Gaming disorder (GD) is characterized by impaired control over playing video games and a continuation or escalation of gaming despite negative consequences. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a popular approach for quickly identifying and addressing substance use disorders, and it may also be beneficial for gaming problems. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Jennifer J. Park and colleagues that examined clinician attitudes toward and approaches to screening, treatment, and referral for GD in addiction and youth service settings.

What were the research questions?

What are clinician attitudes toward screening for GD in addiction and youth service settings? Which behavioral change techniques would clinicians use to treat GD, and how confident are clinicians in using each technique?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers surveyed 88 experienced clinicians (e.g., counselors, psychologists, social workers) who provide SBIRT to adolescents or adults from 35 gambling, substance use disorder, and youth service programs across New Zealand. They reported their average monthly caseload of clients with GD and completed questionnaires that assessed their attitudes toward screening for GD and the actions they would take if GD was detected in a client. Participants also reported the types of behavioral change techniques1 they would use to treat GD and their level of confidence with each technique. The researchers calculated frequencies, averages, and percentages for the survey items.

What did they find?

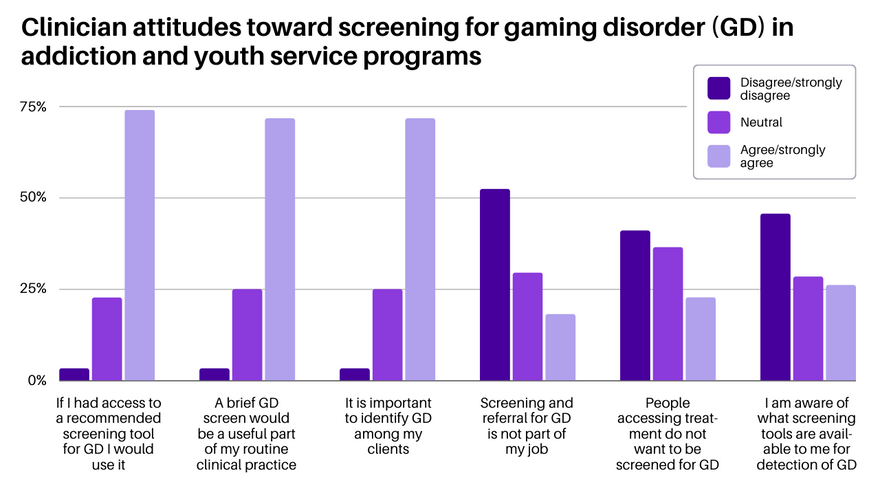

Most clinicians had at least one consultation in the past year with someone with gaming-related problems (84.1%) and reported a mean monthly caseload of 4.1 individuals experiencing gaming problems. The majority of clinicians felt somewhat comfortable or very comfortable with screening for GD. Barriers to screening included lack of clinician awareness of available screening tools and the perception that people accessing services would not want to be screened for GD (see Figure). Nearly one-fifth of participants felt that screening and referral for GD is not a part of their job.

Figure. Clinician attitudes toward screening for GD in addiction and youth service programs, with the percentage of clinicians (n = 88) who agreed/strongly agreed, felt neutral, or disagreed/strongly disagreed with each statement. Click image to enlarge.

Most clinicians agreed that if a client disclosed a gaming problem they would administer a screen, conduct further assessment, or help address immediate gaming-related harms. About one-third of clinicians indicated they often or always refer the client to another agency. Clinicians reported they generally felt confident in delivering behavioral change techniques, including motivational interviewing, relapse prevention, problem-solving, and skill-building. They felt less confident in using behavioral change techniques that require gaming-specific knowledge, such as exposure therapy, social comparison, and imaginal desensitization. Finally, 58% of clinicians had attended a general information session about GD, yet few reported receiving training on screening or treatment for GD.

Why do these findings matter?

This study found that clinicians in addiction and youth service settings were largely supportive of providing SBIRT for gaming-related problems, but that challenges and barriers exist. Challenges, including lack of awareness of appropriate screening tools and low-to-moderate confidence in applying treatment techniques that require gaming-specific knowledge, might be addressed through training. Clinicians might benefit from increased education around gaming, such as the 15-hour Foundations in Gaming Disorder course. The low referral rate to external treatment or support potentially reflects the absence of referral pathways and specialized gaming treatment options in New Zealand. This finding points to the need for a comprehensive healthcare approach to support individuals with gaming-related problems.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

The actual prevalence of gaming-related problems in addiction and youth services cannot be determined from this study because this study only included clinicians who had provided care to at least one individual with an internet-enabled addiction. Findings from this study might not be generalizable to other types of clinical settings (e.g., primary care) and geographic locations outside of New Zealand.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a problem with gaming? Visit this webpage hosted by the Evergreen Council on Problem Gambling for treatment and support services for gaming disorder and internet addiction. For additional resources related to addiction, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Kira Landauer, MPH

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Behavioral change techniques were broken up into four categories: (1) assessment and psychoeducation, (2) motivational enhancement, (3) cognitive and behavioral therapy, and (4) skill-building.