The scratch cards now offered by many state lotteries have become as ubiquitous in convenience stores as cold coffee and day-old doughnuts. Colorful game cards, usually costing a few dollars or less, can now be purchased in vending machines in public areas (e.g., in one Massachusetts convenience store, 30 different varieties of cards were available). Similar to the mechanisms of promotional game cards distributed by fast-food restaurants and mail-order firms, the scratch-off cards sold by state lotteries often involve the removal of a silver coating to reveal instantly a win or a loss. As with other lottery games, minors are prohibited from playing. Given the high visibility, low cost, and familiar mechanism of scratch cards, are children and adolescents particularly prone to this form of gambling? Wood and Griffiths (1998) set out to study the nature of scratch card participation among adolescents in the United Kingdom, where this form of gambling has been legal for adults since March of 1995. In their first year of availability, the National Lottery “Instants” generated 1.1 billion pounds, roughly a quarter of total lottery revenue for that year. The authors used a sample consisting of 1,195 adolescents aged 11to 15-years-old (46.0% male, 53.6% female, 0.3% unspecified, mean age=13.3 years). Respondents were students who completed a 55 question instrument that included items based on the DSM-IV-J diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling.

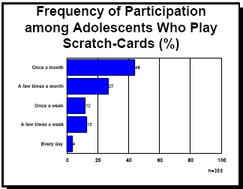

Of the 30% of the total sample that had ever played scratch-cards, 6% met DSM-IV-J criteria for pathological gambling, a figure nearly identical to that obtained for adolescents who had ever played the regular, non-instant National Lottery. Yet the most interesting numbers presented in this study may not involve frequency of play. In the United Kingdom, lottery gambling by persons under 16 years old (e.g., the entire sample) is prohibited. Of course, it is naive to think that any government mandate can have the power to totally block participation by minors. Thus, adolescents wishing to obtain scratch-cards must procure them either illicitly or through a third party. This study proposes that, in many instances, third party may be the minor’s own parents. Of scratch-card playing adolescents, 57% reported that their scratch cards had been purchased for them by their parents. For general National Lottery tickets, the figure rose to 71%. Furthermore, the authors noted a significant correlation between child and parental lottery gambling (scratch-cards: r=0.37838, p<0.0005; general National Lottery: r=0.26567, p<0.0005). It should be remembered that these figures were obtained from self-reports of the adolescent respondents and not their parents. These findings suggest that repetition of an observed action is not the only means through which gambling behavior is transmitted. Rather, parents actively include and socialize their children to gambling by providing them with gambling materials. It should be noted, however, that the National Lottery and its scratch cards are less than 5 years old, and it is possible that these participation figures represent an initial rush to try out a novel activity. Nevertheless, popular media often portray adolescent participation in illicit activities as fomenting covertly behind the backs of parents totally ignorant of their child’s behavior. The present study contradicts this paradigm, and may suggest the need to reevaluate the role of parents in the development of adolescent gambling behavior.

Source: Wood, T.A., & Griffiths, M.D. (1998). The acquisition, development and maintenance of lottery and scratchcard gambling in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 265-273.

This public education project is funded, in part, by The Andrews Foundation and the National Center for Responsible Gaming.

This fax may be copied without permission. Please cite The WAGER as the source.

For more information contact the Massachusetts Council on Compulsive Gambling, 190 High Street, Suite 6, Boston, MA 02110, U.S. {