When the Iowa farmer in the Hollywood movie, "Field of Dreams," inspired by a voice from the sky that said, "If you build it, he will come," built a baseball diamond in the middle of his cornfield, Shoeless Joe Jackson and others came to play ball. The investors in the casino boat Midnight Gambler had no such luck. They had leased the 108-foot casino boat with high hopes that it would sail from Provincetown, Massachusetts every day, filled with eager gamblers. Even though the priest at the town’s annual Blessing of the Fleet sanctified the Midnight Gambler, it went belly-up in August after only two months in operation. Each time the boat sailed out one hour into international waters to escape the state’s casino gambling prohibition, it carried fewer than fifty gamblers, barely one-fifth of its capacity. No one had expected it to fail, especially not the local selectmen and residents who had feared that the boat would bring hordes of gamblers and attendant problems of crowding, parking, and crime.

What went wrong? Many things. The days were chilly and rainy; the seas were rough. For a $29 cover charge patrons got a buffet, a piano player, and an open upper deck in addition to gambling. They had to buy their own Dramamine at the bar for $1 a pill. Gamblers had to wait almost an hour before the boat reached international waters to begin gambling, and they had to stop gambling an hour before the boat docked. Losers had no chance to "chase" their losses.

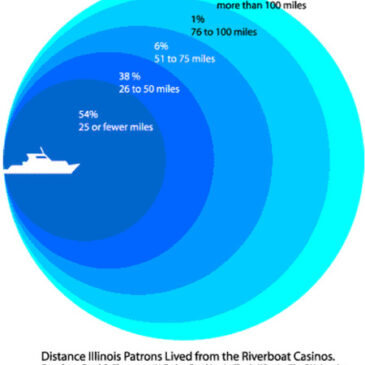

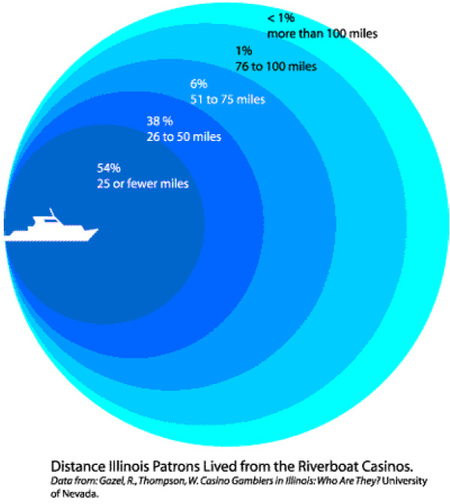

Since these reasons might be sufficient to discourage people from gambling on the Midnight Gambler, perhaps a more compelling question is, who were the people that gambled on the boat despite the discomforts? The authors of "Casino Gamblers in Illinois: Who are They?" identified patrons on the state’s commercially successful riverboats. By generalizing their results to Massachusetts, we can shed light on the Provincetown experience. Gazel and Thompson conducted a demographic study of 785 patrons of five of Illinois’ riverboat casino sites. The figure below summarizes the distance patrons lived from the riverboat site at which they gambled.

Contrary to conventional expectations that suggest gambling is a lure, Gazel and Thompson found that most of the Illinois riverboat gamblers were not tourists; they were local residents. If, like the Illinois riverboat gamblers, the main purpose for visiting Provincetown for the majority of the patrons of the Midnight Gambler was to gamble, then they did not come from the established tourist population, which comes to Provincetown to enjoy the artist colony and gay resort.

The owners of the Midnight Gambler assumed that they would have the financial success of riverboats like those in Illinois, perhaps because they believed that gambling was a sufficient lure. Perhaps they did not forecast the poor market for casino boat gambling nor the bad weather on Cape Cod. Gambling ventures, like most other investments, are not guaranteed to succeed. When gambling ventures fail, it encourages us to rethink the notion that gambling is a "lure" that can attract patrons regardless of the social setting. In addition, it encourages gaming entrepreneurs to consider carefully the potential market for gambling as well as how their new gambling venture might influence local residents-according to the findings of Gazel and Thompson, these people might comprise more of the projected market than expected.

References

Gazel, R. C., & Thompson, W. N. (1996). Casino Gamblers in Illinois: Who Are

They?, [http://www.bettergov.org/gambling.htm website]. The Better

Government Association.