Alcohol use and abuse are ongoing problems for college campuses across the United States (Wechsler et al., 2002). In response, many college campuses have implemented individually oriented educational programs and counseling to change this problem behavior pattern. Unfortunately, there is no empirical evidence that these individually-focused efforts are effective (Larimer & Cronce, 2002; Wechsler et al., 2003). As an alternative, some colleges are attempting to change their overall culture, with respect to alcohol and its predominance in the social lives of students. The “A Matter of Degree” (AMOD) program, for example, uses a community coalition model, combining strategies that address access and availability of alcohol, price, promotion and advertising to change: 1) alcohol-related policies and practices; 2) alcohol consumption and drinking norms: and, 3) binge drinking and alcohol-related harms. More information about the AMOD program is available at www.hsph.harvard.edu/amod. This week the DRAM will discuss a preliminary evaluation of the AMOD program (Weitzman, Nelson, Lee & Wechsler, 2004).

The current study examined 42 schools that participated in the 1993 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study (CAS) survey that had high proportions of students who binge-drank. Ten schools, selected for their willingness to participate and dedication to the intervention, implemented the AMOD program in cooperation with community stakeholders. Consistent with the AMOD community coalition model, a team of experts at each site developed interventions specific to the community’s available resources and concerns. The remaining 32 schools did not implement an AMOD program, but participated in subsequent CAS surveys (225 undergraduate students were randomly selected to receive the survey every two years); these schools served as a comparison group. Each of the 10 AMOD schools randomly selected 750 undergraduate students to be surveyed between 1997 and 2001. Outcomes of interest included alcohol consumption, alcohol related harms, secondhand effect of alcohol consumption, and access to alcohol. The researchers examined the trend in outcomes for the 10 intervention schools overall and for the AMOD schools divided equally into groups defined by the researchers as exhibiting either a high or low level of implementation (i.e., number of interventions and ability of interventions to address the environment).

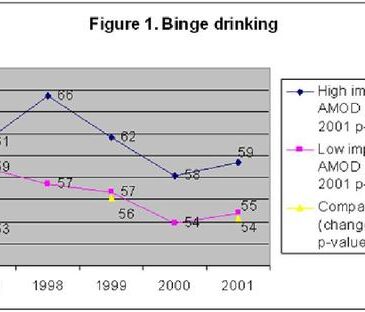

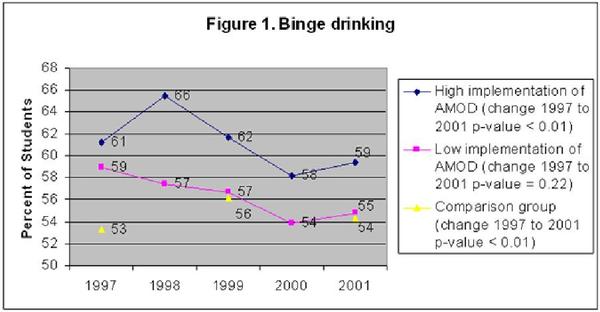

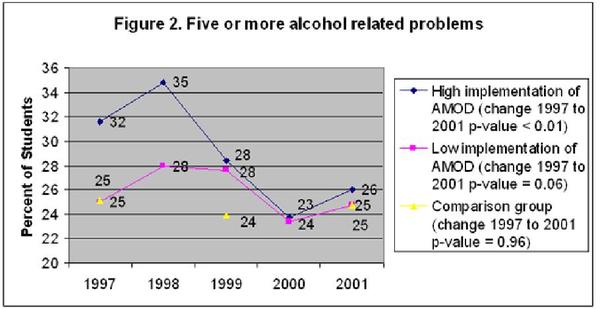

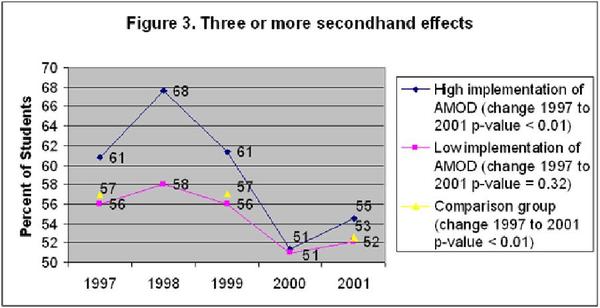

Although there were no consistent declines in outcomes for the 10 implementation schools overall compared the 32 schools without the intervention, the five schools with high implementation of the AMOD program showed significant decreases in multiple measures of alcohol consumption, alcohol related harms and secondhand effects from 1997 to 2001. Figures 1 – 3 summarize some of these findings. Schools with higher levels of drinking and negative drinking consequences at the beginning of the study were more likely to put AMOD fully into practice. In addition, the schools with more interventions showed the greatest reduction in negative drinking-related outcomes. This decrease might be analogous to monitoring weight loss among a group of dieters: the dieters who are the most overweight and follow the strictest dieting plan tend to show more dramatic weight loss at the beginning of the diet than dieters who are less overweight and do not follow the strictest dieting plan. Results from other large scale public health efforts, such as efforts to reduce driving under the influence, have shown that it can take decades before dramatic improvements in behavior patterns are realized (see BASIS editorial 1/12/05). Considering the short period of time the AMOD program was implemented, the findings from the current evaluation study are promising.

Figure. Click image to enlarge.

The investigators acknowledge that the current study has several limitations. Since implementation of the AMOD program was based on a self-selected sample rather than a randomized sample, it is difficult to determine the precise cause of change. Additionally, the small number of AMOD schools and limited observations over time for comparison schools might limit the precision of findings and the ability to detect significant changes in drinking-related behaviors over the study period. Since the 5 high implementation schools had higher starting points for many of the outcome measures, it is possible that risky drinking behaviors for these schools would have declined even without the intervention. In statistics, the tendency of extreme values to become less extreme (closer to the average) when they are reassessed is referred to as “regression to the mean.” Findings may also be subject to response bias since the measures were based on self-report surveys and there may have been greater pressure at AMOD schools to underreport risky drinking behaviors. It is also worth noting that the high implementation schools actually showed a slight increase in problems during 1998. The significance of change over time might be attributable to a retreat from the increased problems during 1998 rather than a decrease from 1997 to 2001.

Changing social norms for drinking behavior of college students is especially challenging. College students confront intense peer pressure and stress in their everyday lives; these forces can encourage them to engage in unhealthy drinking behavior. It will be interesting to see developments and evaluations of the AMOD program in the future. As strategies of proven effectiveness are identified, researchers will be able to randomly assign these interventions to a larger number of college campuses, permitting more accurate testing of the efficacy and impact of this innovative intervention strategy.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1. The authors conducted a sensitivity analysis which suggested that no single school drove the observed declines in the outcomes of interest.

2. Tests of significance measure trends for each group separately rather than differences between groups over time.

References

Larimer, M. E., & Cronce, J. M. (2002). Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol (Supplement 14), 148-163.

Wechsler, H., Lee, J. E., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Nelson, T. F., & Lee, H. (2002). Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. Journal of American College Health, 50(5), 203-217.

Wechsler, H., Nelson, T. F., Lee, J. E., Seibring, M., Lewis, C., & Keeling, R. P. (2003). Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 484-494. Weitzman, E. R., Nelson, T. F., Lee, H., &

Wechsler, H. (2004). Reducing drinking and related harms in college: Evaluation of the “A Matter of Degree” program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 187-196.