The action at the Olympic Games in Australia has heated up and, presumably, so has the gambling action as well. Gaming among indigenous cultures is no exception, and may be increasing among the indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

While the economic benefits of gambling in general remain undetermined, the benefits to impoverished areas within the United States have been recognized (National Research Council, 1999). A good example of how gambling can advance an economy is Foxwoods Casino in Mashantucket, Connecticut. The economic benefits of gambling for the poorer areas of the United States might also apply to the impoverished areas of New Zealand and Australia.

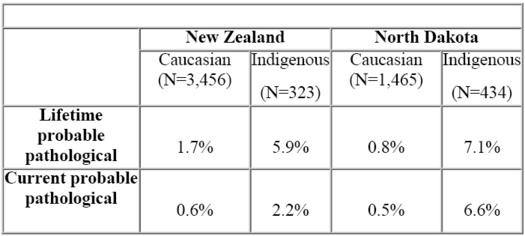

Research shows that indigenous peoples in New Zealand and the United States (i.e., North Dakota), like their Caucasian counterparts, participate in a variety of gambling activities including lotto, bingo, card games for money, raffle games, and horse racing (Volberg & Abbott, 1997). What’s striking is that indigenous peoples in these parts of the world are more likely to gamble on a regular basis than their Caucasian counterparts. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that indigenous peoples in both countries spend more money on gambling activities and have higher current and lifetime prevalence rates for pathological gambling (Volberg & Abbott, 1997).

The strength and nature of this relationship deserves more attention. The Caucasian samples are considerably larger than the Indigenous samples; this circumstance might provide less stable prevalence estimates from the smaller samples. While the prevalence rates between the Indigenous and Caucasian samples are indeed different within a culture, cross-cultural comparisons are problematic.

Cross-cultural research is complex and often difficult to interpret. For example, responses to surveys may reflect different meanings across cultures, especially when considering the possibility that one indigenous culture might value gambling very differently than another indigenous culture from a different part of the world. Moreover, the data from these different groups is not quite comparable since different sampling strategies were employed when measuring the indigenous peoples of the United States (i.e., North Dakota) and New Zealand.

Nevertheless, this research is valuable: it identifies high-risk groups for pathological gambling, and opens the door to future examinations of problem gambling within indigenous cultures. As a recent WAGER reported, the rates of gambling problems within the general population are quite consistent across a variety of studies. Therefore, the future of prevalence research, in the United States and around the world, may be most fruitful if it begins to focus more attention on high-risk groups.

References

National Research Council. (1999). Pathological gambling: a critical review. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

Volberg, R.A. & Abbott, M.W. (1997). Gambling and problem gambling among indigenous peoples. Substance Use and Misuse, 32, 1525-1538.