As the United States was closing an important chapter in its gambling history by completing a review of the impact of gambling on American society [1, 2], the British were gearing up for a national prevalence survey. During June of 2000, the results of the British gambling prevalence survey were released [3] . Since the British have had a longer relationship to legalized gambling than the Americans, this report is of great interest and might portend the future of gambling in the United States.

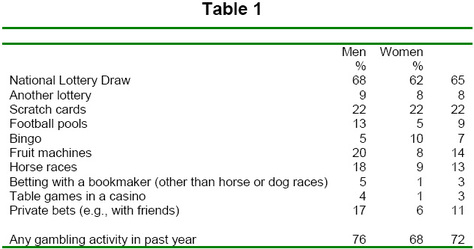

British men and women gamble regularly and participate in varied forms of gambling. Table 1 illustrates some of these gambling patterns for men (N=3745) and women (N=3955) from the general population (age 16 and older).

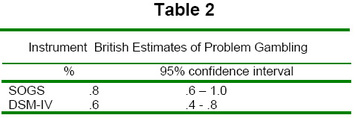

Regarding the prevalence of gambling disorders, the British study employed two different population screening measures. They used both the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) to establish identification criteria for "problem gambling." They applied a cutoff of 5 or more positive responses for the SOGS and only 3 or more positive responses on the DSM-IV criteria to establish the presence of problem gambling.

Readers should note that DSM-IV does not include problem gambling as a diagnostic category, only the most serious form of gambling disorder (i.e., pathological gambling). Also, DSM-IV requires 5 or more positive responses to satisfy the current criterion for pathological gambling. Taken together, the British have used a somewhat more liberal system for generating prevalence estimates than other studies. Table 2 summarizes the past year estimates of problem gambling yielded by these screening devices.

This study reveals that while the British are very involved in gambling, the prevalence of problem gambling is lower than among their American counterparts-even when using a more liberal model for generating these estimates. Perhaps these lower estimates reflect differences in cultural attitudes, context or experience with gambling; only time will tell. In the next WAGER, we will examine different prevalence estimates and consider the issue of validity as this relates to estimating the prevalence of gambling disorders.

References

[1] National Gambling Impact Study Commission. (1999). National Gambling Impact Study Commission Report. Washington, D.C.:

[2] National Gambling Impact Study Commission. National Research Council. (1999). Pathological gambling: a critical review. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

[3] Sproston, K., Erens, B., & Orford, J. (2000). Gambling behaviour in Britain: results from the British gambling prevalence survey. London: National Centre for Social Research.