Negative health consequences associated with substance use can begin at a young age and persist throughout a person’s life. In fact, one of the most common adverse childhood experiences (ACE) is living with a parent or caregiver who has a problem with drugs or alcohol. Being exposed to this type of trauma can lead to lifelong physical and psychological harm. However, historically, substance use treatment has focused on the experiences of adults and neglects the experiences of children who may have been exposed. Pediatric hospitals are positioned to expand community-based substance use education, treatment, and prevention efforts. This week, STASH reviews a study by Rose Hardy and colleagues that examined the extent to which children’s hospitals across the United States implement substance use prevention strategies within their communities and identified these specific strategies.

What were the research questions?

(1) To what extent do children’s hospitals implement substance use strategies within their communities? (2) What are some of the specific strategies that have been adopted?

What did the researchers do?

The authors gathered data from the community health needs assessments (CHNA) of 233 United States children’s hospitals conducted between the years of 2015-2019, including their community benefit activity implementation strategies. After accounting for missing CHNA data, the sample consisted of 206 hospitals. The researchers coded the remaining CHNAs (yes/no) to determine (1) whether the CHNA was completed in collaboration with another hospital or public health department (2) whether communities identified a substance use disorder (SUD) need, (3) if implementation strategies (e.g., treatment, prevention, education) were used in communities with identified SUD needs, and (4) if their SUD strategy targeted pediatric populations.

To examine which hospitals were more likely to offer substance use services, the authors identified characteristics of the hospital’s surrounding community (e.g., overdose rate, income inequality) and compared that to the characteristics of the hospitals in that community (e.g., the number of beds, whether they collaborated in completing their CHNA). They used t-tests and chi-square exact tests to assess for differences in hospitals that did/did not provide SUD services and conducted a binary logistic regression to assess whether the community’s expressed need was indicative of the hospital’s services regardless of community/hospital characteristics.

What did they find?

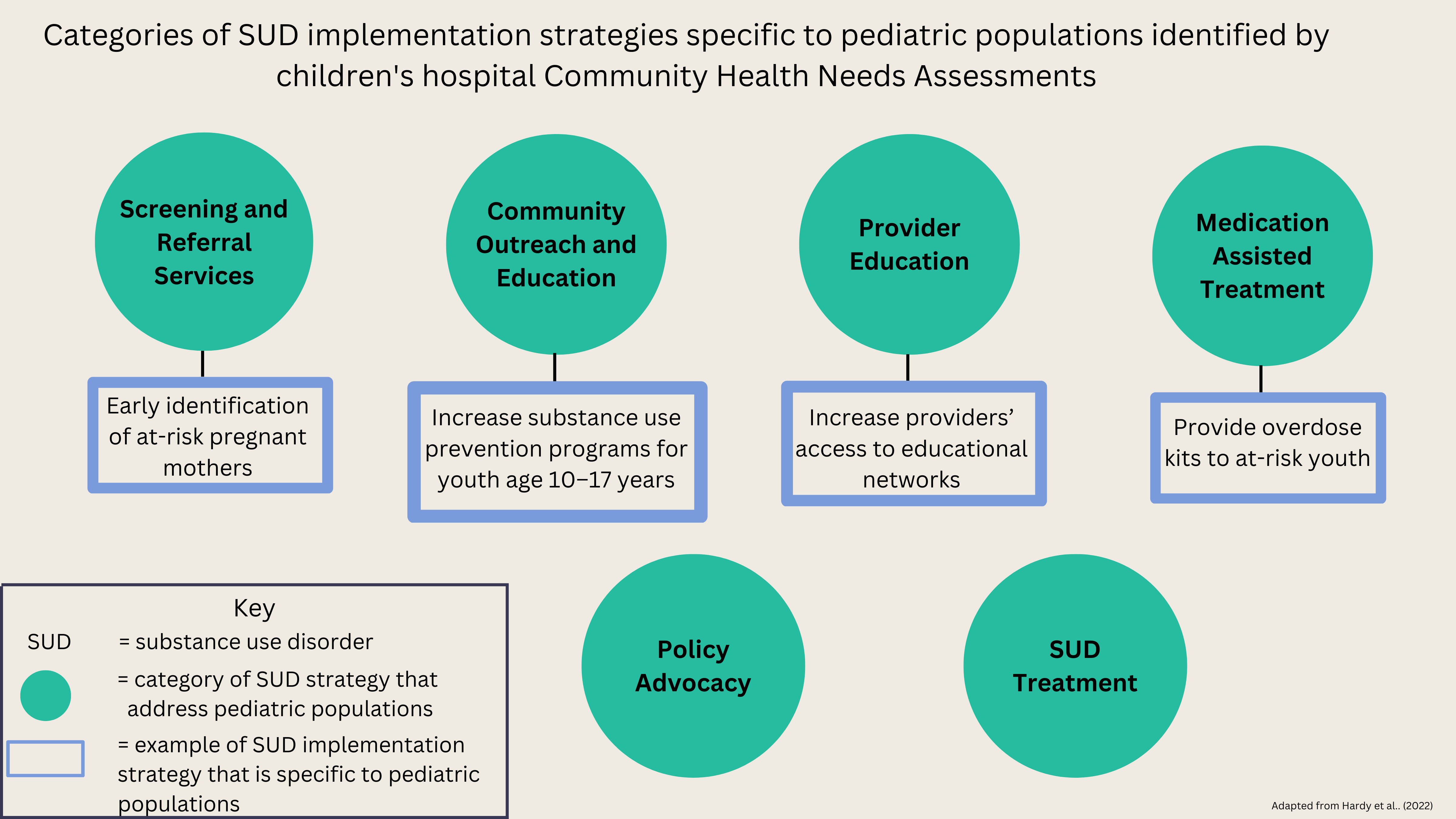

Forty four out of 206 children’s hospital needs assessments identified SUD as being a primary need among community members. Out of that sample, 27 hospitals reported implementing SUD strategies. Hospitals that implemented these strategies were more likely to be medium-sized (100-299 beds), compared to small (0-99 beds), and were more likely to conduct their CHNAs with another hospital. In fact, hospitals who conducted their CHNAs with another hospital had four times higher odds of offering substance use services, potentially due to serving a broader community and having more flexibility on how they spend their community benefit money. However, substance use services were underrepresented in areas with the highest need, including areas with relatively high income inequality. Hospitals in counties with higher overdose death rates were not more likely to implement SUD strategies. The 27 hospitals identified a total of 151 unique SUD strategies across 9 categories. But only 11 of these strategies, across 6 categories, targeted pediatric populations. The Figure shows 4 of these pediatric-specific strategies.

Figure. This Figure depicts the 6 categories of SUD implementation strategies that targeted pediatric populations. This Figure was adapted from Hardy et al. (2022). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Children’s hospitals are positioned to reduce addiction harm in their communities because they target people over the course of a lifetime. For example, if a hospital is trying to target adolescents, they may include interventions that address not only the adolescent’s needs but the needs of their family as a whole. Unfortunately, many of their current strategies are geared towards adults, potentially due to the fact that some hospitals may collaborate with organizations that primarily focus on adult populations. In addition to reducing the impact that adult substance misuse can have on a child’s overall health, children’s hospitals should develop and collaboratively implement more pediatric-specific programs. As the opioid epidemic persists into its third decade, it is even more vital that children’s hospitals focus efforts on education and prevention among their adolescent patients.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The needs assessment guidance provided limited instruction as to what constitutes a “community benefit,” so some substance use strategies could have gone undetected. The authors coded for substance use and mental health in separate categories, unless otherwise noted. This could have resulted in missed mental health implementation strategies that also included substance use strategies. The analysis examining characteristics of hospitals and communities who endorsed substance use strategies did not allow for causal interpretation.

For more information:

To learn about adolescent substance use programs in the Boston, Massachusetts area, visit the Boston Children’s Hospital website. If you are worried that you or someone you know is experiencing addiction, the SAMHSA National Helpline is a free treatment and information service available 24/7. For more details about addiction, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.