Depression and alcohol-related problems co-occur among college students. This relationship is mediated by drinking-to-cope motives: college students with depression are more likely to use drinking to cope with negative feelings, and this type of drinking is more likely to lead to problems. However, recent research also shows that mindfulness—being actively and openly attentive to the present— can reduce people’s chances of experiencing alcohol-related problems. This week, as part of our Special Series on Mindfulness and Addiction, The DRAM reviews a study by Adrian J. Bravo and his colleagues exploring possible effects of mindfulness on the link between depressive symptoms, drinking-to-cope motives, and alcohol-related problems.

What was the research question?

Is the path from depression to drinking-to-cope motives to alcohol-related problems weakened by mindfulness?

What did the researchers do?

Bravo and his colleagues recruited 699 college students from psychology classes at a large university in the southeastern part of the United States. Participants completed an online survey that included items on trait mindfulness (mindfulness as a natural state, as opposed to mindfulness when doing activities such as meditation), depression symptoms, drinking-to-cope motives, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems. The researchers used structural equation modeling to measure the relationships between depressive symptoms, drinking-to-cope motives, and alcohol-related problems among the 448 respondents who reported drinking during the previous month. They then tested whether these relationships were different for people who scored high or low on mindfulness.

What did they find?

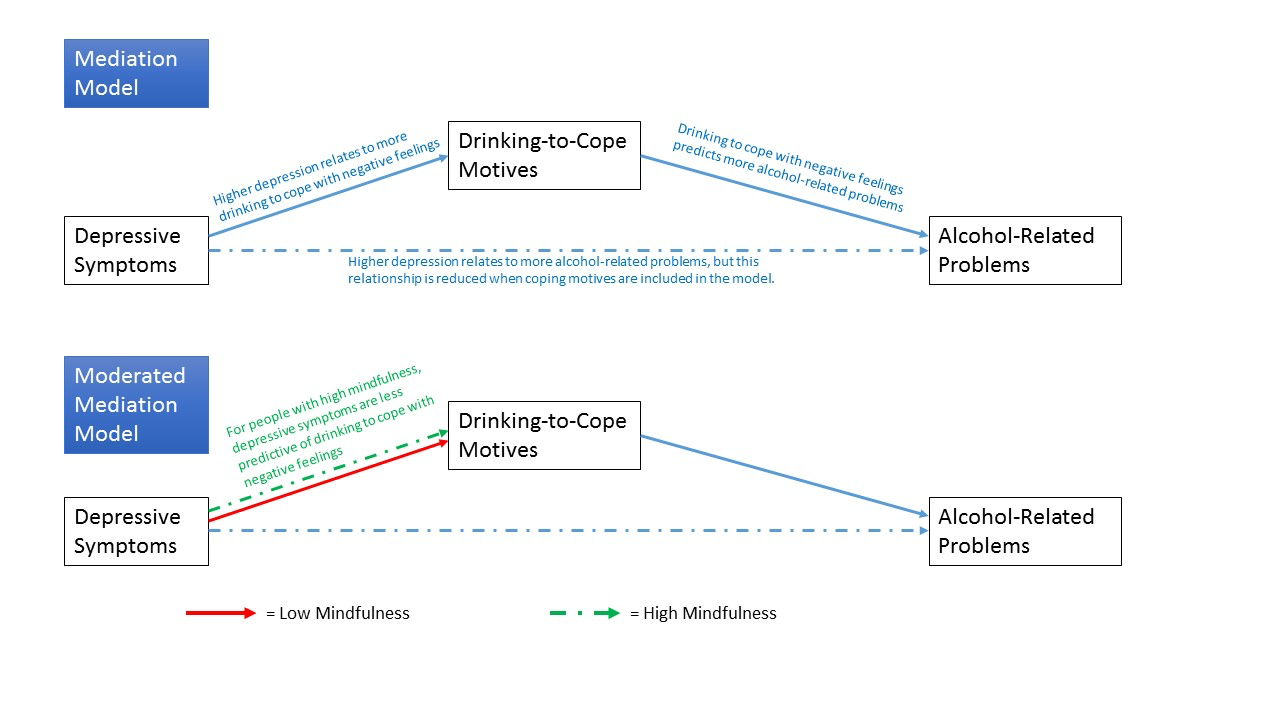

As expected, respondents with more depressive symptoms reported more alcohol-related problems, and that relationship was mediated by drinking-to-cope motives (see Figure). Respondents who were depressed were more likely to use drinking to cope with negative feelings, and drinking to cope was related to experiencing more alcohol-related problems. However, as shown in the bottom half of Figure 1, mindfulness was a moderator of this relationship. The association between depression and drinking-to-cope motives was reduced for individuals high in mindfulness.

Figure. Path diagram showing the relationships between depressive symptoms, drinking-to-cope motives, and alcohol-related problems, for those reporting low and high mindfulness. Adapted from Bravo et al. (2016). Dashed lines indicate weaker relationships than solid lines. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

If people who are naturally more mindful are able to resist drinking as a way to cope with negative emotions and choose healthier coping mechanisms, it is possible that teaching mindfulness can promote these same positive outcomes. There is a growing body of knowledge on how to teach mindfulness. As the study and understanding of mindfulness evolve, both within and outside academia, perhaps more people will become open to spending time on mindfulness training, potentially leading to a strengthening of the overall mental health of the population as a whole.

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

The sample was a volunteer sample from a single university. The results may not be generalizable to the greater college student population, or to other age groups or demographics. This study also did not study people across time, so it cannot test whether the relationships it found were causal or whether one experience (e.g., depression) came before another (e.g., alcohol-related problems).

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has information on alcohol use disorder here.

— Matthew Tom

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Michael Abbott April 5, 2017

This article refers to a long-standing recognition of a correlation between substance use and mental health. This reminds me of the long-standing efforts to assign a cause-and-effect relationship between psychoactive substance use and mental health problems. The DSM-V contains diagnoses such as substance-induced anxiety and mood disorders. While these situations do exist, It is my impression that there is a tendency to over utilize these diagnoses to imply an unsupportable cause and effect, which becomes a distraction in providing treatment. It also supports a stigma about substance use disorders. We don’t refer to mental health disorder-induced substance use disorders, even though this is by far more common that the other way around. I am just saying……