Sexual minority youth (SMY) experience higher rates of suicidality than their heterosexual peers. Previously, researchers have studied the high prevalence of suicide among SMY using a minority stress framework, which suggests that stigma and discrimination contribute to chronic stress, harmful coping patterns, and, ultimately, impaired health. Consistent with this framework, researchers have also observed higher prevalence of drinking among SMY. Heavy drinking itself increases the risk for suicidality among people generally, but could this relationship be especially strong among sexual minority youth? This week, The DRAM reviews a repeated cross-sectional study by Gregory Phillips and colleagues that looked into youth alcohol use and suicidality rates by sexual orientation.

What were the research questions?

What is the association between alcohol use and suicidality by sexual orientation among US high schoolers? Did the rates of drinking or suicidality change over time?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used local high school data (based around Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois) from the national Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) biennial survey. Within the survey, students were asked about their biological sex1, alcohol use, and suicidality which included suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts.2

The researchers used descriptive analyses to determine prevalence of suicidality and alcohol use by sex and sexual orientation at each time point, analyzed the trends in suicidality and alcohol use by sex and sexual identity from 2009 to 2017, and tested whether or not these trends differed for SMY and their heterosexual peers. They used odds ratios to estimate the odds of alcohol use and each suicidality outcome.

What did they find?

Of all the high school students, 6.7% reported being bisexual, 2.4% reported being gay/lesbian, and 3.9% were unsure of their sexual orientation identities. Over a quarter of students (29.6%) reported current alcohol use. Out of all the students, 16.3% had contemplated suicide, 13.7% had made a suicide plan, and 8.9% had attempted suicide.

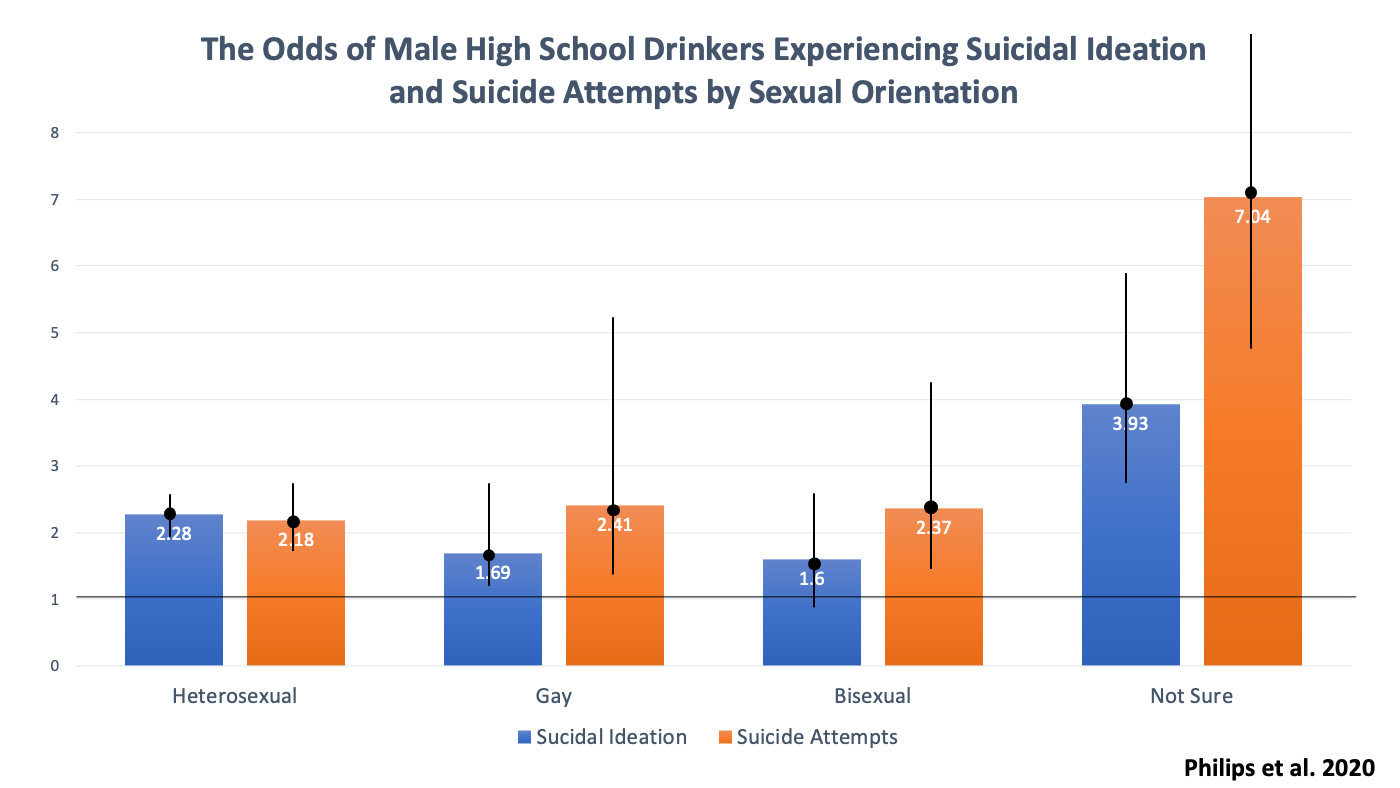

Current alcohol use was associated with higher odds of all three suicidality outcomes among male students, regardless of sexual orientation. The association between alcohol use and suicide ideation and attempts were stronger among males unsure of their sexual orientation than males in the other sexual orientation groups (see Figure). Female students who were current drinkers had more than double the odds of reporting all suicidality outcomes compared with non-drinking peers, but these odds were not different for girls with different sexual orientations. Overall, the rate of alcohol use decreased over time and the greatest decrease was among gay/lesbian and unsure youth.

Figure. Odds ratios (black circles) and confidence intervals (vertical lines) for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among male high school drinkers by sexual orientation, compared to non-drinkers who are the baseline at 1. Confidence intervals that do not intersect with the value of 1 indicate statistically significant differences. Phillips et al. used all the data from the whole study period, taking into account the years when constructing their models. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings suggest that boys who are unsure of their sexual orientation are at acute risk for suicide ideation and attempts if they are also drinking. Potentially, because they do not fully identify with either heterosexual or gay/bisexual kids, they don’t get the benefit of either group’s social support and drink to cope with their sense of isolation. Clinicians who treat sexual minority youth must show cultural competence in order to build trust and a productive therapeutic relationship. Clinicians should start by assessing their agency at all levels to identify needs and challenges to developing a welcoming environment and proper services for LGBTQIA+ youth. Their agency’s mission statements need to align with that commitment, and they should develop a plan to provide these services and resources to the youth. These plans should focus on creating both suicide prevention programs and alcohol use interventions specifically aimed at SMY.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

There was no measure of gender identity within the survey. It is possible that the associations between the measures would be different based on gender identity rather than biological sex. Additionally, suicidality and alcohol use were measured cross-sectionally using different times measures (past year versus past 30 days) making it difficult to analyze temporal relationships. Finally, the survey had no measure for whether students were “out” (i.e., open about their identity as an SMY), which could be relevant to both victimization risk and individual resilience.

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page. Advocates for Youth provides resources and education for professionals that serve LGBTQ+ youth. If you or someone you know are a young person who identifies as LGBTQ+ and are experiencing crisis, counselors are available 24/7 on the TrevorLifeline (1-866-488-7386).

— Karen Amichia

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] The question was worded, “What is your sex?” Answer choices were “male” and “female.” A gender identity question would have been worded, “What is your gender?” While sex is based on biological characteristics and is labeled at birth, gender is more personally/socially constructed. Some kids who were assigned one sex at birth might have provided a different response if asked about their gender.

[2] Any students who were missing alcohol use or suicidality data were removed from the dataset.