Today’s review is part of our month-long special series, Open Science Practices in Addiction Research. During this special series, The BASIS features recent publications that have used contemporary open science practices.

Despite large-scale public health campaigns, diseases related to alcohol are still leading causes of death in the US. One approach to harm reduction that has not yet been implemented here are graphic pictorial health warnings on alcohol containers, similar to those used on cigarette packs in the EU. Although these types of warnings are perceived to be effective, they also can elicit defensive coping mechanisms, such as avoiding looking at the warnings themselves. Enhancing a person’s positive self-concept by affirming their self-worth might reduce defensive responses. This week, The DRAM reviews a pre-registered study by Carlos Sillero-Rejon and colleagues available online through open access that examined how self-affirmation and exposure to different types of graphic pictorial health warnings1 on alcohol containers influence beliefs about drinking.

What were the research questions?

Does self-affirmation change how people view moderate and severe health warning images on beer cans?

What did the researchers do?

Sillero-Rejon and his colleagues recruited 128 regular alcohol drinkers. They randomly assigned the participants to either a self-affirmation group or a control group. In the self-affirmation group, participants wrote an essay about their most important value. Next, both groups viewed images of six moderately-severe and six highly-severe health warning labels on beer cans. Then, the participants completed a survey that assessed their (1) avoidance, or how much they would like to avoid thinking about the warning label, (2) reactance, or how negatively they viewed the warning label, (3) susceptibility, or how likely they think they are to experience the negative consequences shown in the warning label, (4) perceived effectiveness of the warning label, and (5) motivation to drink less alcohol. Following open science practices, the authors pre-registered their detailed research plan with the Open Science Framework before conducting the study, made their article available for free to the public via open access, and provided public access to their dataset online in the University of Bristol Research Data Repository.

What did they find?

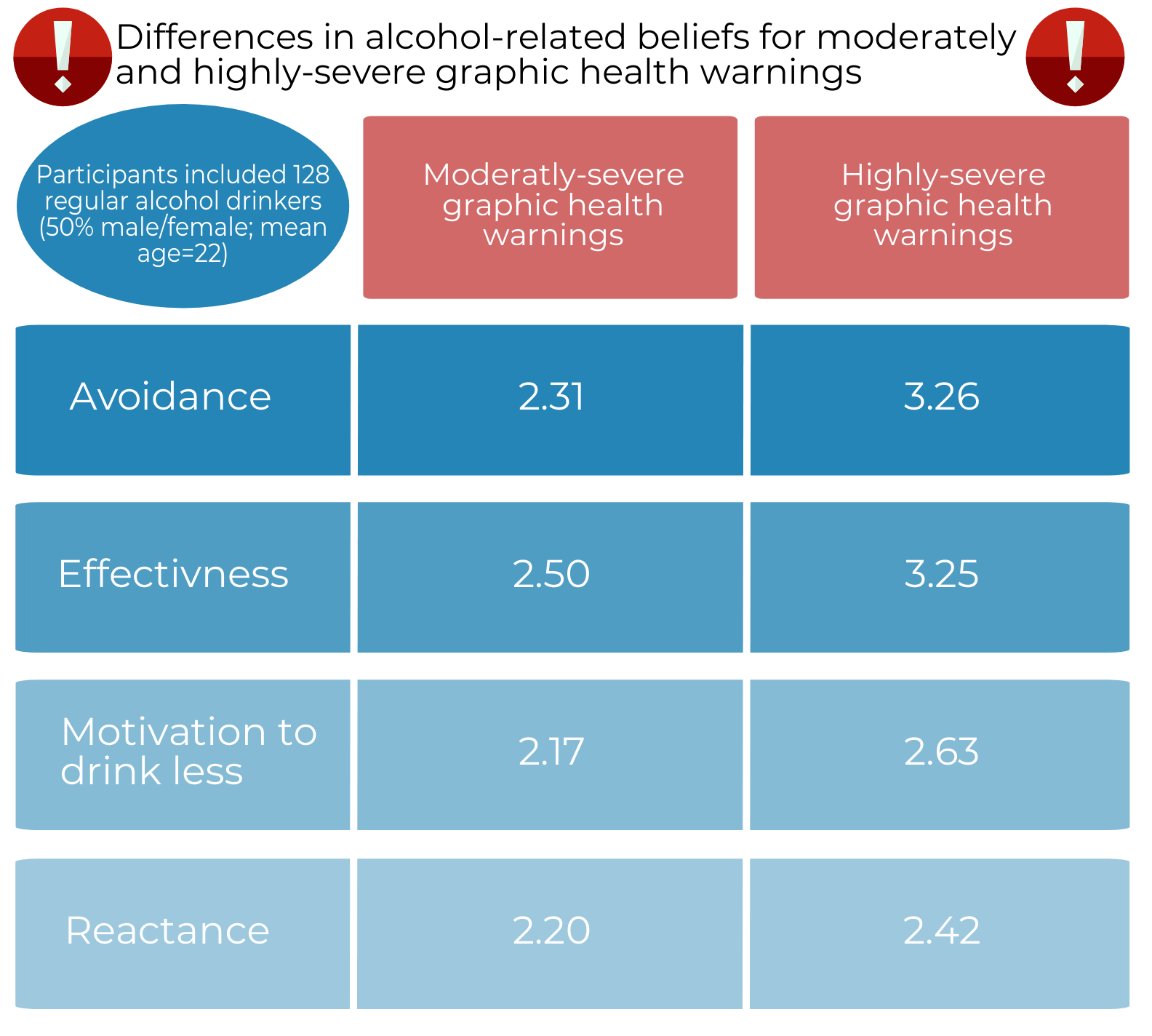

The highly-severe health warnings were perceived to be more effective than moderately-severe labels and appeared to increase motivation to reduce drinking. However, they also produced significantly higher avoidance and reactance scores (see Figure). Contrary to expectations, there was no effect of self-affirmation on any of the outcomes.

Figure. Figure shows statistically significant differences in self-reported beliefs for moderately-severe graphic pictorial health warnings and highly-severe graphic pictorial health warnings in the full sample. Darker blue bars indicate larger differences between means. The mean difference for self-reported susceptibility was not statistically significant and is not shown in the figure. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The results are important for developing public health interventions for health warnings on alcohol packaging. Researchers should consider testing multiple types of alcohol health warnings across different sociocultural contexts with larger, representative samples, as has been done with cigarettes in a study of current smokers from 27 European nations. Moreover, the defensive reactions elicited by the graphic images of health problems and non-significant effects of self-affirmation suggests that other types of health campaigns might be more effective in reducing problem drinking. For example, a social media and online video campaign that educated participants about responsible drinking behaviors was shown to increase the use of techniques to reduce alcohol-related harm and to instill confidence in controlling participants’ drinking.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study was based on an online survey in the United Kingdom using a convenience sample of regular drinkers, so its findings may not generalize to other locations or populations of alcohol users such as binge drinkers. Though the essay task has enhanced self-affirmation in other studies, it might not have done so in this study. Using self-reported data may also reduce the validity of the findings, because participants might not accurately report their drinking beliefs and behaviors.

For more information:

The National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page. For more information about Open Science practices, check out the OSF website.

— Eric R. Louderback, Ph.D.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

1. The graphic-based pictorial health labels illustrated (1) liver cirrhosis, (2) brain damage, (3) mental illness, (4) cancer, (5) road accidents and (6) risk to an unborn child, all of which are potential consequences of heavy drinking.