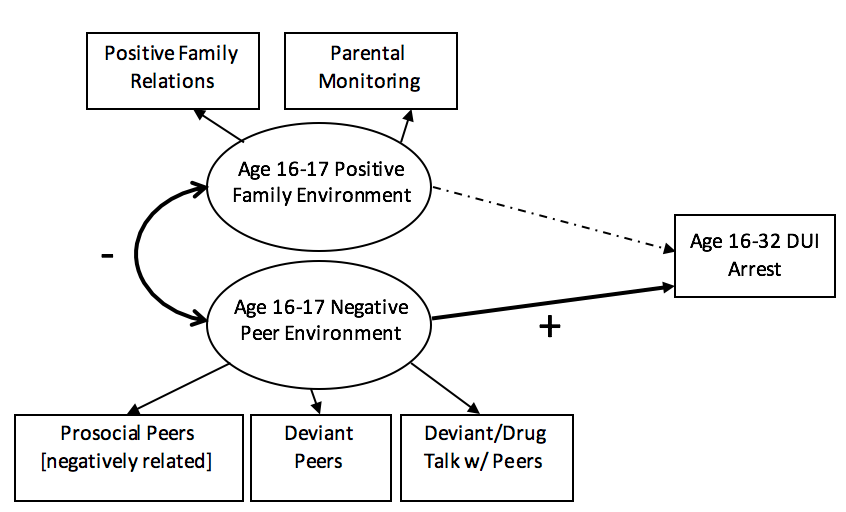

Prosocial peer affiliation, parental monitoring, and deviant peer affiliation each predicted how likely youth were to get arrested for DUI. Youth who engaged with prosocial peers and whose parents monitored their behavior were less likely to be arrested for DUI. Youth who interacted with deviant peers and engaged in deviant talk with those peers were more likely to be arrested for DUI. Family relationship quality appeared protective against DUI, but this relationship did not reach statistical significance. The researchers constructed a model where positive family relations and parental monitoring formed a latent construct called Positive Family Environment, and prosocial peers, deviant peers, deviant talk with peers, and drug talk with peers measured a latent construct called Negative Peer Environment. The researchers tested whether these two latent constructs predicted future DUI arrest. They found that Positive Family Environment and Negative Peer Environment related strongly to each other, but only Negative Peer Environment predicted DUI arrest.

Figure. Relationships among family environment, peer environment, and likelihood of DUI arrest. In this model, the measured variables (e.g., parental monitoring) are represented by rectangles. The latent constructs are represented by ovals. The model then tests the relationships between the two latent constructs and likelihood of Age 16-32 DUI arrest. Note: + indicates a positive relationship; – indicates a negative relationship; the dotted line indicates the relationship was not statistically significant. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These results demonstrate that both family and peer environment contribute to risk for DUI, but at least by high school, interactions with peers, both prosocial and deviant, hold more influence. As previous work has shown, parental monitoring likely influences youths’ peer group choices, which in turn more directly influence DUI. A promising finding is the protective influence of prosocial peers. This suggests that interventions that increase interactions with and the influence of these peers might be able to reduce later DUI behavior.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

This study had missing data for many of the variables used to create the family and peer environment measures. Though the researchers accounted for the missing data using imputation, potential for bias still exists if the data are not missing at random. In addition, the researchers’ models were constrained to the prediction of DUI arrests. It is possible that a different set of variables or interaction would predict DUI behavior. Finally, the study examined parent and peer influences at age 16-17; parent and peer relative influence on behavior changes dramatically from the early teens to the late teens, so a study examining the influence of these groups at earlier ages on later DUI could add meaningful information to our understanding of these associations.

For more information:

If you or a loved one is experiencing problems with alcohol, The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism offers resources for finding and getting help.

— Sarah Nelson

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.