People suffering from anxiety disorders often drink to cope with that anxiety (Carrigan & Randall, 2003; Kushner, Abrams, & Borchardt, 2000). Those who have Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) might be particularly prone to this type of self-medication behavior because social situations and alcohol tend to go together. It follows that for those with SAD, drinking motives might mediate the relationship between SAD and alcohol problems. This week, the DRAM reviews a recent study that examined the specific relationship between SAD and coping motives for drinking (Windle & Windle, 2012).

Methods

- The sample consisted of a subgroup of 717 individuals from the Lives across Time (LAT) prospective study of 1205 adolescents who had available data on all variables of interest in high school and at the young adult follow-ups.

- The first four waves of data collection were conducted as in-school surveys among sophomores and juniors and separated by 6 months.

- The last two waves were conducted as in-person interviews and separated by 5-6 years, occurring when the participants were, on average, 23 and 29 years old.

- Measures

- During both adolescence and young adulthood, researchers assessed drinking motives (i.e., coping, enhancement, and social) using scales derived from Cooper et al. (1992).

- During adolescence, researchers measured depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), as well as quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption during the past 30 days.

- During young adulthood, interviews included the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler & Ustun, 2004) to measure lifetime history of depression and multiple anxiety disorders.

- Linear regression models with each of the three young adulthood drinking motives as outcomes, lifetime depression and anxiety diagnoses as predictors, and adolescent alcohol use and coping motives as control variables, assessed the relationship between SAD and drinking motives.

Results

- Thirteen percent of the participants qualified for SAD during their lifetime.

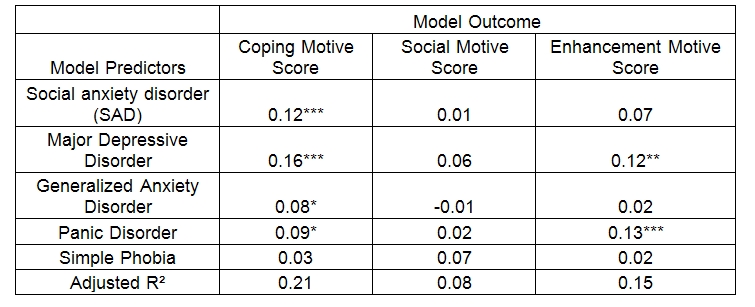

- Researchers found that SAD predicted endorsement of coping drinking motives (while controlling for prior relevant adolescent variables and other lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders), but not social or enhancement motives (see Figure).

- Major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder also predicted endorsement of coping drinking motives.

Figure. Standardized regression coefficients for lifetime disorder history predictors of drinking motives in young adulthood (adapted from Windle & Windle, 2012). ***p < 0.001; **p < .01; * p < 0.05. Note: All regression models included the following adolescent variables as control variables: adolescent coping motives, alcohol use, and depressed affect. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The sample is predominately white, suburban and middle class.

- Self-report was used as a means for data collection which may cause bias that might affect the findings.

- Regression analysis only accounted for low to moderate levels of variance in young adult drinking motives.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that SAD is associated with the endorsement of coping motives for drinking, but not social or enhancement motives. However, other anxiety and depressive disorders were also strongly associated with coping motives. These findings suggest that coping motives for drinking might result from general mental distress, rather than specific social anxiety. Either way, if coping motives for drinking are indicators of self-medication and attempts to relieve stress related to anxiety or depression, then specific alcohol problem prevention models can be developed to help alleviate unpleasant emotional and/or physiological symptoms characteristic of these disorders. Cognitive behavioral interventions that aim at replacing drinking as a coping mechanism with positive cognitions and skills would equip individuals with better tools to deal with emotions and stressors.

– Paige Shaffer

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Carrigan, M. H., & Randall, C. L. (2003). Self-medication in social phobia: a review of the alcohol literature. Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 269-284.

Cooper, M. L., Russell, M., Skinner, J. B., & Windle, M. (1992). Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment, 4 (2), 123-132.

Kessler, R. C., & Ustun, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(2), 93-121.

Kushner, M. G., Abrams, K., & Borchardt, C. (2000). The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 149-171.

Windle, M., & Windle, R. C. (2012). Testing the specificity between social anxiety disorder and drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors, 37(9), 1003-1008.