The “opioid epidemic” is a problem that many urban communities of color have been experiencing since as early as the 1940s. However, instances of opioid overdoses have increased exponentially since then, with 72,000 overdose deaths in 2017 alone, many of which are thought to have been induced by fentanyl-contaminated heroin. Recent narratives of the epidemic often come in white-washed forms, depicting rural or suburban, White Americans as the predominant victims. For example, the sequence of use that is typical among rural/suburban White Americans — starting with prescription opioids and moving on to heroin when legal access is cut off — often fails to capture the reality of opioid use and dependence in urban communities of color. Blythe Rhodes and colleagues worked to fill in that gap of knowledge through a qualitative study that interviewed urban individuals of color on their experiences with fentanyl-contaminated heroin. We review their study in this week’s STASH.

What was the research question?

How is the current, fentanyl-fueled opioid epidemic impacting urban, minority users?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 25 participants on-site from a syringe access program in North Carolina, and by referral from syringe exchange staff or other participants. All participants were 18 or older and recent injection users — 19 were Black, 5 were multiracial, 1 was White, and 3 identified as Hispanic. The researchers conducted interviews with each participant privately at a community center or over the phone. Participants were asked about their pathways to injection drug use, experience with overdose, use of harm reduction services, experiences with fentanyl, contact with law enforcement and previous incarceration, and HIV risk and prevention strategies.

The researchers used an inductive approach for analysis.

What did they find?

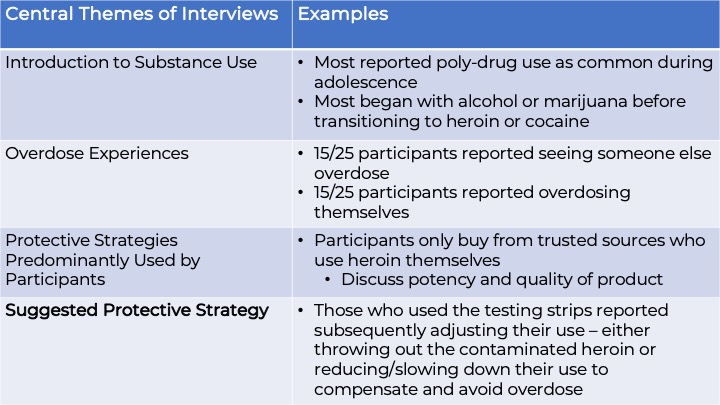

Of the 25 participants, only three reported that their illicit drug use began with legally prescribed opioids. Most reported that their use of cocaine and heroin began with alcohol or marijuana. Many reported that illicit poly-drug use was normalized within their adolescent social networks.

Fifteen of the 25 participants had witnessed someone else overdose, with some having seen multiple overdoses. Likewise, fifteen of the 25 reported experiencing non-fatal overdoses themselves in the past two years. Eight of them believed that their overdose could have been attributed to fentanyl-contaminated heroin. Most participants reported recognizing fentanyl in their products through the “feel” or type of high they experience. They reported that when fentanyl is present, they experience the shakes, sweats, brownouts or memory loss, difficulty breathing, feeling light-headed and vomiting. Some participants said that when they detected fentanyl, they threw out the remaining heroin or used less that day at a slower pace. Only four participants reported using fentanyl testing strips given to them by harm reduction agencies. The most commonly reported method for detecting fentanyl was visual inspection of the color, with varying results.

Most of the exposure to fentanyl was without the knowledge of the participants and usually occurred when they were unable to buy from sellers they knew and trusted. No participant reported actively seeking out fentanyl and many reported no longer buying from sellers with known mixes of fentanyl. Many participants preferred to buy from trusted sellers who were also known users, as this gave them more security in the quality of the heroin they purchased.

Figure. Central Themes from Interviewing Urban Individuals of Color on Their Experiences with Heroin. (Rhodes et al. 2019) Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Most users in this study sought to avoid products laced with fentanyl and have adopted safety strategies to try to avoid the negative consequences (e.g., adjusting their intake once they know their product is laced). Educating users about fentanyl testing strips could encourage more of them to use the testing strips as a more effective harm reduction strategy, rather than relying on their high as an indicator.

We need to shift focus away from the demonizing of drug users in urban communities of color that leads to over-policing. Over-policing is harmful to communities of color in countless ways. For instance, arresting heroin dealers might negatively impact the community by forcing users to turn to outside, untrusted sources that more often than not lead to fentanyl contamination. Instead of denouncing drug users and sellers of color, we should focus on increasing harm-reduction strategies like safe injection facilities and the distribution of fentanyl testing strips, which can change the behavior of users and might lead to a decrease in overdoses.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The study is limited by its small sample size which restricts the ability to generalize to a wider population. Additionally, individuals who regularly frequent harm-reduction agencies may differ from the larger injecting population and may not be representative of others’ experiences with fentanyl and overdose.

For more information:

Are you worried that you or someone you know has an addiction? The SAMHSA National Helpline is a free treatment and information service available 24/7. For more details about addiction, visit our Addiction Resources page.

Health professionals and addiction specialists have been increasingly focused on mental health as it pertains to COVID-19. They have assembled substance use resources specific to COVID-19-related concerns, as well as resources on substance use in general, which can be found on the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites.

— Karen Amichia

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.