A note from the Editor: The following WAGER was written by Dr. Winters and Dr. Stinchfield, from the University of Minnesota. Following the WAGER are comments by Dr. Rugle, Clinical and Research Director of Trimeridian/Custer Gambling Treatment Program and Dr. Federman, President of GamblingSolutions.

Ken C. Winters, Ph.D.; Randy D. Stinchfield, Ph.D.; Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research

Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

The rapid expansion of legalized gambling has increased concerns that our country is producing a young generation of over-involved gamblers. We now have in this country children who are exposed to high-stakes gambling throughout their social development. However, little is known about the course and outcomes of adolescent gambling behaviors during the period from adolescence through the "transition years" of post-high-school. Because individuals over the age of 17 years have access to lotteries and casinos in some parts of the country, they may face a heightened risk for developing gambling problems.

Since 1990, the Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research at the University of Minnesota has assessed at three points in time (T1, T2 and T3) the gambling behaviors of a sample of young people (N = 305). The T3 assessment was recently completed (1997-1998), at which time the average age of the sample was 23-years-old. The average age at T2 was 18-years-old and at T1, 16-years-old.

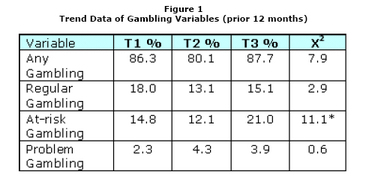

Note: Any Gambling = betting for money in at least one game; Regular Gambling = weekly or more gambling; At-risk Gambling = 2-3 score on SOGS-RA or SOGS; Problem Gambling = 4+ on SOGS-RA or SOGS. The SOGS-RA was administered at T1 and T2 when the subjects were adolescents and the SOGS was administered at T3 when the subjects were adults. Scoring adjustments were made so that both the SOGS-RA and SOGS had a comparable score range of 0-12.

* p<.05

The prospective findings of prior year gambling provide evidence of both stability and change. Stable rates were observed across time with respect to any gambling, regular gambling (defined as weekly or daily gambling) and problem gambling (defined by a score of 4+ on the South Oaks Gambling Screen). On the other hand, the results showed that the rate of at-risk gambling (defined by a score of 2 or 3 on the South Oaks Gambling Screen) significantly increased from the period covering late adolescence to young adulthood (see Figure 1).

Furthermore, several adolescent risk factors were associated with increased gambling abuse during young adulthood. The most prevalent were signs of gambling abuse during adolescence, being male, parental history of gambling, juvenile delinquency, and poor school performance. Many of these variables parallel risk factors identified in research on the development of adolescent substance abuse (e.g., positive family history, being male, juvenile delinquency) (Kandel & Davies, 1992). Thus, it is possible that the underlying roots of these two disorders share important characteristics.

The study supports the view that prevention programs should be implemented prior to the onset of the teenage years, and that teenagers with a high-risk profile should be screened for a potential gambling problem. Particularly in need of such screenings are substance-abusing males who have an early onset of gambling involvement, have a history of juvenile delinquency and school problems, and have at least one family member with a history of gambling problems.

References

Kandel, D.B. & Davies, M. (1992). Progression to regular marijuana involvement: Phenomenology and risk factors for near-daily use. In M. Glantz & R. Pickens (Eds.), Vulnerability to drug abuse (pp. 211-253). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Suggested Readings

Winters, K.C., Stinchfield, R.D., & Kim, L. (1995). Monitoring gambling among Minnesota adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies, 11, 165-183.

Special issue of Journal of Gambling Studies on youth gambling: Fall 2000, Vol. 16, No. 2/3.

Loreen Rugle, Ph.D. Clinical/Research Director Custer Center Gambling Treatment Program/Trimeridian, Inc.

Drs. Winters and Stinchfield present very significant findings and comments in this editorial. A very recent article by Soldz and Cui (2001) also presents similar predictive risk factors for cigarette smoking in adolescents. Clearly there seems to be a population of young people at high risk for a range of addictive behaviors. The risk signs such as lack of academic success, delinquency, substance abuse and parental history of addiction could be easily identified. The challenge is to define and implement appropriate prevention and early intervention strategies and to convince policy makers and funding sources that problem gambling warrants inclusion in often very limited budgets.

It is very important that information be provided to children and adolescents (and their parents) on the potential risks of gambling along with other problem behaviors. However, just providing warnings regarding the consequences of problem gambling may not be sufficient. Research in the area of substance use escalation in adolescents (Wills et al., 1997) suggests that environmental changes such as improved parental marital relationship, tutoring or counseling for the student may enhance "protective" factors that contribute to reduction of problem behaviors.

From a public health perspective, designing integrated interventions which include problem gambling education and also are designed to strengthen the high risk adolescent’s ability to refrain from a wide range of problem behaviors would seem to be a most cost effective approach.

References

Soldz, S. & Cui, X. (2001) A risk factor index predicting adolescent cigarette smoking: A 7-year longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15, 33-41.

Wills, T.A., McNamara,G., Vaccaro, D., and Kirky, A.E. (1997). Escalated substance use: A longitudinal grouping analysis from early to middle adolescence. In G.A. Marlatt & G.R. VandenBos (Eds.), Addictive Behaviors (pp. 97-128). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Edward J. Federman, Ph.D., President, GamblingSolutions

Winters and Stinchfield’s call for gambling prevention programs prior to the teen-age years is supported by a growing body of literature including their own research. Publication of the complete results from their longitudinal study may shed light on protective factors that can inform prevention programming. Additional research remains necessary to determine the most effective broad based prevention programs for children as well as more aggressive prevention efforts for high-risk children. In Connecticut and New Jersey, legislators are working toward mandating early prevention programs. Funding for the necessary research and programming, in most cases should come from the states. This is a modest proposal when one considers that the unrealized promises to devote lottery revenues to education convinced many that initiating a lottery in their state was, in balance, worthwhile.

The WAGER is a public education project of the Division on Addictions at Harvard Medical

School. It is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible Gaming, Behavioral

Health Online, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Addiction Technology

Transfer Center of New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.