Research demonstrates that high levels of cigarette smoking are associated with an increased risk of panic attack, panic disorder, and agoraphobia (i.e., panic spectrum psychopathology, Breslau & Klein, 1999; Breslau, Novak, & Kessler, 2004; McLeish, Zvolensky, & Bucossi, 2007). Researchers suggest anxiety sensitivity (AS), “the fear of arousal-related physical and psychological sensations” (McLeish, Zvolensky, Yartz, & Leyro, 2008), encourages the development of panic-spectrum psychopathology and other anxiety disorders (Reiss & McNally, 1985). ASHES Vol. 4(3) illustrated Zvolensky and Bernstein’s (2005) integrative model relating smoking and panic disorder. This week’s ASHES reviews a study that examined the effects of the Physical Concerns domain of AS on the relationship between smoking status and anxiety symptoms and body vigilance (i.e., attention to physical symptoms).

McLeish, Zvolensky, Yartz, and Leyro (2008) recruited 222 young adults from local communities in Vermont, approximately half of whom were current smokers. Trained research assistants interviewed all participants using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Non-Patient Edition. All participants then completed the Smoking History Questionnaire, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Anxiety Sensitivity Index, Body Vigilance Scale, and Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire. The researchers hypothesized that the Physical Concerns domain of AS would influence the relationship between smoking status and body vigilance and anxiety symptoms, such that increased AS Physical concerns would correlate with increased panic symptoms (i.e., anxiety symptoms, body vigilance) among smokers.

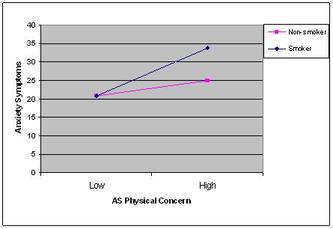

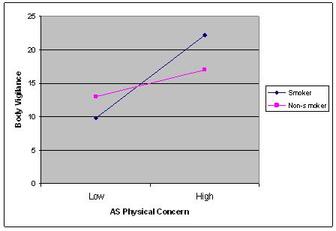

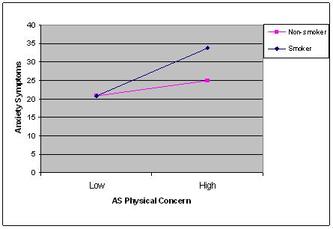

McLeish et al. (2008) used a hierarchical multiple regression procedure to assess the interactive effects of smoking status and AS Physical Concerns for body vigilance and anxiety symptoms, controlling for gender and alcohol use disorders. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate that the direction and significance of the interactions were as the researchers predicted: increased AS Physical Concerns and positive smoking status predicted elevated anxiety symptoms (t=3.04, β=.27, p<.01; Figure 1) and body vigilance (t=2.26, β=.23, p<.05; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Anxiety symptoms as a function of AS Physical Concerns and smoking status (McLeish et al., 2008). Click image to enlarge.

Figure 2. Body Vigilance as a function of AS Physical Concerns and smoking status (McLeish et al., 2008). Click image to enlarge.

This study is not without limitations. Although the racial composition of the participants reflected that of the local communities (94% Caucasian, 2% African-American, 1% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% other), the results might not be applicable to regions with a more diverse or different distribution of races. Moreover, the number of college students who participated was greater than that of participants from other sections of the community. Further, few of the college students were “heavy” smokers. Subsequently, the self-selection bias of this particular group might have influenced the results. Other limitations include the use of self-report measures and not controlling for participants’ use of other substances.

The findings of this study should be helpful to those providing support for current smokers. Specifically, if clinicians are able to identify the smokers who are most likely to experience anxiety related to physical concerns, they can initiate specialized intervention and prevention programs to limit these concerns. Helping these smokers to understand the increase in physiological arousal that can accompany smoking withdrawal could ease their anxiety symptoms and increase the likelihood of their quitting successfully.

–Sara Kaplan.

References

Breslau, N., & Klein, D. F. (1999). Smoking and panic attacks: An epidemiologic investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 1141-1147.

Breslau, N., Novak, S. P., & Kessler, R. C. (2004). Daily smoking and the subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders. Psychological Medicine 34, 323-333.

McLeish, A. C., Zvolensky, M. J., & Bucossi, M. M. (2007). Interaction between smoking rate and anxiety sensitivity: Relation to anticipatory anxiety and panic-relevant avoidance among daily smokers. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 849-859.

McLeish, A. C., Zvolensky, M. J., Yartz, A. R., & Leyro, T. M. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity as a moderator of the association between smoking status and anxiety symptoms and body vigilance: Replication and extension in a young adult sample. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 315-327.

Reiss, S., & McNally, R. J. (1985). Expectancy model of fear. In S. Reiss & R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy (pp. 107-121). San Diego: Academic Press.

Zvolensky, M. J., & Bernstein, A. (2005). Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14(6), 301-305.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

loysten June 18, 2008

To Sara Kaplan,

Nowadays smoking has become a problem to the country and the world.

Using an integrative model will definitely help to calm our nerves in smoking. But the thing is it takes time.