In China, smoking cigarettes is a very common addictive behavior among adult men. Gay and bisexual men are more likely to smoke cigarettes compared to the overall population. According to minority stress theory, the stress of being in a marginalized group can aggravate mental health issues such as depression, which can in turn increase the likelihood that gay and bisexual men would use substances as a means to cope or conform. While minority stress theory has received a lot of attention in North America, less is known about the relation between minority stress and negative health outcomes in Asian countries. This week, ASHES reviews a study by Jingjing Li and colleagues that examined the association between minority stress and cigarette use among gay and bisexual Chinese men in major Chinese cities.

What was the research question?

Does minority stress impact cigarette use among gay and bisexual Chinese men?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers cross-sectionally surveyed 538 gay men and 138 bisexual men from sexual minority organizations in Beijing, Wuhan, Nanchang, and Changsha that were located in, or near, college campuses. The survey asked respondents about past 30 day cigarette use, as well as their sexual orientation, sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., education, place of origin), depressive symptoms, and measures that tapped several dimensions of minority stress (e.g., everyday discrimination, rejection anticipation, adverse childhood experiences). The researchers used both logistic regression and structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the relationships between sociodemographics, depression, minority stress, and cigarette use.

What did they find?

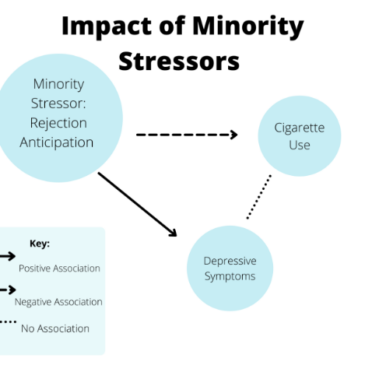

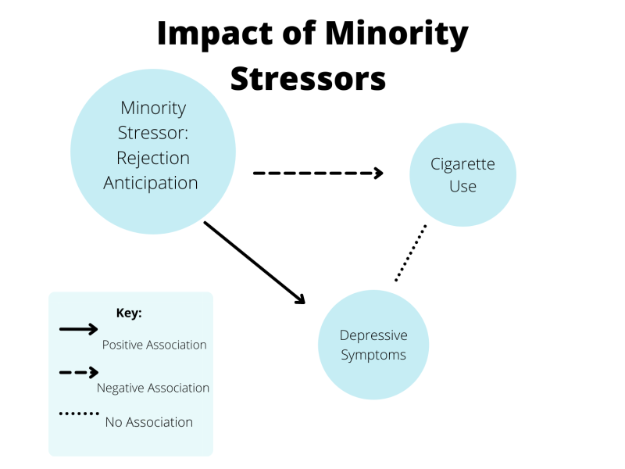

Bisexual respondents were more likely to report cigarette smoking (39.9%) than gay respondents (27.3%). Among all respondents, only one minority stressor (rejection anticipation) was directly, positively associated with increased depressive symptoms. However, contrary to expectations, rejection anticipation was negatively associated with past 30-day cigarette use (see Figure), and symptoms of depression were not associated with cigarette use. These findings suggest no indirect association between minority stress, depressive symptoms, and cigarette use.

Figure. SEM path model shows a positive association between rejection anticipation and depressive symptoms, and a negative association between rejection anticipation and cigarette use. No association was found between depressive symptoms and cigarette use. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The positive association between rejection anticipation and symptoms of depression could be the result of nonconformity of gay and bisexual people to Chinese moral standards, thus leading to marginalization or familial shame. However, and in contrast to minority stress theory, the researchers did not find a similar positive association between minority stressors and cigarette smoking. They speculate that the introduction of smoke-free laws in major Chinese cities since 2014, and a general increase in stigma towards smokers, had something to do with this. Perhaps bisexual and gay men stopped smoking in order not to be doubly stigmatized.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The sample was under-representative of Chinese people living in rural areas and from low-education, low-income backgrounds. Because the researchers recruited participants living near college campuses (most of which had implemented smoke-free initiatives), the smoking prevalence was relatively low. The use of cross-sectional data, especially for structural equation modeling analyses (which typically use longitudinal data), could lead to a misinterpretation of the causal relationship between minority stress and cigarette use.

For more information:

ILGA World – the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association fights for equality among the LGBQT+ population. The American Lung Association provides support for those who have a desire to quit smoking. For additional smoking self-help tools, please visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.