While outcome research for disordered gambling is limited (e.g., Sylvain, Ladouceur, & Boisvert, 1997), a review of gambling treatment studies (Kassinove, 1996) suggests that treatment can have a positive effect on disordered gamblers. Research conducted by Hodgins, Currie, & el-Guebaly (2001) comparing two self-help treatment approaches posits similar results.

After recruiting a sample population (N=102) that met criteria for disordered gambling according to the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesuier & Blume, 1987) and then obtaining a brief gambling history, Hodgins et al. (2001) divided the sample into three groups: Group 1 (n=35) was mailed a self-help workbook[1] (Hodgins & Makarchuk, 1998); Group 2 (n=32) was mailed the same self-help workbook as Group 1 after receiving a motivational telephone interview (Miller & Rollnick, 1991); and Group 3 (n=35), the waiting list control group, received neither the self-help workbook nor the motivational telephone interview. One-, three-, six-, and twelve-month follow-up assessments were conducted.

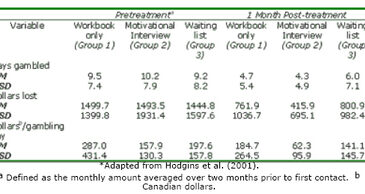

According to Hodgins et al. (2001), preliminary analyses of gambling involvement (i.e., days gambled per month, total amount of dollars lost per month, and average amount of dollars lost per day) revealed a significant time effect. Specifically, after one month, Groups 1, 2, and 3 reported considerably less gambling involvement than they reported at pretreatment. Table 1 presents these results.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of gambling involvement for Groups 1, 2, and 3 at the 1-month follow-up assessment*

One-month follow-up assessment data confirmed that Group 2 showed significantly more improvement after one month of treatment than Group 3 (Hodgins et al., 2001). The former group gambled fewer days, lost less money, and spent less money per gambling day than the latter. No statistically significant differences were found between Groups 1 and 3.

At the three-month follow-up, Hodgins et al. (2001) found significant differences between Groups 1 and 2: Group 2 gambled fewer days, lost less money, and spent less money per gambling day than Group 1. However, no significant differences were found between Groups 1 and 2 at the six- or twelve-month follow-up assessment periods. Overall, 21.4% of Group 1 participants were abstinent at the 12-month follow-up assessment, compared to 29.6% of Group 2 participants. Moreover, the extent of gambling disorders (57.1%) among Group 1 participants diminished at the 12-month follow-up compared to the prevalence of gambling disorders (59.3%) among Group 2 participants. While data collected by Hodgins et al. (2001) show that the short-term effects of the self-help treatments are sustained over a 1-month time period, no significant effects occurred at the 1-year follow-up.

Some very important treatment issues were not considered in this paper. For example, what would be the effect if the waiting list control group had waited longer than four weeks? Does the treatment itself have any adverse consequences? Do some people get worse? One-year follow-up periods are simply insufficient. George Vaillant reminds us that we should consider treatment outcomes for addictive behaviors as we do cancer treatments. Efficacy determinations should be made intermittently for about five years post-treatment before meaningful outcome can be determined. This kind of treatment outcome research will cost money. However, without this data, we might be mislead into thinking that 1-month post-treatment effects will endure. Hodgins et al. (2001) have shown that their brief interventions only have short-term efficacy.

Hodgins et al. (2001) have contributed to what is arguably a rather limited body of research on treatment outcomes for disordered gambling. Their work also has fallen victim to some common perils of treatment outcome research. Because short-term treatment benefits often erode over time, treatment for gambling and other addictive behavior patterns should be conceptualized as long-term events that can be divided into brief episodes. Consequently, like Hodgins et al. (2001), we encourage the use of “booster” interventions to extend short-term treatment effects.

[1] The workbook is split into self-assessment, goal setting, strategy, maintenance and other resource sections.

References

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., & el-Guebaly, N. (2001). Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 50-57.

Hodgins, D. C., & Makarchuk, K. (1998). Becoming a winner: defeating problem gambling. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press.

Kassinove, J. I. (1996). Pathological gambling: the neglected epidemic. The Behavior Therapist, 19, 102-104.

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184-1188.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press.

Sylvain, C., Ladouceur, R., & Boisvert, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: a controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 727-732.

The WAGER is a public education project of the Division on Addictions at Harvard Medical

School. It is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible Gaming, the

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Addiction Technology Transfer Center of

New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.