Some evidence suggests that heavy cannabis use can increase the likelihood of self-harm and mortality. There is also concern that cannabis use is associated with violence. Because consumption of cannabis likely increases with its ease of availability, states that have legalized the commercial sale of cannabis could experience increases in rates of self-harm and assault relative to states that do not yet have a legal marketplace for cannabis. Insofar as the legalization of recreational cannabis increases overall cannabis use more than the legalization of cannabis for medical treatment only, one would expect that states that legalized recreational cannabis would experience larger increases in self-harm and assault than states that have only legalized medical cannabis. In this edition of STASH, we review an open-access study by Ellicott Mathay and colleagues that tested these predictions by comparing state-level rates of self-harm and assault before and after cannabis legalization.

What were the research questions?

Does the legalization of marijuana correspond to an increase in self-harm or assault injuries? If so, is the effect larger for recreational marijuana than medical marijuana, and/or for some demographic groups than others?

What did the researchers do?

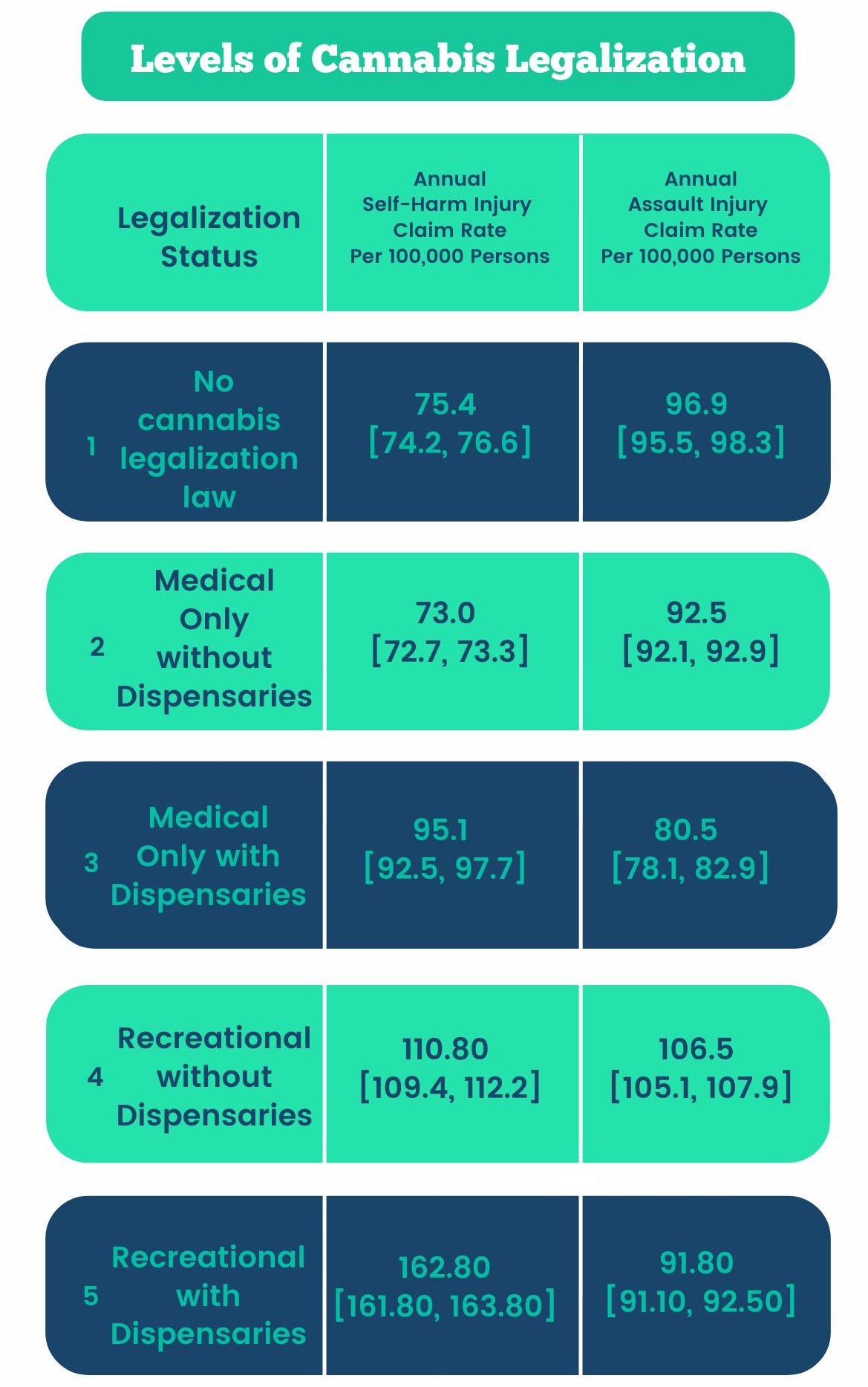

The authors retrieved medical claims, including those based on incidents involving self-harm and assault, filed from 2003 to 2017 in the United States from Clinformatics Data Mart. They then retrieved changes in recreational and medical cannabis laws from publicly available sources. They represented state-level legal changes in the data analysis using a 5-level variable for increasing degrees of cannabis legalization (see Figure).

The authors used fixed-effect models to examine changes in monthly, state-level rates of injury claims caused by self-harm and assault as a function of degree of cannabis legalization. The main benefit of the fixed-effect approach is that it enabled the authors to statistically control for several factors even though they were not actually measured, including: (1) stable differences between states that could explain why some states consistently have higher rates of self-harm and assault than others (e.g., Montana consistently has higher rates of suicide than Massachusetts; the reasons for this are probably numerous), (2) yearly changes that affect all states similarly (e.g., more potent cannabis products), and (3) seasonality in rates of self-harm and assault (e.g., hot temperature is associated with more self-harm and assault). The authors also included controls for several other state-level variables that change over time, such as median income.

Figure. Categories of cannabis legalization and pooled rates of self-harm and assault injuries in states with a given cannabis legalization category. All states with legal recreational cannabis also had legal medical cannabis. The same states contribute to different annual rates over time, depending on how their cannabis legalization status changes. The numbers in brackets are 95% confidence intervals. Click image to enlarge.

What did they find?

In general, neither medical nor recreational cannabis laws had significant associations with assault. However, compared to states with no laws legalizing medical or recreational cannabis, states permitting recreational dispensaries without dose-related restrictions had statistically significant increases in assault among individuals younger than 21 years old. Specifically, the rate ratio for females was 2.14 and for males was 2.29.

Cannabis legalization were also generally not associated with rates of self-harm, except that recreational cannabis legalization without dispensaries was associated with increased self-harm for males younger than 21 (rate ratio = 1.70), and recreational cannabis legalization without dispensaries increased self-harm for males aged 21-39 years (rate ratio = 1.46).

Overall, current evidence points to specific demographic groups that are at higher risk of experiencing self-harm or an assault injury as a result of recreational cannabis legalizing cannabis, but does not demonstrate an increased risk that generalizes across demographic groups.

Why do these findings matter?

The effect of recreational cannabis, but not medical cannabis, on self-harm suggests that the profit incentives inherent to commercialized industries could increase cannabis use (e.g., via increased advertising, more potent strains, etc.) in ways that make self-harm or assault injuries more common. The specificity of the results to younger males suggests a need for interventions that appeal to this subpopulation specifically. For instance, a recent randomized trial incorporated a smartphone app into an intervention for young adults who wanted to reduce their cannabis use. Participants reported that the app was helpful in reducing their cannabis use.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

Incidents of assault and self-harm involving individuals without private insurance are missing from the dataset, as well as incidents that did not result in a medical claim. Also, while fixed-effect models are highly useful, their validity depends on assumptions that are difficult to verify.

For more information:

If you are worried that you or someone you know is experiencing addiction, the SAMHSA National Helpline is a free treatment and information service available 24/7. For more details about addiction, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— William McAuliffe, Ph.D.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.