Gambling fallacies (i.e., mistaken beliefs about how gambling works, such as the belief that certain items may be “lucky”) predict and maintain gambling-related problems. Several treatment and prevention measures for gambling-related problems therefore focus on correcting gambling fallacies. However, most studies supporting the link between gambling fallacies and gambling-related problems have been cross-sectional, making it impossible to determine whether the gambling fallacies precede the gambling-related problems. Meanwhile, other research has identified additional factors that are strong predictors of gambling-related problems, including aspects of gambling involvement such as gambling frequency and number of games played.

In a 2016 paper, Carrie Leonard and Robert Williams attempted to clarify the relationship between gambling fallacies, related factors, and gambling-related problems using a longitudinal study design and a new measure of gambling fallacies. This week, the WAGER reviews their work.

What was the research question?

What is the relationship between gambling fallacies and gambling-related problems?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used data from the Quinte Longitudinal Study that studied gambling in the general population of Ontario, Canada. From a sample of Ontarians (n = 4,121) that matched the age and gender distribution of the greater population of Canada, individuals with gambling involvement were recruited for the present study, with a 21.3% response rate (n = 1,056). Of these 1,056 individuals, 93.9% completed the five-year study.

Participants completed a self-administered computerized questionnaire each year for five years that included the Gambling Fallacies Measure (GFM)1 to measure their gambling-related cognitive errors, and the Problem and Pathological Gambling Measure (PPGM) to classify them as either non-gamblers, recreational gamblers, at-risk gamblers, problem gamblers, or pathological gamblers. Additionally, the questionnaire collected information about gambling involvement and behavior, demographics, and a number of other variables.

The researchers conducted a generalized estimating equation — a statistical test to determine if GFM scores at each year could predict PPGM gambling category during the next year. They also looked at what other factors could predict the year’s PPGM category.

What did they find?

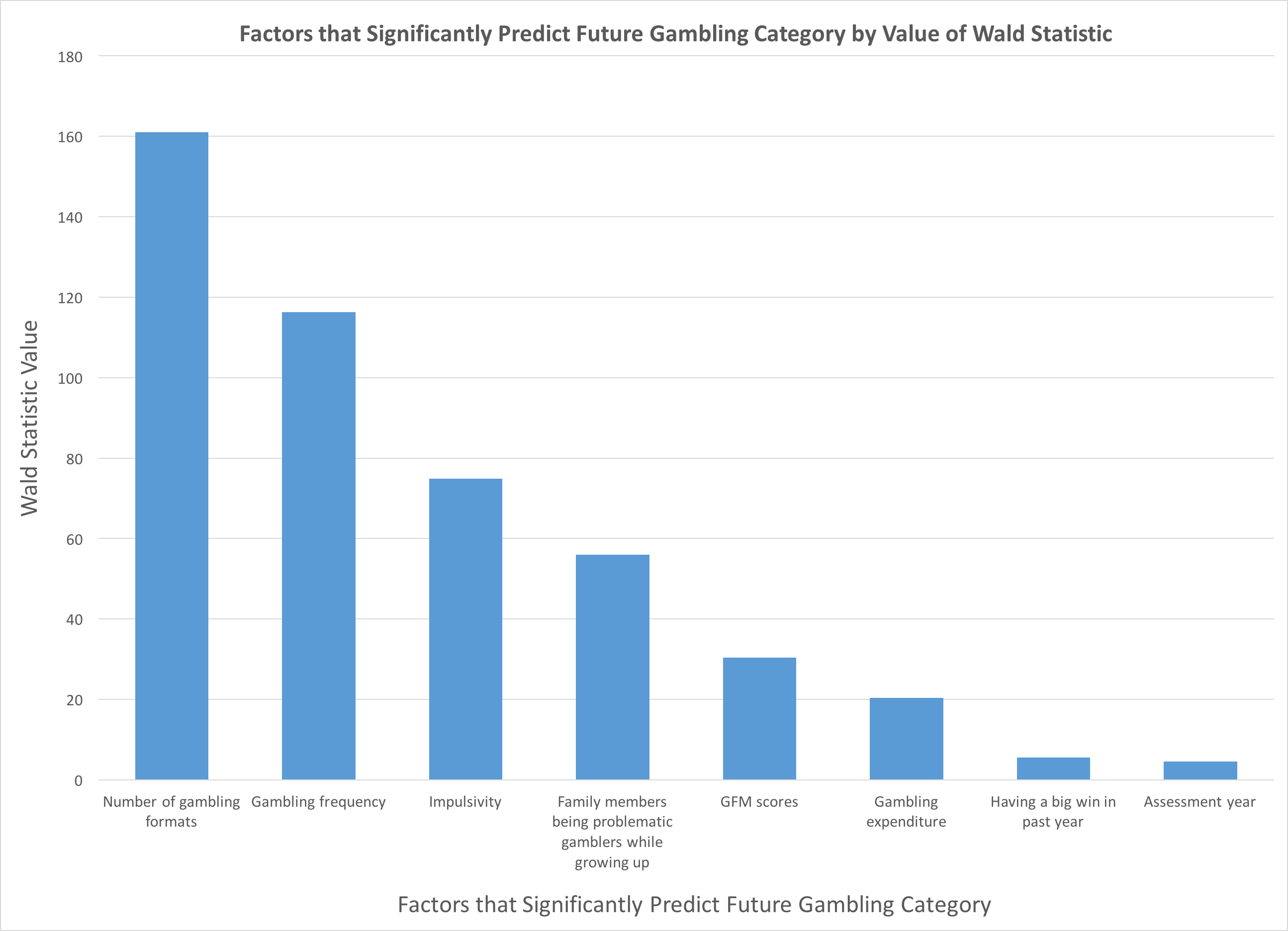

GFM scores did predict the next year’s PPGM gambling category. This means that individuals with more gambling fallacies were more likely to be categorized as problem or pathological gamblers later on. However, several other variables were found to have a much stronger relationship with future PPGM category. Among these are two variables that make up gambling involvement: number of gambling formats engaged in, and gambling frequency.

Figure. Factors that predict future PPGM gambling category by Wald statistic. A high Wald value indicates that the factor is a strong predictor of future PPGM gambling category. All Wald statistics represented here are statistically significant. Adapted from Leonard & Williams (2016). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings indicate that gambling fallacies precede gambling problems, but the relationship is complex. Additionally, the finding that measures of gambling involvement were strong predictors of future gambling category adds further evidence to the “involvement effect” demonstrated in previous research. Going forward, developing a more nuanced model of what factors precede and maintain gambling problems has implications at both a clinical and a programmatic level, as clinicians will better be able to screen individuals for gambling problems based on empirically supported risk factors, and institutions can design improved interventions to prevent and treat gambling-related problems.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The GFM and PPGM are newly developed measures that have not been used widely, meaning that further research may be needed to validate these measures. The use of these two measures may somewhat limit the ability to compare results of this study to those of previous studies that have use different measures.

For more information:

Our addiction resources page contains free screening and self-help tools if you or a loved one are concerned about gambling-related problems.

— Rhiannon Chou Wiley

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1 Example items are as follows:

How lucky are you? If 10 people’s names were put into a hat and one name drawn for a prize, how likely is it

that your name would be chosen? (correct answer = About the same likelihood as everyone else)

If you were to buy a lottery ticket, which would be the best place to buy it from? (correct answer = one place is as good as another)

You have flipped a coin and correctly guessed ‘heads’ 5 times in a row. What are the odds that heads will come up

on the next flip. Would you say… (correct answer = 50%).

Marsha August 16, 2017

After reading this, I am not sure the “fallacies” that the gambler holds are really pointed out or clear herein?

Heather Gray August 16, 2017

Thanks for your comment, Marsha. We open the post by referring to gambling fallacies as “mistaken beliefs about how gambling works, such as the belief that certain items may be ‘lucky.'” You can learn more about the specific measure the authors used (the Gambling Fallacies Measure) by reading the paper we link to in the What did the researchers do? section.

Some example questions are as follows:

How lucky are you? If 10 people’s names were put into a hat and one name drawn for a prize, how likely is it

that your name would be chosen? (correct answer = About the same likelihood as everyone else)

If you were to buy a lottery ticket, which would be the best place to buy it from? (correct answer = one place is as good as another)

You have flipped a coin and correctly guessed ‘heads’ 5 times in a row. What are the odds that heads will come up

on the next flip. Would you say… (correct answer = 50%).

We will add these examples to the post.