Sadly, about 1 in 20 adults worldwide are living with an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Equally discouraging is the fact that only about 1 in 6 adults receive treatment for their AUD. There are several reasons why a person may choose not to seek treatment, including shame, stigma, and misconceptions of the recovery process. Physical activity is an unassuming form of treatment that does not present some of these barriers. Previous studies have suggested that physical activity can improve a person’s mood and decrease alcohol cravings. This week, The DRAM reviews a study by Victoria Gunillasdotter and colleagues that examined how exercise and phone-based clinical treatment compare when it comes to decreasing alcohol consumption among people with AUD who haven’t sought treatment.

What was the research question?

Do yoga and/or aerobic exercise influence drinking outcomes in a comparable way to phone based clinical support delivered by an alcohol treatment specialist?

What did the researchers do?

The authors used advertisements to recruit participants living in Stockholm, Sweden who were diagnosed with an AUD and reported hazardous drinking in the past month, did not regularly engage in exercise, and were not already seeking treatment for AUD. One hundred and twenty-four participants completed the study. The researchers randomly assigned the participants to one of three treatment groups: (1) yoga or (2) aerobic exercise (each consisting of 1-hour group training sessions facilitated by qualified instructors at least three times per week), or (3) treatment as usual (TAU; in this case, up to 3, 45-minute clinical phone support sessions delivered by a specialist). The study team conducted assessments at baseline and again thirteen weeks later to measure weekly alcohol consumption and secondary outcomes. Gunillasdotter and her colleagues used intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses to analyze changes in outcomes and used analysis of covariance to compare group differences.

What did they find?

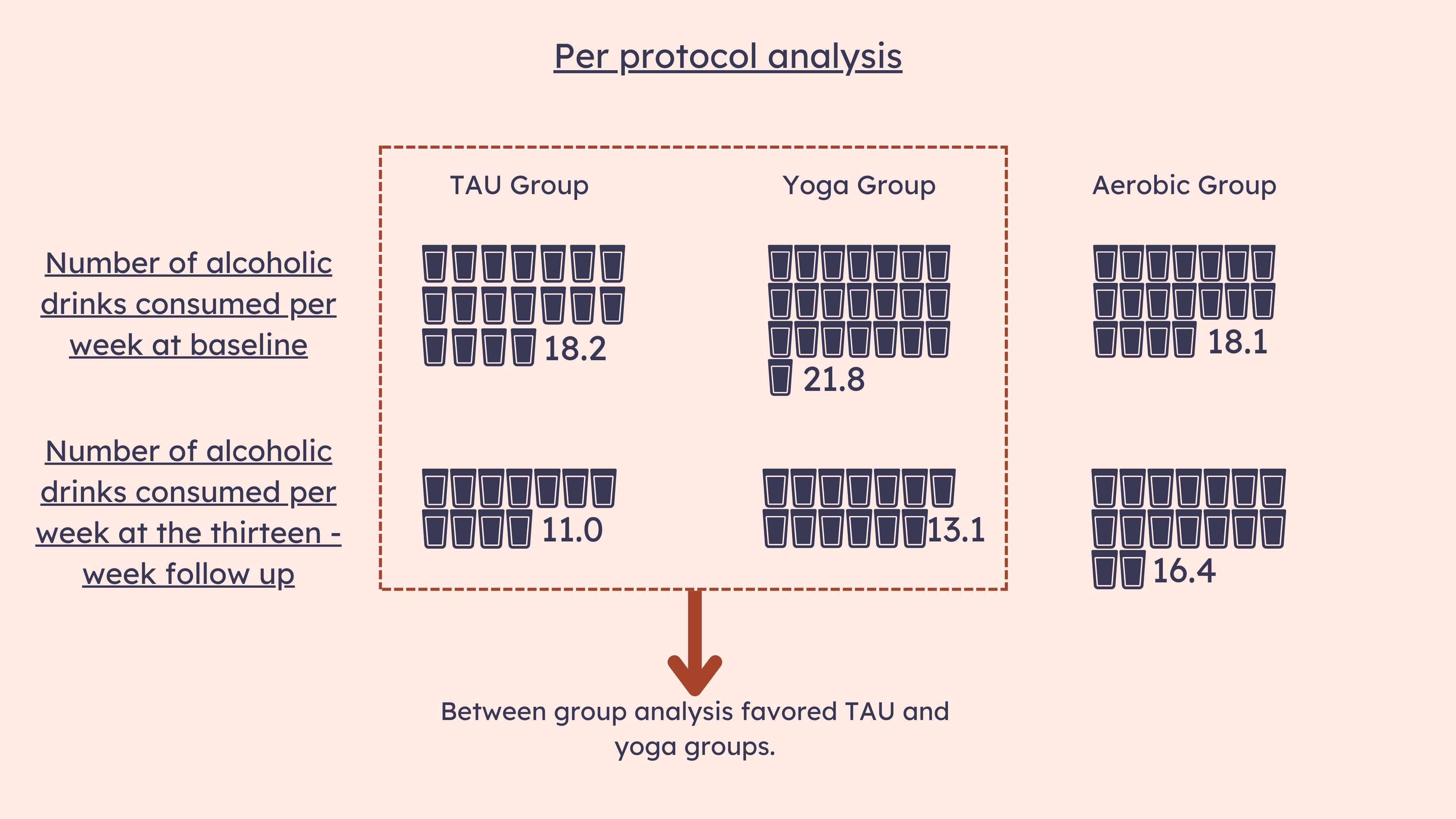

Before beginning treatment, participants drank an average of 19.7 drinks per week. The ITT analysis identified similar levels of decreases in alcohol consumption across all three groups. The PP analysis favored the TAU and yoga groups over the aerobic group, suggesting that yoga-based exercise has comparable effects to phone-based clinical treatment at reducing alcohol consumption (see Figure). It is also worth noting that at the thirteen-week follow up, yoga group participants reported the largest decrease in hazardous alcohol consumption, even when compared to TAU. They went from 21.8 drinks per week to 13.1.

Figure. Number of alcoholic drinks consumed by participants per week. This data was gathered at baseline and again at the thirteen-week follow up. The per protocol analysis favored the TAU and yoga groups compared to the aerobic group. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Exercise could be a non-stigmatizing way for individuals who have not previously sought treatment to limit their alcohol consumption. Even as a stand-alone treatment, exercise reduced weekly drinking, indicating that minimal weekly exercise is comparable to brief clinical treatment. Especially barring any other health issues, physical activity is a relatively easy intervention to implement into primary care or more specialized AUD treatment. Branding it as “lifestyle focused” treatment may also decrease associated stigma, opening the possibility of treatment to those who are more reluctant to engage in more formal practices.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

Participation in exercise was low despite offering motivational influences such as personal trainers. Because the study period was only thirteen weeks, there was no way to measure multi-year or longer-term effects. Within yoga and aerobic activities, participants had different options (e.g., ashtanga and hatha yoga, yin yoga, yin release, cycling/spinning, boxercise, dance), and it is unknown whether specific options had a greater or lesser effect on alcohol consumption. Lastly, simply being enrolled in a study and reporting one’s drinking habits could have contributed to these improvements, a phenomenon known as assessment reactivity. It’s unclear whether these effects would emerge outside a study context.

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For additional drinking self-help tools, please visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.