The start of college can be a challenge for freshman. Incoming students encounter new environments, friends, and lifestyles. Students also might have first-time contact or increased access to new experiences, such as the use of alcohol and drugs. Because college students face few restrictions, these new experiences place them at increased risk for alcohol problems. Over 80% of college students report drinking alcohol and almost 50% of college students report binge drinking (Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994). Findings like these have prompted researchers to look at what influences students’ drinking and how substance use is regulated on campuses. Shaffer, Donato, LaBrie, Kidman, and LaPlante (2005) conducted the first national study of drinking- and gambling-related policymaking on college campuses, aiming to encourage the development of science-guided school policy. This week’s DRAM reviews the research, which found that while there are some commonalities to college policies, colleges often take very different approaches to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems.

The study examined the alcohol and gambling policies published in the student handbooks, websites, and supplementary materials of 117 scientifically selected colleges (the same sample used in the 2001 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study). Researchers collected 164 documents in total and assigned 11 coders the job of examining each school’s policies. Certain policies were collapsed into the primary items from which they originated (e. g., “alcohol is prohibited on-campus for students <21” and “on-campus alcohol restrictions in place for students ≥21” were both included in “policy on alcohol use on-campus for students ≥21” ). After collapsing the redundant policy items, 22 alcohol policy variables remained. Raters decided whether schools indicated that they had policies relevant to the defined topics, such as content and target.

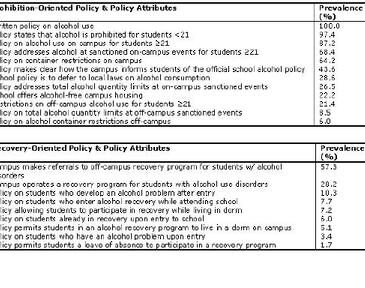

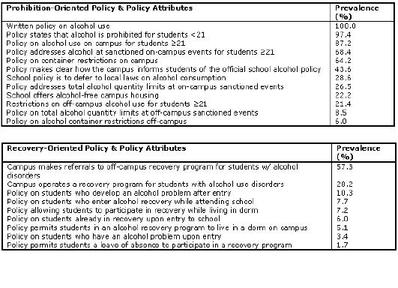

The authors found that most colleges have some type of prohibition policy (forbidding the use of substances). More than 97% of schools had a policy stating that alcohol is prohibited for students under 21 years old, more than 87% of schools had a policy on alcohol use on campus for students over 21 years old, and more than 64% of schools had a policy addressing alcohol container restrictions on-campus (Shaffer et al., 2005).

Recovery-oriented policies (focusing on treatment) were sufficiently identified among published policy at fewer than 30% of the schools (Shaffer et al., 2005). Less than 2% of schools had a published policy in place about using a leave of absence for recovery and less than 6% of schools had a published policy in place that would allow students to participate in recovery while living in the dorms. Less than 11% of schools had sufficiently identified published policies about students who develop an alcohol problem while in school, who already are in recovery upon entry to school, or who enter recovery while in school.

Figure. Prevalence of college alcohol policies and policy attributes (adapted from Shaffer et al., 2005). Click image to enlarge.

There were some methodological limitations to this study. Because the study only used information from policy materials that were sent by each school or that were publicly available, the researchers may have unintentionally omitted policy information from other policy materials, such as orientation information sessions or pamphlets. Further, the sample included only 117 colleges, while there are more than 630 public 4-year institutions and more than 1830 private 4-year institutions in the U.S. (Fact Monster, 2005). Another limitation is that this study examined policy in theory but not necessarily in practice. Schools may rely more on informal rules, case-by-case basis, and established precedents to regulate alcohol and substance use rather than enforce policy strictly “by the book.”

Alcohol and drug use on college campuses might be reduced if more recovery-oriented policies were established. This is an empirical question worthy of scientific investigation. By helping students with addictive behaviors recover and offering them a choice to change, colleges could help students with alcohol problems before serious consequences develop (e.g., academic difficulties, traumatic injuries, high-risk sexual behavior, and impaired driving).

Students and parents deciding on a school whose published policies are consonant with their concerns should look at college addiction policies and resources to make an informed decision. This information might be posted on the school website or published in the student handbook. Possible questions to consider include: if a student is inebriated and in potential medical danger, whether a friend can bring the student to a university health center for medical attention without risk of penalty or discipline; whether there are peer counselors available who have been trained in the areas of alcohol or substance abuse; and whether there is an early intervention program or protocol for students having alcohol or other substance problems.

—Bree Tse

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Fact Monster. (2005). Number of U.S. Colleges and Universities and Degrees Awarded. Retrieved January 19, 2006, from http://www.factmonster.com/ipka/A0908742.html

LaBrie, R. A., Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., & Wechsler, H. (2003). Correlates of college student gambling in the United States. Journal of America College Health, 52(2), 53-62.

Shaffer, H. J., Donato, A. N., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R. C., & LaPlante, D. A. (2005). The epidemiology of college alcohol and gambling policies. Harm Reduction Journal, 2(1).

Wechsler, H., Davenport, A., Dowdall, G., Moeykens, B., & Castillo, S. (1994). Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 272(21), 1672-1677.