Substance use is part of the scientific sphere and a persistent influence on the arts and humanities. The topic of substance use in the arts tends to come in waves; currently, it plays a significant role in the media, for example, because of numerous reports of actor and musician arrests for use and possession of various illicit substances. However, substance use imagery (SUI) as a part of the arts, specifically music, is not a new phenomenon; it also is not limited to US culture. To demonstrate the ever present nature of substance use in music, in this issue of Addiction & the Humanities we briefly deconstruct one example of substance use in music. We look at Myriam Munne’s exploration of drinking and alcohol imagery in tango lyrics from 1914 to 1977.

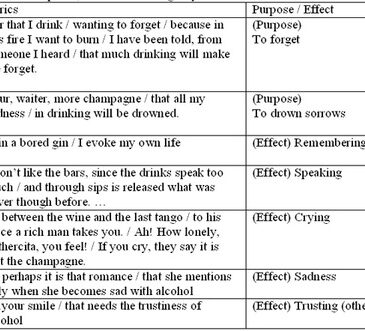

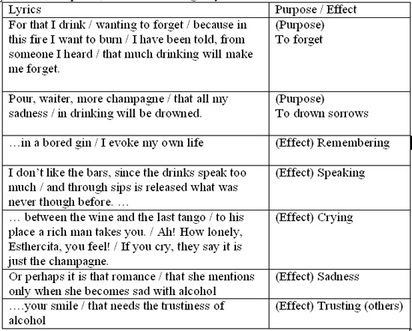

Munné analyzed 82 Argentinean tangos by focusing on the prevalence of drinking and drunkenness in their titles and lyrics. She explored the system of beliefs, myths, and attitudes related to alcohol through the tango. Munné described the tango as a phenomenon of mass culture and suggests that alcohol consumption is a social act1. She concluded that most tangos are about subjects with universal permanence: alcohol’s role in the tango is usually tied to love, and the use of alcohol in tango lyrics highlights its priority. Munné listed the pretexts for drinking: betrayal, rejected love, and sad themes; the different purposes for drinking: to forget and to drown sorrows; and the various effects: remembering, speaking, crying, being sad, and trusting others (Munne, 2003).

Table 1: Purposes & Effects in Tango Lyrics.

The increased amount of SUI imagery in the tango reveals the role of alcohol and drinking in Argentinean culture. In fact, in recent years the country was becoming increasingly aware of alcohol related problems (Munne, 2003). Munné writes that the tango “[served] as a medium for the expression of the feelings, desires, and frustrations of the population (pg. 417).” This compares well to the role of music in American society and its representation of changing ideas about substance use and consequences. Differences in popular opinion, society, artists lives (the experiences that they pull from), and traditions within cultures lead to a range, from positive to negative and from inflammatory to conciliatory, in SUI. Here in the United States, SUI in music enters the popular news sphere in waves. For example, in a 1999 study of SUI in popular movies and music, the Office of National Drug Control Policy found that of 1000 songs, a little more than 25% had direct references to various substances. This finding is reinforced by other studies from the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine (Primack, Dalton, Carroll, Agarwal, & Fine, 2008) and from discussions held at the November 2007 American Public Health Association Meeting (Content Analysis of references to substance abuse in popular music, 2007). Although these negative images stand out, in 2005, singer Kelly Clarkson’s SUI-free “Since You’ve Been Gone” was a top hit on music charts, proving that music with less SUI also can be popular.

Based on the above example, and report references, the presence of substance use images in the arts is not limited to specific genres, time periods, or cultures. The role of SUI in music is best described as two-fold: artists see it positively because it allows for free commentary on society; alternatively, those who focus on the influence that SUI has on listeners view it negatively. Artists use SUI as a positive outlet and a constructive way to comment on changes in society as these relate to substance use and addiction. As the popular music of the time and culture, the tango allowed the Argentinean population to look at themselves critically, and contemporary popular music should allow us to do the same. Researchers, educators, and parents often question how to curb the influence of references to substance use. It is evident that the prevalence of SUI in music reflects the society listening to that music. In reality, limiting the influence of SUI is as constant as SUI’s prevalence. Prevention programs, messages intended to limit substance use, and other forms of pre-emptive anti-substance abuse pressure have to be as strong and as persistent as SUI’s initial influences on listeners to succeed at demonstrating the possible negative consequences of substance use.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Ingrid R. Maurice.

Notes

1 Munne uses "An anthropological view of alcohol and culture in

international perspective"(1995) by Heath as a reference for this

definition.

References

Content Analysis of references to substance abuse in popular music. (2007). Paper presented at the American Public Health Association 135th Annual Meeting and Expo, Washington, D.C.

Munne, M. I. (2003). Drinking in tango lyrics: an approach to myths and meanings of drinking in Argentinian culture. Contemporary Drug Problems, 23(8), 415-439.

Primack, B. A., Dalton, M. A., Carroll, M. V., Agarwal, A. A., & Fine, M., J. (2008). Content Analysis of Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs in Popular Music. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine, 162(2), 169-175.