Contrary to popular perception, the state regulation of gambling is not an exclusive product of Enlightenment-era classic liberalism. Some seven centuries before the first neon sign lit the Las Vegas Strip, Spanish dice throwers became subject to a set of royal mandates that severely curtailed their activities. The latter half of the thirteenth century bore witness to the sweeping reforms in laws concerning gambling, a change primarily promulgated by Alfonso el Sabio (1252-1284; (1). Redacted into a single treatise, the Ordenamiento de las tafurerias, the scope and purpose of Alfonso’s legislation are not entirely dissimilar from those of contemporary gambling jurisprudence. Only royally sanctioned gaming houses were permitted; private enterprises were explicitly prohibited. The tools of the gambling trade were likewise tightly controlled, and the use of weighted or altered dice was punished severely. An arbitration procedure was instituted to adjudicate gambling table disputes, and physical violence resulted in a myriad of judicial penalties. Damaging the gaming tables was fined at the rate of one maravedi per blow dealt. This punitive paradigm was suspended, however, when the perpetrator’s head was the implement of destruction. While the head-inflicted damage was still illegal, punishment was waived as it was thought that the perpetrator had probably suffered enough. Thirteenth century Spain was a multicutural land, with Muslims, Jews, and Christians living together. While non-Christian Spaniards were welcomed in the gaming houses, they enjoyed an inferior legal status and were subject to different penalties than their counterparts.

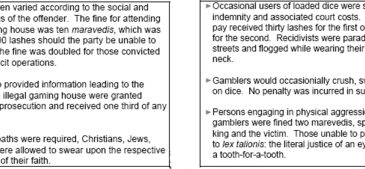

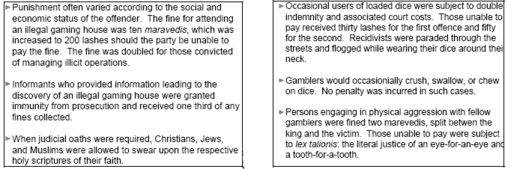

The particulars and peculiarities of medieval jurisprudence are intriguing and novel, but their study can also illuminate the present legal discourse on gambling. Alfonso’s legislation was hardly aimed at eliminating gambling from his Spain. Rather, the Ordenamiento de las tafurerias has two primary concerns. The first ensures that all gaming acivities be under the jurisdiction of the Crown, and that the latter receive a portion of any revenues generated. Secondly, gambling was regulated with the intent of preventing disturbances in the social order. Gambling may have been acceptable, but the sometimes-associated offenses of violence, fraud, and blasphemy were not. When the Draconian penalties (see below) are extracted and the laws are examined through the contextual lens of history, the gaps that separate them from our own seem to narrow considerably. Below is a selection of points from the Ordenamiento.

Source: Carpenter, D.E. (1988). Fickle fortune: Gambling in medieval Spain. Studies in Philology, 85(3), 267-278.

This public education project is funded, in part, by The Andrews Foundation and the National Center for Responsible Gaming.

This fax may be copied without permission. Please cite The WAGER as the source.

For more information contact the Massachusetts Council on Compulsive Gambling,

190 High Street, Suite 6, Boston, MA 02110, U.S.