Researchers have linked exposure to childhood sexual abuse (CSA), with or without post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, to higher prevalence rates of cigarette smoking compared to the general population (e.g., Al Mamun Alati, O’Callaghan, Hayatbakhsh, O’Callaghan, et al. 2007). This association suggests a causal link between CSA and subsequent risk for regular smoking. However, if CSA were truly a “cause” of smoking, then people who experienced more CSA incidents would be more likely to smoke than people who experienced fewer CSA incidents. This week’s ASHES examines data from a nationally representative sample of adolescents and young adults to determine whether young adults who experienced multiple incidences of CSA were more likely to smoke regularly than those with just one incident.

Roberts, Fuemmeler, McClernon, and Beckham (2008) analyzed data from the most recent wave of the Add Health dataset, when participants were about 22 years old. After exclusions (e.g., pregnant women who would be less likely to smoke) and attrition, the authors included 67.2% (n=13,943) of the original population. Researchers defined ever-regular smokers as those who smoked at least one cigarette every day for at least 30 days after the sixth grade. Participants met study criteria for CSA if they endorsed being “forced to engage in sexual relations with an adult caregiver” before the sixth grade. Participants also retrospectively self reported the number of times this type of trauma occurred.

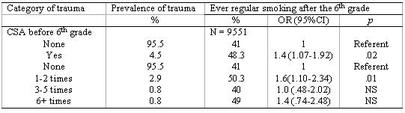

Figure. Percentage and adjusted odds ratio of onset of lifetime ever-regular smokers by CSA. Click image to enlarge.

Note: CSA = Childhood sexual assault; CI = Confidence interval; NS = Not significant; OR = Odds ratio. Models adjusted for age, race, gender, highest level of education, depressive symptoms, and parent smoking. Adapted from Roberts et al. (2008).

Of the total sample, 38.6% reported ever-regular smoking. About 5% (4.5%) of the total sample reported CSA before the sixth grade. The Figure shows that among those reporting CSA as compared to the rest of the sample smoking rates were elevated. Having reported one CSA incident significantly increased the odds of smoking; additional incidents did not change the risk.

Rates of both CSA and smoking might not be accurate. Almost one third of the original population did not participate in this most recent analysis; those lost to attrition might have been more likely to have experienced CSA or to have smoked. Researchers defined CSA narrowly: more than just caregivers can initiate sexual assaults; sexual assaults can occur after the 6th grade; and not all who experienced CSA remember the abuse as seeming forced at the time. Some respondents might not report a traumatic experience such as CSA, and others might not accurately remember whether it happened or how many times. Therefore CSA rates are likely higher than reported in this study.

The severity of CSA is not a robust a predictor of smoking as having experienced any CSA at all. Further study is necessary to determine what factors mediate adverse behavioral outcomes of trauma. Specifically, investigating differences in coping styles between people who experience one incident of CSA versus those who experience multiple incidences might shed light on factors that mediate risk for smoking.

–Leslie Bosworth

References

Al Mamun, A., Alati, R., O’Callaghan, M., Hayatbakhsh, M. R., O’Callaghan, F. V., Najman, J. M., et al. (2007). Does childhood sexual abuse have an effect on young adults’ nicotine disorder (dependence or withdrawal)? Evidence from a birth cohort study. Addiction, 102, 647-654.

Roberts, M. E., Fuemmeler, B. F., McClernon, F. J., & Beckham, J. C. (2008). Association between trauma exposure and smoking in a population-based sample of young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42, 266-274.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.