Today's review is part of our month-long Special Series on Race and Addiction. During this Special Series, The BASIS addresses addiction-related discrimination, social determinants of health, health equity, and race.

We are in the midst of widespread social movement in support of racial equality and anti-racism. This includes developing a better understanding of how experiences with racism can contribute to health disparities. While research shows that African Americans drink less yet suffer from higher rates of alcohol-related problems than other racial groups, little is known about the impact of racism on drinking or the potential protective effects of racial socialization (i.e., learning to feel pride in one’s racial/ethnic group, learning how to cope with racial bias, and becoming prepared for bias). In this week’s DRAM, part of our Special Series on Race and Addiction, we review a study by Jinni Su and colleagues that examined how experiences of overt racism and more subtle racism (i.e., microaggressions) were associated with drinking and drinking problems among African American young adults.

What was the research question?

What is the role of racism in the development of alcohol problems among African American young adults?

What did the researchers do?

Respondents—383 African American students at a large public university—reported1 how often they experienced overt racism and microaggressions, experiences with racial socialization by parents and friends, and both frequency of alcohol use and negative consequences related to drinking. Next, the authors used hierarchical linear regression models with control variables including gender and parental education to determine: (1) whether there is a positive relationship between experiences of racism, drinking frequency and alcohol-related problems, and (2) whether racial socialization can protect against the adverse effects of racism on alcohol use behaviors.

What did they find?

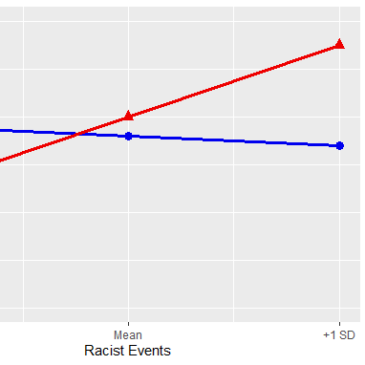

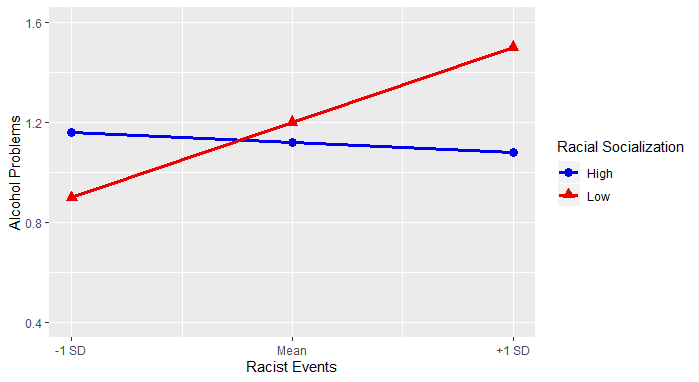

Experiencing microaggressions was positively associated with drinking more and having more severe alcohol problems, whereas experiencing overt racism only predicted more severe alcohol problems. Racial socialization in the form of instilling pride in one’s racial/ethnic group by friends reduced the effects of experiencing overt racism on the two outcomes (see figure for racist events and alcohol problems model). Racial socialization by parents did not influence the relationship between either racism indicator and the drinking measures.

Figure. Figure shows relationship between experiencing overtly racist events and alcohol problems when racial socialization is high (blue line with circles) versus low (red line with triangles). SD = Standard deviation. “High” refers to being one SD above the mean for racial socialization and “Low” refers to being one SD below the mean for racial socialization. In particular, the dimension of racial socialization portrayed here is instilling pride about one’s racial or ethnic group. The relative flatness of the blue line shows how racial socialization buffers the effects of racist events on alcohol problems. Click figure to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The results are important for developing greater scientific and public awareness about the pervasive public health consequences of racism. Importantly, this study showed that racism is associated with alcohol-related problems among African Americans, regardless of the type of racism (i.e., microaggressions and overtly racist events). The harm from individual, systemic and institutional racism is far-reaching, and an anti-racism education curriculum—along with positive racial socialization by peers—might help reduce racism and related adverse outcomes. Moreover, this study highlights the need for substance use intervention programs that are culturally relevant for each racial and ethnic group, instead of relying on a one-size-fits-all approach. Recent research has revealed that drink refusal and social pressure skills training have different impacts for African American and white participants, emphasizing the importance of targeted, culturally relevant programs for addiction treatment.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The respondents in the sample were primarily female (i.e., 81%) and were all African American, so the results might not generalize across genders or to other racial and ethnic groups. Recall bias might have also affected respondents’ reports of racism and drinking behaviors due to difficulties in remembering past events.

For more information:

The National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

In response to recent events, mental health professionals and others have been increasingly focused on mental health as it pertains to racism. Many of these discussions, as well as resources on health equity in general, can be found on the American Public Health Association and American Medical Association websites.

— Eric R. Louderback, Ph.D.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Overt racism was measured by asking respondents about the frequency with which they had experienced 17 racist events, such as “How many times in the past year have you been treated unfairly by teachers and professors because you are Black?”. Racial microaggressions included 45 items, measured by questions such as: “Someone assumed that I would have a lower education because of my race” and “Someone avoided walking near me on the street because of my race”. Racial socialization included 10-items for the parental domain, with questions tapping the feeling pride in one’s racial/ethnic group dimension (e.g., “Growing up, how often did your parents talk to you about important people or events in your group’s history?”), preparation for bias dimension (Growing up, how often did your parents tell you that you must be better to get the same rewards with others because of your race?) and promotion of mistrust dimension (Growing up, how often did your parents do or say things to encourage you to keep distance from people of other races?). These same 10 items were adapted to measure racial socialization for the friends’ domain, with versions that referred to friends instead (e.g., “Growing up, how often did your friends talk to you about important people or events in your group’s history?”).