If exposure to gambling contributes to the development of addiction, then more exposure should correspond to higher rates of gambling problems (Shaffer et al., 2004). This week we examine a study of highly exposed people – those living near a casino – to determine whether their rates of gambling are different from those living farther from a casino (Sevigny, Ladouceur, Jacques, & Cantinotti, 2008).

Participants:

Random sample of 4,922 people drawn from an area within 100km of a Montreal casino.

Methods:

Household telephone survey (Ladouceur, Jacques, Chevalier, Sevigny, & Hamel, 2005)

Measures:

- Driving distance from casino (participants were divided into 5 groups: those who lived 0-20km, 20-40km, 40-60km, 60-80km, and 80-100km away from a casino)

- Casino visits in the past year

- Gambling problems as measured by the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987)

- Self reported income

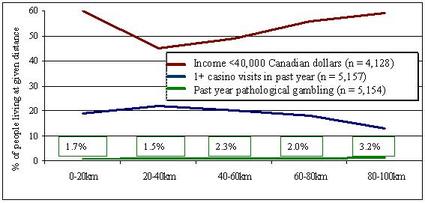

Figure 1: Casino participation, prevalence of pathological gambling, and income in last 12 months by distance to nearest casino (adapted from Sevigny et al., 2008).

Results:

People who lived closest to the casino were:

- Just as likely to be pathological gamblers as the rest of the sample,

- More likely than those living furthest away to have visited the casino during the past year, and

- No more likely than those living furthest away to have lower incomes.

Limitations:

- Proximity to a casino might not be a comprehensive measure of exposure because the casino represents only one gambling venue; other gambling opportunities, such as lotteries, are distributed throughout all regions.

- Proximity to a casino is arbitrarily set at discrete (20km) intervals; this might not represent distance accurately (a continuous measure).

- Self report methodology

Conclusion:

The relationship between exposure and gambling problems is complex, involving the influence of other variables. For example, individual or regional vulnerability could moderate the relationship between exposure and gambling disorders. Future studies could measure interactions between exposure variables and vulnerability variables (e.g., local crime levels and gambling policies, individual mental health and family gambling practices), and the interactions’ effects on the exposure-related development of gambling problems.

For more WAGER articles about exposure, please see:

The WAGER Vol. 9(16) – Regional Index of Gambling Exposure – An Acid Test

The WAGER Vol. 10(10) – Risky Business: Youth Gambling

The WAGER Vol. 10(1) – Addiction as Syndrome

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Leslie Bosworth

References

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen: A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184-1188.

Sevigny, S., Ladouceur, R., Jacques, C., & Cantinotti, M. (2008). Links between casino proximity and gambling participation, expenditure, and pathology. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(2), 295-301.

Melvin April 28, 2016

The article on living close to casino with no real effect is simply not true. Most of my criminal cases as a result of gambling addiction came about when casino play became more available by being close to client.

The BASIS Staff April 28, 2016

Thank you for your interest and response to this post. In your correspondence, you wrote that you noticed that more criminal cases related to gambling occurred when casino play became more accessible; therefore, the findings of Sevigny’s study were false.

Sevigny, Ladouceur, Jacques, & Cantinotti’s 2008 study reports trends – that is, what is true for most people. They aggregated data from many individuals and report about the trends across the individuals included in the sample. For any given individual, the trend they report might not apply. Their study tells us whether, in general, there is a systematic relationship between exposure and gambling problems that exceeds chance. Therefore, the report lacks information about each individual’s experience. On the other hand, your evidence base is case oriented. Ultimately, cases are anecdotal evidence and do not necessarily represent the population.

Thus, there is a divide between clinicians’ experience with individuals and scientists’ experience with groups. The well-known Berkson’s bias (1946) is but one example of this divide. One way research in this area can bridge this divide is to identify for whom casino exposure results in problems and why.

Another consideration in clarifying the relationship between casino exposure and gambling problems is the length of time your criminal cases were exposed to casino games versus how long participants in the Sevigny et al. study were exposed. Your letter implies gambling problems arose soon after the introduction of casino games; Sevigny et al.’s participants were exposed to a casino for ten years before they were surveyed. We have reported previously that people appear to adapt to the presence of the casino (LaPlante, D.A. & Shaffer, H. J. (2007). Understanding the influence of gambling opportunities: Expanding exposure models to include adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 616-623). Gambling-related problems that might be similar to those of your clients tend to happen most when the casino gambling opportunity is new. As the novelty effect wears off, however, people adapt and fewer have gambling related problems.

Identifying these complex issues and the broad research base associated with addictive behaviors is one of the main reasons why we write the BASIS and encourage feedback from readers.

Again thank you for your interest in the BASIS and for your comments. We always appreciate feedback, questions, and comments from readers.

-The BASIS Staff

References

LaPlante, D.A. & Shaffer, H. J. (2007). Understanding the influence of gambling opportunities: Expanding exposure models to include adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 616-623.

Berkson’s bias is detailed in Berkson, J. (1946). Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics, 2, 47-53.