Clinicians have identified nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), such as nicotine gum, patches, and lozenges, as one of the most cost-effective, life-preserving interventions available to medical science (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002; Silagy, 2004). However, many smokers might use NRT sub-optimally, leading to a lower level of efficacy outside of clinical trials. This week’s ASHES reports on a multinational cohort study testing the effectiveness of NRT as a smoking cessation tool in the ‘real world’.

West & Zhou (2007) used the Internet to recruit participants who smoked five or more cigarettes per day, were 35 to 65 years old, and intended to quit. Researchers sent an email invitation to complete a 25-minute online survey three and six months after participants initiated a quit attempt (West et al, 2006). This follow-up measure assessed continuous abstinence since the previous assessment, methods used to quit, and nicotine dependence.

Of the 1561 smokers from five countries who had made a quit attempt, 1089 (69.8%) were followed three and six months later. Of these, 344 (31.6%) used NRT and 745 (68.4%) did not. The success rate of those using NRT was 7.8%, and of those not using NRT was 4.0%. The odds of achieving six months of abstinence, adjusted for nicotine dependence, among those using NRT were 2.2 times higher than those not using NRT.

Limitations of the study include the fact that the sample was recruited using the Internet. Individuals seeking smoking information on the Internet might not be representative of ‘real world’ smokers attempting to quit. Self-reported quit rates could be another source of bias, but there is no reason to assume it would contribute to a difference in success rates as a function of NRT use versus non-NRT use.

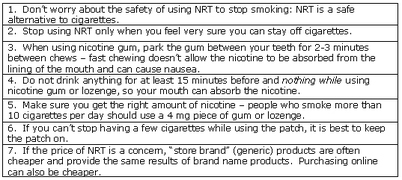

Figure. Advice for the Effective Use of Nicotine Replacement Therapies (adapted from Kozlowski et al (2007)) Click image to enlarge.

This study supports the findings of clinical trials suggesting that NRT use is associated with improved chances of long-term abstinence when used by smokers attempting to quit in the ‘real world’. To ensure the effectiveness of NRT, these medications should be used properly; Table 1 provides information about correct NRT use. Further research should be conducted to determine if certain nicotine replacement therapies are more effective than others.

–Andrew Boudreau.

References

Kozlowski, L., Giovino, G., Edwards, B., DiFranza, J., Foulds, J., Hurt, R., et al. (2007). Advice on using over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy – patch, gum, or lozenge – to quit smoking. Addictive Behaviors.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2002). National Institute for Clinical Excellence Technology Appraisal Guidance No. 38 Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and bupropion for smoking cessation.

Silagy, C., Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, & Fowler G. (2004). Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3.

West, R., Gilsenan, A., Coste, F., Zhou, X., Brouard, R., Nonnemaker, J, et al. (2006). The ATTEMPT cohort: a multi-national longitudinal study of predictors, patterns and consequences of smoking cessation; introduction and evaluation of internet recruitment data collection methods. Addiction, 101(9), 1352-1361.

West, R., Zhou, X. . (2007). Is nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation effective in the “real world”? Findings from a prospective multinational cohort study. Thorax Online First.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.