Next month, voters in Florida will decide whether to make that state the 24th in the nation to legalize marijuana for medical use. The heated debate in Florida – which pits some medical and law enforcement associations in opposition to the initiative against supporters who argue that it will offer patients compassion and relief—is reverberating around the nation. Today, the BASIS focuses attention on this debate by offering two opposing, but informed, viewpoints. First, we present the views of Lester Grinspoon, MD, Associate Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Grinspoon is a well-known proponent of the legalization of medical marijuana. Next, we present the view of Kevin Sabet, PhD, Director of the Drug Policy Institute at the University of Florida and an Assistant Professor in the College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry. Dr. Sabet co-founded a non-profit organization that is often critical of the medical marijuana legalization movement.

We hope these viewpoints will add to readers’ understanding of the complexity of this issue. We encourage you to add your voice to the debate using the Comment link below.

Cannabinopathic Medicine

by Lester Grinspoon, M.D.

In 1966, through my anti-Vietnam War activities, I met the man who was to become my closest friend, and through him other people who smoked the dangerous drug, marijuana. Up until then, I had never seen a joint or met anyone who had ever used one. My experience with these new friends, some of whom used it daily, led me to question my firmly held belief that marijuana was quite harmful and for that reason, in 1967, I began my studies of the scientific, medical and other literature with the goal of providing a reasonably objective summary of the data which underlay its prohibition. Much to my surprise, I found no credible medical or scientific basis for the justification of the prohibition which at that time was responsible for about 300,000 arrests annually. The assertion that it is a very toxic drug was based on old and new myths. In fact, one of the many exceptional features of this drug is its remarkably limited toxicity. Compared to aspirin, which people are free to purchase and use without the advice or prescription of a physician, cannabis is much safer: there are well over 1000 deaths annually from aspirin in the United States alone, whereas there has never been a death anywhere from marijuana. In fact, by the time cannabis regains its rightful place in the pharmacopeia around the world, it will be seen as one of the safest drugs in those compendiums. Moreover, it will eventually be hailed as a "wonder drug" just as penicillin was in the 1940s. Penicillin achieved this reputation because (1) it was remarkably non-toxic, (2) it was, once it was produced on an economy of scale, quite inexpensive, and (3) it was effective in the treatment of a variety of infectious diseases. Similarly, cannabis (1) is exceptionally safe, and (2) once freed of the prohibition tariff, will be significantly less expensive than the conventional pharmaceuticals it replaces while (3) its already impressive medical versatility continues to expand.

Given these characteristics, it should come as no surprise that its use as a medicine, legally or illegally, with or without a recommendation from a physician, is now growing exponentially around the world. Marijuana is here to stay; there can no longer be any doubt that it is not just another transient drug fad. Like alcohol, it has become a part of Western culture, a culture which is now trying to find appropriate social, legal and medical accommodations. In the United States, 20 states and the District of Columbia have established legislation which makes it possible for patients suffering from a variety of disorders to use the drug legally with a recommendation from a physician. Unfortunately, because each state arrogates to itself the right to define which symptoms and syndromes may be lawfully treated with cannabis, many patients with legitimate claims to the therapeutic usefulness of this plant must continue to use it illegally and therefore endure the extra layer of anxiety imposed by its illegality. California and Colorado are the two states in which the largest number of patients for whom it would be medically useful have the freedom to access it legally. New Jersey is the most restrictive, and I would guess that only a small fraction of the pool of patients who would find marijuana to be as or more useful than the invariably more toxic conventional drugs it will displace are allowed legal access to it. The framers of the New Jersey legislation may fear what they see as chaos in the distribution of medical marijuana in California and Colorado, a fear born of their concern that the more liberal parameters of medical use adopted in these states have allowed its access to many people who use it for other than strictly medicinal reasons. If this is correct, it is consistent with my view that it will be impossible to realize the full potential of this plant as a medicine, not to speak of the other ways it is useful, in the setting of this destructive prohibition. But this is rapidly changing as last year both Colorado and Washington repealed, as far as the state is concerned, the prohibition of cannabis for anyone over the age of 21.

In the United States we are gradually realizing after arresting over 24 million marijuana users since the 1960s, most of them young and 90% for mere possession, that "making war" against cannabis does not work anymore now than it did for alcohol during the days of the Volstead Act. Many people are expressing their impatience with the federal government's intransigence as it obdurately maintains its dual archaic positions that "marijuana is harmful" and that it "is not a medicine." The 23 states that have made it possible for at least some patients to use cannabis legally as a medicine are inadvertently constructing a large social experiment in how best to deal with the reinvention of the "cannabis as medicine" phenomenon, while at the same time sending a powerful message to the federal government. Each of these state actions has taken a slice out of the extraordinary popular delusion, cannabinophobia.

Cannabinopathic medicine, because it has developed so rapidly since the late 90s, has provided many patients and the people to whom they matter the opportunity to discover for themselves that cannabis is both relatively benign and remarkably useful. This new increment of people who have personal experience with cannabis may be contributing significantly to the observation that the moral consensus about the evil of marijuana is becoming uncertain and shallow. Conservative authorities pretend that eliminating cannabis traffic is like eliminating slavery or piracy, or eradicating smallpox or malaria. The official view, at least as far as the federal government is concerned, is that everything possible has to be done to prevent everyone from ever using marihuana, even as a medicine. But there is also an informal lore of marihuana use that is far more tolerant. Many of the millions of cannabis users around the world not only disobey the drug laws but feel a principled lack of respect for them. They do not conceal their bitter resentment of laws that render them criminals. They believe that many people have been deceived by their governments, and they have come to doubt that the "authorities" understand much about either the deleterious or the useful properties of the drug. This undercurrent of ambivalence and resistance in public attitudes towards marijuana laws leaves room for the possibility of change, especially since the costs of prohibition are all so high and rising.

It is also clear that the realities of human need are incompatible with the demand for a legally enforceable distinction between medicine and all other uses of cannabis. Marijuana simply does not conform to the conceptual boundaries established by twentieth-century institutions. It is truly a sui generis substance; is there another relatively non-toxic drug which is capable of heightening many pleasures, has a large and growing number of medical uses and has the potential to enhance some individual capacities? The only workable way of realizing the full potential of this remarkable substance, including its full medical potential, is to free it from the present dual set of regulations – those that control prescription drugs in general and the special criminal laws that control psychoactive substances. These mutually reinforcing laws establish a set of social categories that strangle its uniquely multifaceted potential. The only way out is to cut the knot by giving marijuana the same status as alcohol – legalizing it for adults for all uses and removing it entirely from the medical and criminal control systems.

Before closing, I would like to reassure those who believe we do not yet know enough about marijuana to be able to make the kinds of decisions which are now necessary. Despite the US government’s three-quarter century-long prohibition of marijuana and its confinement to Schedule 1 of the Drug Control and Abuse Act of 1970, it is nonetheless one of the most studied therapeutically active substances in history. To date, there are over 20,000 published studies or reviews in the scientific literature referencing the cannabis plant and its cannabinoids, nearly half of which were published within the last five years according to a keyword search on PubMed Central. Over 1,400 peer-reviewed papers were published in 2013 alone. By contrast, a keyword search of “hydrocodone” yields just over 600 total references in the entire body of the available scientific literature. These studies reveal that marijuana and its active constituents, the cannabinoids, are safe and effective therapeutic and/or recreational compounds. Unlike alcohol and most prescription or over-the-counter medications, cannabinoids are virtually non-toxic to the health of cells and organs, and they are incapable of causing the user to experience a fatal overdose and unlike opiates or ethanol, cannabinoids are not central nervous system depressants and cannot cause respiratory failure. In fact, a 2008 meta–analysis published in the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association reported that cannabis-based drugs were associated with virtually no elevated incidences of serious adverse side-effects in over 30 years of investigative use.

It is now clear that we know as much or more about cannabis than we know about many if not most prescription pharmaceuticals. And we most certainly now know enough about its limited toxicity and remarkable medical potential to readmit it as a significant contribution to the pharmacopeia of allopathic (or modern Western) medicine.

Lester Grinspoon, M.D. is, associate professor emeritus of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He served for 40 years as senior psychiatrist at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Boston and was the founding editor of both the Annual Review of Psychiatry and the Harvard Mental Health Letter. Dr. Grinspoon is a fellow of both the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Psychiatric Association.

Can we afford another Big Tobacco?

by Kevin Sabet, Ph.D.

Proponents of legalization and other drug policy reforms make some important points. It is true that most people who try drugs will stop after using a few times and not become addicted. It is also true – and regrettable –that America’s incarceration rate in embarrassingly high and has racially disproportionate effects. Also true – and encouraging – is that science is revealing many promising therapeutic uses for marijuana and its components.

But none of those realities is a good argument for legalizing marijuana.

Medical Marijuana

Medical marijuana is a vexing issue for most of us. No one wants to see his or her loved ones suffer. But the issue often becomes overcomplicated. Indeed, research shows that like opium, marijuana has medicinal value. THC, marijuana’s active ingredient, has been shown to help appetite and pain. Other components of marijuana, like CBD, seem to be promising for things like epileptic seizures or spasticity due to MS. There are likely other promising applications around the corner.

That marijuana has medicinal value, however, is no argument for legalizing the raw plant – either de facto or de jure. We wouldn’t ask people to smoke opium to receive Morphine’s benefits, or chew willow bark to receive Aspirin’s effects.

Most would agree that if marijuana has medicinal benefits, we should standardize a dose (that means smoking the drug is not possible) and make it available at pharmacies.

Many would also likely agree that whatever we do with medical marijuana, we shouldn’t make it a front for legalization. Sadly, in states that voted for marijuana as a medicine, however, that is exactly what is happening. In California, for example, the vast majority of medical marijuana card holders are men in their 30s and 40s with back pain. AIDS, MS, Cancer and other serious illnesses make up fewer than 2% of all cardholders. Numbers are similar across other states.

Legalizing it?

America is currently being sold a false dichotomy: “You can either stick with failed, current policies, or you can try a ‘new approach’ with legalization and regulation.” Sadly, this kind of black and white thinking betrays the fact that there are better ways than legalization or prohibition to deal with this complex issue. I argue here why legalization, especially, is undesirable.

Marijuana legalization is no longer about a few friends calmly sharing a joint on the weekend in their own living room. Inevitably – and ever so swiftly – it has become about big business and big bucks.

For example, with much fanfare, and alongside the ex-President of Mexico Vicente Fox, former head of Microsoft corporate strategy James Shivley announced this year that he was creating “the Starbucks of marijuana.” His plan? To buy up marijuana stores in Colorado and Washington state, “mint[ing] more millionaires than Microsoft in this business.” Mr. Shivley isn’t the only one preparing to cash in. At least three marijuana vending machine companies, already earning millions of dollars in revenue from medical marijuana “patients,” have announced giant expansion plans. “It is like a gold rush,” remarked one vending executive. A couple of Yale MBAs recently created a multi-million dollar private equity firm dedicated solely to financing the marijuana business. As one of them explains, the firm has become inundated with pitches from businesses who plan to become the “Wal-Mart of marijuana.”

And so, in the midst of America’s great debate about marijuana legalization, Big Marijuana is born.

To a student of history, none of this should come as a surprise, of course. Tobacco executives in the 1900s wrote the playbook on the reckless and deceitful marketing of an addictive – and therefore hugely profitable – substance. We’ve seen this horror movie before.

We also know that addictive industries generate the lion’s share of their profits from addicts, not casual users. In the tobacco industry, 80 percent of the industry’s profits come from 20 percent smokers. So while most marijuana users try the drug and stop, or use very occasionally, and the brunt of the profits – and problems – come from the minority of users, that minority causes enormous problems to our roadways, educational system, workplace, and health care system.

This means that creating addicts is the central goal. And – as every good tobacco executive knows (but won’t tell you) – this, in turn, means targeting the young. When people start tobacco or marijuana use during the period of youth, when their brains are still developing, their chances of becoming addicted are far greater. Internal company memos released as result of the great tobacco settlement tell us as much: “Less than 1/3 of smokers start after age 18,” says one, and “If our company is to survive and prosper, we must get our share of the youth market…[That] will require new brands tailored to the youth market.” Such memos were circulated even as the tobacco industry was publicly rejecting youth cigarette use. And now, companies like Japan Tobacco International and 22nd Century Tobacco Group have invested in marijuana businesses.

The poor and otherwise vulnerable are also prime targets. They suffer the highest addiction rates of any group. It’s no wonder that peer reviewed research has concluded that tobacco and liquor outlets are several times more likely to be in poorer communities of color, and that the tobacco industry has cozied up with homeless shelters and advocacy groups as part of its “downscale” marketing strategy. The former Winston man, now suffering from smoking-related illnesses, testified: “Of course children aren’t the only targets…Once, when I asked an R.J. Reynolds executive why he didn’t smoke, he replied, ‘We don’t smoke this sh*t. We reserve that right for the young, the poor, the black, and the stupid.’”

Rejecting legalization does not mean we have to be content with the status quo. We need much better, science based prevention, early intervention, and treatment. We need to make sure our laws are equitable and fair. Specifically, even as marijuana remains illegal, low-level marijuana offenses should not saddle people with a criminal record that hurts their chances at education, housing or other assistance. Drug treatment courts and smart probation programs must also be taken to scale.

But under legalization, big business and big lobbies pedal pseudoscience and stop at nothing to protect their profits. Before it was ordered to disband due to deceitful practices, “Tobacco Institute, Inc.” was the industry’s lobby group, challenging studies linking smoking with cancer and rebutting Surgeon General reports on cigarettes before they were even published. Today, Big Tobacco still has a powerful presence in Washington. It fights any safety measures that might curb cigarette use and ensures that federal cigarette taxes remain low (to bring federal cigarette taxes back to their inflation adjusted level in 1960, we'd have to see a 17% increase in tobacco taxes today).

We can fully expect marijuana profiteers to recycle the tactics that have earned Big Tobacco billions and billions of dollars. Already, the claims made by Big Tobacco only a few decades ago are being revived by the new marijuana moguls: “Moderate marijuana use can be healthy.” “Marijuana-laced candy is meant only for adults.” “Smoked marijuana is medicine.”

It is true that marijuana is not as addictive as tobacco cigarettes (in fact, tobacco is more addictive than even heroin). And marijuana and tobacco differ among other dimensions of harm. Tobacco, though deadly, does not get one high, and so unlike marijuana, one can drive impairment-free while smoking tobacco. That means that when someone is high, their ability to learn, work, and become an active member of society is threatened. That is the last thing young people need today as they try to get a quality job or education.

Indeed, there is a reason that education and public health professionals, including groups like the American Medical Association, National School Nurses Association, American Society of Addiction Medicine, American Psychiatric Association, American Pediatrics Association, and the American Lung Association oppose legalization and regard today’s high potency marijuana as harmful. Today’s marijuana is not the marijuana of the 1960s, with potency more than tripling in the last fifteen years. High-potency marijuana has contributed to addiction for 1 out of every 6 kids who ever use marijuana, direct IQ loss (an 8 point loss among kids using regularly), car crashes, and mental illness. This is not reefer madness thinking: kids go to treatment for marijuana problems more than they do for all drugs (including alcohol) combined. Can we afford decades of deceit from an industry that depends on addiction and heavy use for profits…all over again?

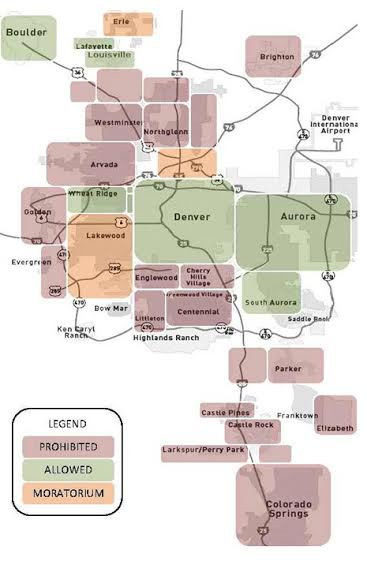

Some say that it doesn’t have to be this way. We could establish a safer form of legalization by setting up measures that prevent the emergence of another Big Tobacco. History and experience show, however, that even the best of intentions are easily mowed over in the name of big profits. This will be American-style legalization. Unless we repeal the First Amendment –which declares commercial speech as free speech – and unless we quickly do away with our longstanding Madison Avenue culture of hyper-commercialization, legal marijuana will lead down an all-too-familiar path. We are seeing this play out in Colorado with abandon. Already, deaths have been attributed to marijuana edibles, and an ever-powerful industry is flexing its muscle. Advertisements for marijuana are everywhere and industry lobbyists are strong-arming small city councils for “friendlier” business regulations. Even so, tax revenue has fallen short— less than a third of the projected amount has been raised.[i] Currently, the marijuana use rate among Colorado teens is 50% above the national average[ii] and youth use has been on the rise since marijuana was first commercialized and sold in stores (as medicine to anyone over 18 with a headache!) in 2009. Drug-related referrals for high school students testing positive for marijuana has increased[iii] and peer-reviewed research has found medical marijuana is easily diverted to youth.[iv] And while the total number of car crashes declined from 2007 to 2011, the number of fatal car crashes with drivers testing positive for marijuana rose sharply.[v] Two people have died due directly to recreational marijuana being openly sold since January, and the poison center calls due to kids accidentally ingesting “edibles” are mounting. Things are hardly going well. And it looks like Coloradans may be noticing: two recent polls show a major slip in support for legalization. A USA Today/Suffolk University poll in Colorado shows now that only 46% of Coloradans agree with legalization—that is a 17% difference from the 55% of voters that approved their referendum in 2012. And a national poll of over 4,500 adults funded by the Ford Foundation found that there has been a 14% reduction since 2013 in the percentage of all adults in favor of legalization – it now stands at 44% support. Finally, most localities still have not allowed marijuana stores in their community (see map, Figure 1). Buyers remorse may, indeed, be happening because of the public health crisis brewing in Colorado.

Figure 1: Legal status of marijuana stores in the Denver, CO area

But, of course, some people are benefiting from this new policy — the Yale MBAs, the established addictive industries, and the new Mad Men of marijuana.

We should stop them in their tracks while we still can.

Kevin Sabet, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of psychiatry, and Director of the Drug Policy Institute at the University of Florida and previously served in the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. He founded Project SAM (Smart Approaches to Marijuana) with Patrick J. Kennedy in 2013.

[i] Tax Revenue Falls Short: http://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/local-news/tax-revenue-from-recreational-pot-sales-in-colorado-fall-short-of-estimates08132014

[ii] NSDUH, Summary of National Findings, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.pdf

[iii] Rocky Mountain HIDTA. (2014). Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact. Retrieved from http://www.rmhidta.org/html/FINAL%20Legalization%20of%20MJ%20in%20Colorado%20The%20Impact.pdf

[iv] Salomonsen-Sautel, S., et al. (2012). Medical marijuana use among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Journal of American Academic Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(7).

[v] Rocky Mountain HIDTA. (2013). Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact. Retrieved from http://www.rmhidta.org/html/FINAL%20Legalization%20of%20MJ%20in%20Colorado%20The%20Impact.pdf

Brass Knuckles Vape September 18, 2018

Well, Legalization is good. Thank you so much for this information, Its really helpful for people. Marijuana is helpful for cancer treatment.

Jennifer Smith December 30, 2018

Even if there are opposing viewpoints about cannabis legalization, I am glad there’s progress now that cannabis has been legalized in Canada. Great post!

Kevin Murphy July 28, 2019

Medical and other literature with the goal of providing a reasonably objective summary of the data which underlay its prohibition but at this time marijuana can do much good than do something bad.

Athea Jo August 5, 2019

I am a pro-cannabis advocate. I’m glad that the cannabis industry has progressed now that other states and countries like Canada have legalized it.

Dan Collins January 3, 2021

There are really important things to consider before legalizing marijuana in some states. I learned a lot from this post. Thank you so much for sharing this.