Many substance use studies focus either on specific subpopulations or specific programs for reducing harms. To examine trends in the greater population, including trends that indicate increasing or decreasing prevalence of substance use disorders, researchers conduct large, population-wide studies. This week, The DRAM reviews a comparison of findings from two waves of a seminal study of alcohol use in the US by Bridget F. Grant and her colleagues.

What was the research question?

How have the prevalence rates for past-year alcohol consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol use disorder changed from 2001-2002 to 2012-2013?

What did the researchers do?

Grant and her colleagues used data from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) and the 2012-2013 NESARC-III. Both studies surveyed the US general population using random sampling and face-to-face interviews. In both surveys, participants provided demographic information and responded to items about any past-year alcohol use and episodes of high-risk drinking,[1] as well as an assessment of past-year alcohol use disorder. The researchers used participants’ responses to estimate the population-wide prevalence rates for alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and alcohol use disorder in 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. They used t-tests to determine whether any changes from 2001-2002 to 2012-2013 were statistically significant.

What did they find?

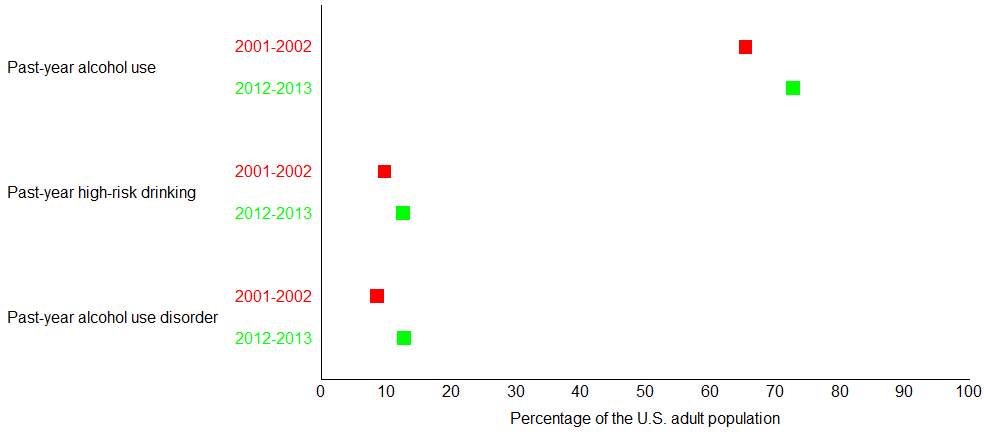

The prevalence rate for past-year alcohol use increased significantly from 65.4% in 2001-2002 to 72.7% in 2012-2013. Past-year high-risk drinking and past-year alcohol use disorder also increased significantly-over the same ten-year period (see Figure). The prevalence rates for women increased dramatically (high-risk drinking: from 5.7% to 9.0%, alcohol use disorder: from 4.9% to 9.0%).

Figure. Prevalence rates for past-year alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and past-year alcohol use disorder. Adapted from Grant et al., (2017). Click image to enlarge.

Figure. Prevalence rates for past-year alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and past-year alcohol use disorder. Adapted from Grant et al., (2017). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

In the same way that the U.S. Census is used to track changes in population and demographics, the NESARC tracks national trends in alcohol use, drug use, and a selection of mental health issues. Using data from the NESARC, research can examine trends in alcohol use over the population as a whole and within some demographic groups. The next step will be to explore whether the reasons for these increases are temporary (e.g., stress caused by the recession and economic upheaval in 2008) or part of a trend that could continue further into the future. Once researchers and clinicians understand the reasons for these increases in alcohol use, they can recommend additional prevention and treatment programs – both universal campaigns designed to appeal to the general population and targeted efforts tailored to specific at-risk groups.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

The NESARC’s sampling frame did not include people experiencing homelessness or incarceration, two groups that might have higher than average rates of alcohol use disorder. The response rates for the NESARC and NESARC-III were also significantly different (80.1% and 60.1%, respectively). Some contend that this difference in response rate can be traced to differences in the two surveys’ methodologies, and that the results of the two surveys may not be directly comparable. Additionally, the two surveys collected data from different people, so we do not know how individuals’ alcohol consumption changed over time.

For more information:

For more on the NESARC survey itself, click here. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is the institute within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that supports and conducts research on the impact of alcohol use.

— Matthew Tom

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] High-risk drinking for men was defined as drinking five or more “standard” drinks in a single day. High risk-drinking for women was defined as drinking four or more “standard” drinks in a single day.