Today’s review is part of our month-long Special Series on Race and Addiction. During this Special Series, The BASIS addresses addiction-related discrimination, social determinants of health, health equity, and race.

Clinical practice guidelines require doctors to screen patients for tobacco use during each visit and to provide patients with evidence-based treatments for their tobacco use if needed. This is especially crucial for Black patients, who are disproportionately likely to develop lung cancer or die from smoking, compared to White patients, as well as people with mental health disorders, who are at greater risk for developing tobacco addiction and may turn to tobacco as a coping mechanism. This week, ASHES reviews a study by Erin Rogers and Christina Wysota that documented racial disparities in physician screening for tobacco use.

What was the research question?

How often are outpatients with a psychiatric disorder screened and treated for tobacco use, and do these rates differ based on the patient’s race or ethnicity, primary reason for treatment, and other characteristics?

What did the researchers do?

The current study’s sample came from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, a nationally representative sample of outpatient physician visits. The authors limited their sample to cases that involved a psychiatric diagnosis. The survey asked doctors to report if their patients used tobacco. The answer “unknown” to this question was coded as the doctor not having screened the patient for tobacco use. If the doctors reported “yes,” the survey also asked what treatments patients were undergoing and whether the doctors prescribed any medications. Additionally, the survey included questions relating the patient’s primary reason for treatment (psychiatric or non-psychiatric),1 expected source of payment (e.g., private insurance, Medicaid, self-pay), and their race and ethnicity. The researchers used a weighted logistic regression model in order to determine the associations between patient characteristics, visit characteristics, and tobacco screening/treatment.

What did they find?

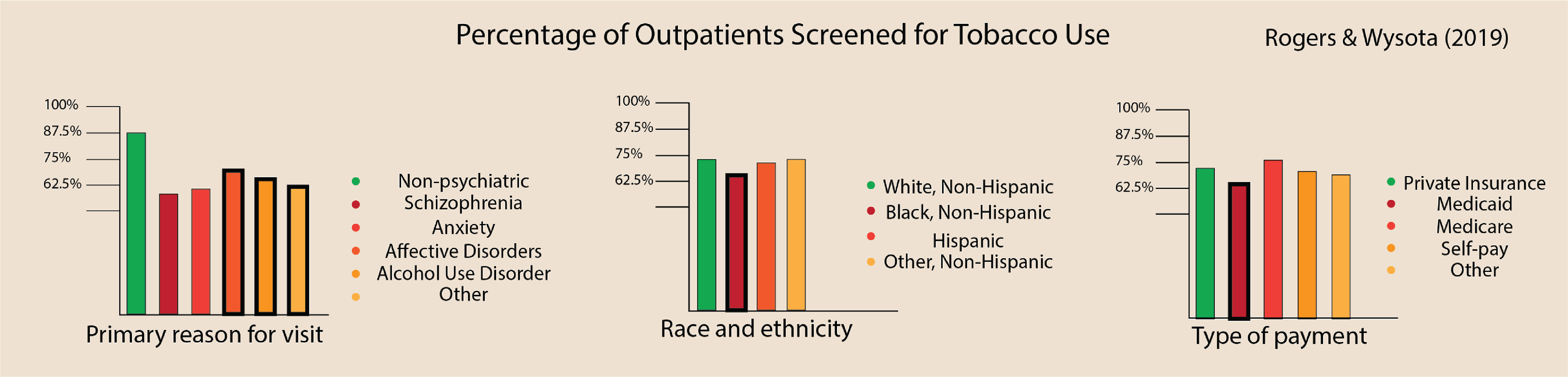

Nearly three quarters (72.4%) of patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were screened for tobacco use. Black, non-Hispanic patients had significantly lower odds of being screened compared to White, non-Hispanic patients. Patients paying with Medicaid had significantly lower odds of being screened than patients paying with private insurance. Finally, compared to visits that were primarily for nonpsychiatric reasons, visits where the primary reason was for an affective disorder, alcohol use disorder, or other psychiatric diagnosis had significantly lower odds of including tobacco screenings (see figure). Overall, 22.9% of patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were referred to some sort of treatment program or prescribed medication for their tobacco use. These factors were all independently associated with lower odds of being referred.

Figure. Percentages of outpatients screened for tobacco use by primary reason for visit, race and ethnicity, and type of payment. Bars with a bold black outline represent categories that are at significantly decreased odds of being screened for tobacco use compared to the reference category (i.e., the green bar). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

It is essential for providers to screen patients for tobacco use, as early detection and prevention can increase treatment success and reduce the rates of this preventable cause of death. This is particularly important for Black people, who are at increased risk for getting sick and dying from smoking. Unfortunately, this study’s finding is not an isolated outcome as many studies provide evidence of implicit bias against Black and dark-skinned people across the United States in the healthcare system. The results of this study also illustrate poorer care of patients who are economically deprived and are presenting for psychiatric care. It’s important that regardless of who these patients are, why they come in, and their form of payments, they are still treated holistically and with the same thoroughness as their peers. Simply acknowledging these disparities is no longer enough, we must seek active change through strategies including encouraging providers to recognize their bias, implicit bias training, and recruiting and retaining people of color in the healthcare workforce.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The survey relied on self-reported information from physicians. As such, the findings depend on the accuracy with which the physicians reported patient visits.

For more information:

SmokeFree offers tools and tips for quitting and maintaining abstinence from smoking tobacco. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information, tips, and tools about e-cigarettes and how to quit. For self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Karen Amichia

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Even though all cases that were analyzed involved a psychiatric diagnosis, the psychiatric diagnosis was not always the primary reason for treatment.