No two smokers have precisely the same history with cigarettes. People start smoking at different times in their lives, and some escalate to consistent smoking faster than others. Studying these patterns of use over time—or trajectories—helps us identify times to intervene. In this week’s ASHES, we review a multi-decade longitudinal study by Jonathan Macy and colleagues that followed both smokers and smokeless tobacco users and tracked their trajectories.

What is the research question?

What are the most common trajectories for smoking behavior and smokeless tobacco use?

What did the researchers do?

Macy and his colleagues drew from the Indiana University Smoking Survey. Over five assessments spanning 24 years[1] beginning during adolescence, participants reported their views on the links between tobacco use, cancer, and heart disease[2] and any smoking and/or smokeless tobacco use. The researchers looked at the 2,230 men who participated from start to finish and reported using cigarettes or smokeless tobacco at least once.[3] They used group-based trajectory analyses to identify trajectory groups.[4] They then looked for any associations between trajectory groups and adolescent beliefs about tobacco use.

What did they find?

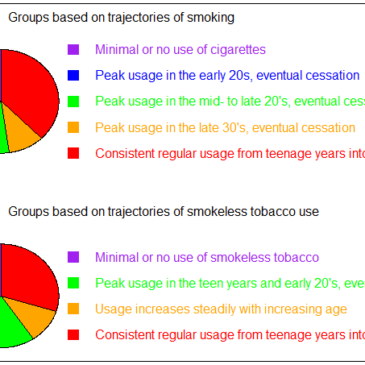

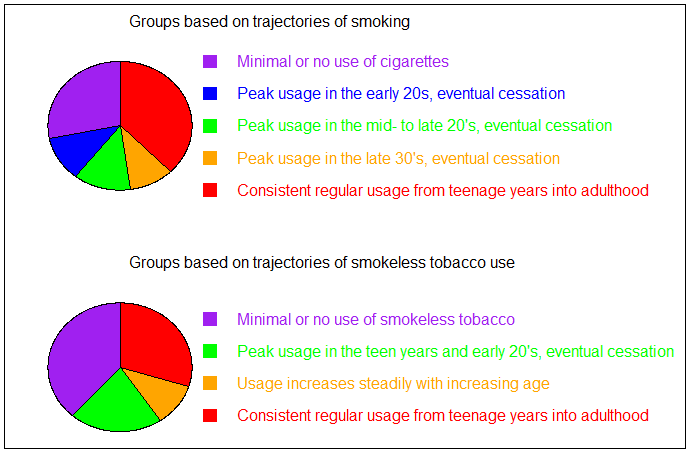

The researchers found five cigarette smoking trajectories: little to no use, peak usage in the early 20’s, peak usage in the mid- and late 20’s, peak usage in the late 30’s, and lifelong consistent use. They found four smokeless tobacco trajectories: little to no use, peak use in the teen years and early 20’s, slowly increasing use with age, and lifelong consistent use (see Figure). Adolescents who believed that cigarettes and smokeless tobacco caused lung cancer, mouth cancer, or heart disease were less likely to use these products consistently.

Figure. Pie charts displaying the relative size of each trajectory group for smoking and smokeless tobacco use. Adapted from Macy et al. (2016). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Many of today’s PSAs about smoking target teens and young adults. One series, for example, focuses on how being hooked on smoking interferes with normal schedules and daily life. Another focuses on smoking’s effect on outward appearance. However, this study linked tobacco use trajectories to beliefs about longer-term health consequences. It might be effective to air a PSA focused on long-term consequences, but targeted to younger viewers.

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

The sample was predominantly white and non-Hispanic men from the Midwestern United States. The results might not be generalizable to women or to tobacco users elsewhere around the world. The follow-up surveys were five years apart, so they were not frequent enough to show any short-term fluctuations or changes in behavior. Since the study began almost 30 years ago, typical patterns of use may have shifted since then.

For more information:

The National Cancer Institute has a website called Smokefree Teen. It provides support for teens looking to quit smoking. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also has a Guide for Quitting Smoking. On a less academic note, numerous professional athletes have spoken out about smokeless tobacco use. One example is this personal account by Curt Schilling. For additional tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Matthew Tom

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Participants reported on any tobacco use first in an initial 1987 survey, and then later in four follow-up surveys in 1993, 1999, 2005, and 2011.

[2] More specifically, participants reported whether they believed that smoking would lead to lung cancer and heart disease, and that smokeless tobacco use would lead to mouth cancer and heart disease.

[3] They only looked at males because smokeless tobacco rates were very low among females.

[4] In this case, groups of participants with similar patterns of smoking or smokeless tobacco use.