The chronically homeless, especially those with substance use problems, represent a tremendous cost to states’ public health care, criminal justice, and other social welfare systems. Abstinence-based housing programs do not always prove effective in dealing with this population sector and sometimes fail to prevent substance abuse relapses (Culhane & Metraux, 2008). This week’s DRAM reviews a study about the cost-effectiveness of a housing program, Housing First, which does not require sobriety, allowing residents to drink in their rooms while still receiving food, shelter, healthcare, and substance abuse counseling (Larimer et al. 2009).

Methods

- Researchers recruited participants by rank-ordering a list of known chronically homeless people by their total monthly costs to public services in 2004. Housing First’s staff offered housing to these individuals in order on a first come first serve basis. Ninety-five individuals received housing (n=95; housed); the remaining willing participants were placed on a wait-list (n=39; controls).

- Researchers estimated average monthly costs by collecting data from participants including: jail days, jail bookings, shelter nights, EMS contacts, detoxification days, sobering center visits and Medicaid charges.

- Interviewers administered the Current Substance Use Assessment of the Addiction Severity Index to all participants at baseline, three, six, nine, and twelve months after the study began.

Results

- Regression analyses revealed that housed participants incurred significantly fewer costs (53% less) than the controls during the first six months of the study.

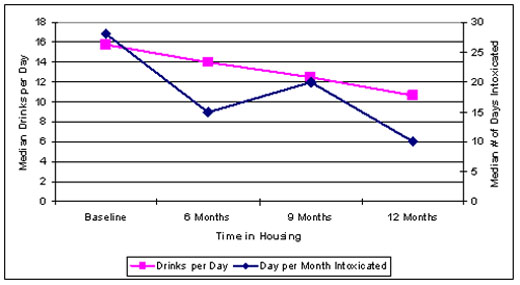

- Housed participants also showed a significant decrease in average number of daily drinks and average number of days intoxicated (see Figure).

Figure. Median number of drinks per day and days per month spent intoxicated at baseline, six, nine and twelve months after housing intervention (adapted from Larimer et al. 2009). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- Participants were not randomly assigned to the experimental or control conditions.

- Researchers did not compare the results from this study to the results from an abstinence based program.

- Researchers used self report measures and interviews to obtain alcohol abuse data.

- Not all of the participants completed the study.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations and need for further research, the study suggests that providing housing (without requiring substance abstinence) to chronically homeless individuals with alcohol abuse problems not only decreases their monthly cost to the public system, but might also contribute to the individuals’ alcohol addiction recovery.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Culhane, D. P., & Metraux, S. (2008). Rearranging the deck chairs or reallocating the lifeboats? homelessness assistance and its alternatives. JAMA, 74(1), 111-121.

Larimer, M., Garner, M. D., Atkins, D. C., Burlingham, B., Lonczak, H. S., Tanzer, K., et al. (2009). Health Care and Public Service Use and Costs Before and After Provision of Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons With Severe Alcohol Problems. JAMA, 301(13), 1349-1357.

WolfBandiT May 4, 2009

Its about time that people figured out the more you tell someone to stop a certain behavior, the more likely they will continue that behavior in tenfold, just to defy the system.