Most adults who smoke started smoking as teenagers (SAMHSA, 2006). As a result, it is important to try to reduce rates of teen smoking. For many teenagers, the decision to begin smoking stems, in part, from a desire to express a particular social identity. That is, if they identify strongly with a peer group that smokes, they might be more likely to smoke. This week’s ASHES reviews an experiment (Moran & Sussman, 2014) designed to explore whether this trend can be reversed for positive use: if adolescents view an anti-smoking ad that is linked to their own peer group, will they be more likely to reject smoking?

Methods

- The researchers recruited 534 adolescents (age 12-15) from a standing Internet panel for this study. The standing panel (N = 70,000) is similar to the United States in terms of race, ethnicity, income, and education level). The experiment took place online, in several stages.

- First, participants indicated how strongly they identified with each of 11 peer groups.

- For example, the peer group “Academics” was described as “Wears ‘regular,’ ‘normal’ clothing. Spends time studying/doing homework or other school-related clubs and activities.”[1]

- Participants were then randomly assigned to view either an anti-smoking ad targeting the group with which they most strongly identified, or an ad targeting another group.

- The ads were based on a truth® campaign print ad that showed strong research support (e.g., Cowell, Farrelly, Chou, & Vallone, 2009).

- Each ad showed two individuals (one male, one female) who represented a peer group in their clothing and objects (e.g., a guitar, skateboard, notebook).

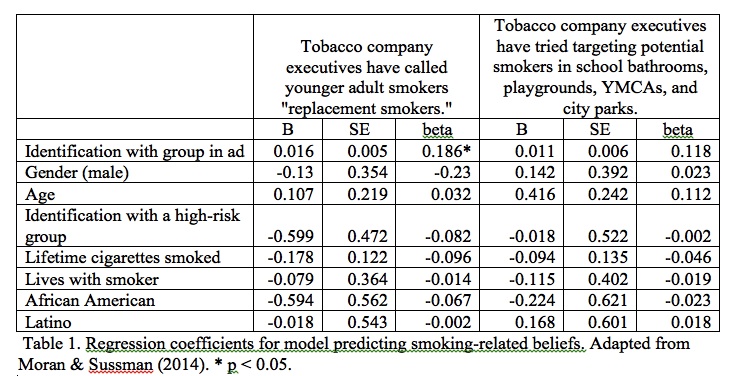

- Each ad included two anti-smoking beliefs (“Tobacco company executives have called younger adult smokers ‘replacement smokers’” and “Tobacco company executives have tried targeting potential smokers in school bathrooms, playgrounds, YMCAs and city parks.”)

- One week later, 251 of the original 534 participants reported how strongly they endorsed the two anti-smoking beliefs.

- The researchers conducted multiple regression analyses to explore the relationship between how strongly participants identified with the selected peer group and the strength of anti-smoking beliefs, controlling for demographic characteristics and other factors, including whether participants identified with a group classified as high-risk in previous research.[2]

Results

- As Table 1 shows, identification with the peer group targeted by the ad was positively associated with strength of the belief, “Tobacco company executives have called younger adult smokers ‘replacement smokers.’”

- The researchers observed the same pattern for the belief, “Tobacco company executives have tried targeting potential smokers in school bathrooms, playgrounds, YMCAs and city parks.” However, the results did not reach statistical significance.

Figure. Regression coefficients for model predicting smoking-related beliefs. Adapted from Moran & Sussman (2014). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- This study was an important first step because it examined negative beliefs about tobacco companies and their strategies. However, it remains to be seen whether these effects translate into decreases in acceptability of smoking or actual smoking behavior. Previous work suggests that expressed attitudes are only modestly related to actual behavior.

- The researchers do not indicate whether the observed effects were particularly strong for any specific peer groups. This would be an interesting question, but might require a larger sample size.

- The researchers do not provide detail regarding the recruitment of the standing Internet panel, particularly in terms of how many adolescents initially invited to join the standing panel actually joined. Low response rates could limit the representativeness of the panel.

Conclusion

Previously secret tobacco industry documents reveal that, in the past, tobacco companies studied teens’ and young adults “attitudes, social groups, values, aspirations, role models, and activities” and used their findings to develop targeted marketing strategies, in the hopes of encouraging teens to smoke and become life-long smokers (Ling & Glantz, 2002, p. 908). The current study suggests the same kind of focus on social identity might be used for positive purposes. Specifically, these results suggest that it might be possible to promote anti-smoking beliefs and behavior, along with other healthy behavior, by linking messages to adolescents’ social identities. This might be an effective strategy in the future development of health communication messages.

— Heather Gray

References

Cowell, A .J., Farrelly, M. C., Chou, R., & Vallone, D. M. (2009). Assessing the impact of the national “truth” antismoking campaign on beliefs, attitudes, and intent to smoke by race/ethnicity. Ethnicity and Health, 14, 75–91.

Ling, P. M., & Glantz, S. A. (2002). Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 908–916.

Moran, M. B. & Sussman, S. (2014). Translating the link between social identity and health

behavior into effective health communication strategies: An experimental application using antismoking advertisements. Health Communication, 29:10, 1057-1066, DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2013.832830.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2006). National Survey on Drug Use & Health. Retrieved from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh.htm.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] The peer groups used in this study initially emerged from separate survey of adolescents conducted during 2010. In that survey, participants listed up to 15 peer groups at their school and described the style, hobbies, and values of each listed peer group. Researchers classified adolescents’ responses into 11 unique peer groups.

[2] The groups considered high risk were deviant, hip-hop, rockers and emo/goth.