Today’s review is part of our month-long Special Series on Race and Addiction. During this Special Series, The BASIS addresses addiction-related discrimination, social determinants of health, health equity, and race.

In the last two decades almost 450,000 people have died from opioid overdoses in the United States. The death and relapse rate is even higher among people who have been incarcerated, who, due to racist policing and policies, are disproportionately people of color. Opioid agonist drugs, which are effective for managing the craving and withdrawal associated with long-term opioid dependence, are routinely withheld from people involved in the criminal justice system. Extended-release naltrexone, a sustained-release monthly injectable opioid antagonist, is an option that is less likely to be withheld because it has no known abuse potential. This week, as part of our Special Series on Race and Addiction, STASH reviews a study by Joshua D. Lee and colleagues that examined the effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone in preventing opioid relapse in criminal justice-involved people.

What was the research question?

Is extended-release naltrexone effective in preventing opioid relapse among community-dwelling people with prior involvement in the U.S. criminal justice system, compared to usual treatment?

What did the researchers do?

Inclusion criteria for volunteer participants was being an adult living in the community with criminal justice involvement,1 current or lifetime opioid dependence, a stated goal of opiate-free treatment instead of opiate-agonist maintenance therapy and current opioid-free status (confirmed by urine test). 77% percent of the participants were Black or Hispanic. The treatment group was assigned to a 24 week extended-release naltrexone regiment (injection once a month) and the control group received the usual treatment (brief counseling and referrals for community treatment programs). The amount of time to an opioid-relapse event was the primary outcome. This was obtained by self-report or by testing of urine samples obtained every 2 weeks during the 24 week period. Post-treatment follow-up took place at week 27, 52, and 78.

What did they find?

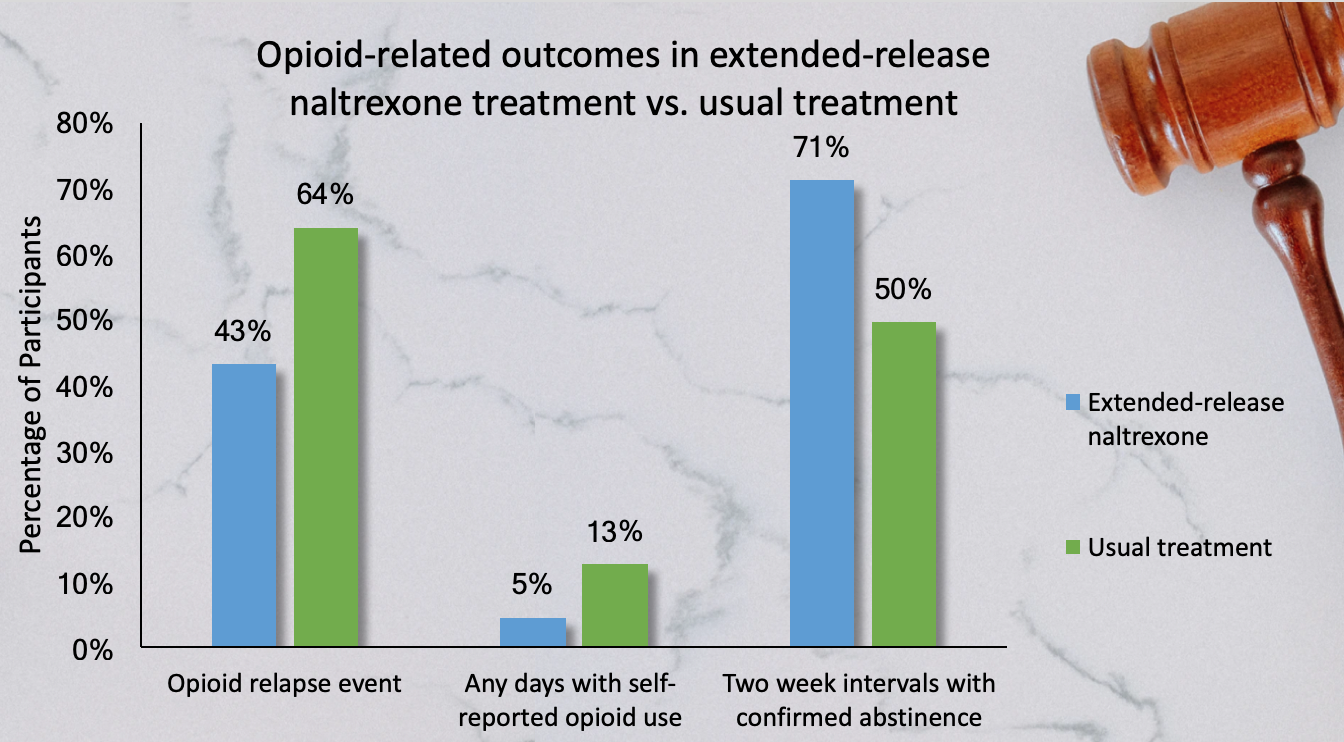

Time to relapse in the extended-release naltrexone group was 10.5 weeks compared to the treatment-as-usual group, which averaged 5 weeks until relapse. Additionally, the extended-release naltrexone group had a lower percentage of participants with an opioid relapse event, lower percentage of of any days with self-reported opioid use and a high percentage of two week intervals experience an opioid relapse event during treatment at all higher percentage of two week intervals with confirmed abstinence (see figure). Interestingly, a year after treatment there was no significant difference in percentage of participants who remained abstinent between groups.

Figure. Opioid-related treatment outcomes in extended-release naltrexone treatment vs. usual treatment in criminal justice offenders. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The results demonstrate an effective way to prevent patients from relapsing or at least prolong relapse. Extended-release naltrexone is both effective and has no abuse potential. This will likely be more readily accepted by treatment facilities who fear incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people will abuse opioid agonist treatments. As such people are disproportionately people of color (this sample was 77% Black or Hispanic) this may offer one potential method to begin to undo the inequity within our healthcare and criminal justice system. Serious subsequent steps will be needed as well.

Unfortunately, there was no difference between groups one year after the treatment. Further research should examine if naltrexone treatments lasting longer than 24 weeks will sustain the positive impact that the drug provided.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The methodology of this study fails to address two key psychological phenomena that can have been shown to influence or obstruct experiments. First, the study is not double blind. This means researchers could unknowingly influence the outcome by treating the groups differently. Additionally, there is no placebo group. This shortcoming fails to eliminate the possibility that the effects of the extended-release naltrexone are due solely to the patient’s belief in the drug.

For more information:

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institute on Drug Abuse list treatment options for opioid use disorder. Our Addiction Resources page has free, anonymous resources for people concerned about substance use or other expressions of addiction.

— Alex LaRaja

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Defined as receipt of an adjudicated sentence that included supervision (e.g., parole, probation, outpatient drug-court programs, or other court-mandated treatment) or, in the previous 12 months, release from jail or prison, a plea-bargain arrangement, or any community supervision.

David Wilson June 9, 2020

1. How can the use of a naltrexone placebo ever be justified with human subjects who are known to use opiates?

2. 24 weeks is a tragically short treatment period. The high drop out rate from opiate use treatment provides little justification for this. My experience has been that many will continue to utilize this as a treatment adjunct for as long as it is available. Methadone programs contemplate lifelong maintenance. Increasingly this is the case with suboxone, as well. Extended release naltrexone should be similarly available. More effort needs to be expended on training counselors to learn how to work with patients for extended time periods. The results of this study demonstrate that longer treatment periods are needed if we are to see lasting results.

Alexander LaRaja June 10, 2020

Thanks for your comment David. You’re right, using placebos in human trials is not always ethical. Here I brought it up as an additional possible study arm because participants in the usual treatment condition were already not receiving any medication for opioid dependence. Also yes, long term continuation of care is certainly a weakness of many addiction treatment options. The success during treatment paired with the lack of difference between groups just a year later sheds light on why future investigation of continuation of care is critically important.