Exercise is associated with several physical benefits, such as improved sleep, higher energy levels, and reduced risk of chronic ailments such as heart disease and high blood pressure. Some work has found that exercise can be helpful for treating mental health disorders. More specifically, exercise, along with more traditional forms of treatment, has a high potential for treating substance use disorders. This week, The DRAM reviews a randomized trial by Jeremiah Weinstock and colleagues that examined the efficacy of an exercise program as an intervention for sedentary non-treatment-seeking adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD), with and without motivational interviewing and contingency management.

What was the research question?

What is the efficacy of an exercise intervention for sedentary nontreatment seeking adults with AUD?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used newspaper advertisements, flyers, Craigslist postings, and word of mouth to recruit 66 participants for a two-site clinical trial. Weinstock and colleagues recruited individuals who were between the ages of 21 and 65, sedentary (exercising less than two days per week), met the diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence, reported four or more self-reported heavy drinking episodes in the last two months, were not currently receiving or seeking any AUD treatment, and were cleared to engage in physical activity. Participants were randomized to one of two conditions. One condition received just a four month free membership to a YMCA (MO Condition). The other condition received a four month free membership along with two 50 minute motivational interviews and 16 weeks of individual contingency management exercise sessions (MI + CM Condition). In these sessions, the participant and the therapist created an exercise contract with three exercises that the participant agreed to complete within the upcoming week. The researchers then looked at the association between exercise condition and changes in drinking behavior and physical health outcomes from baseline to mid- and post-treatment.

What did they find?

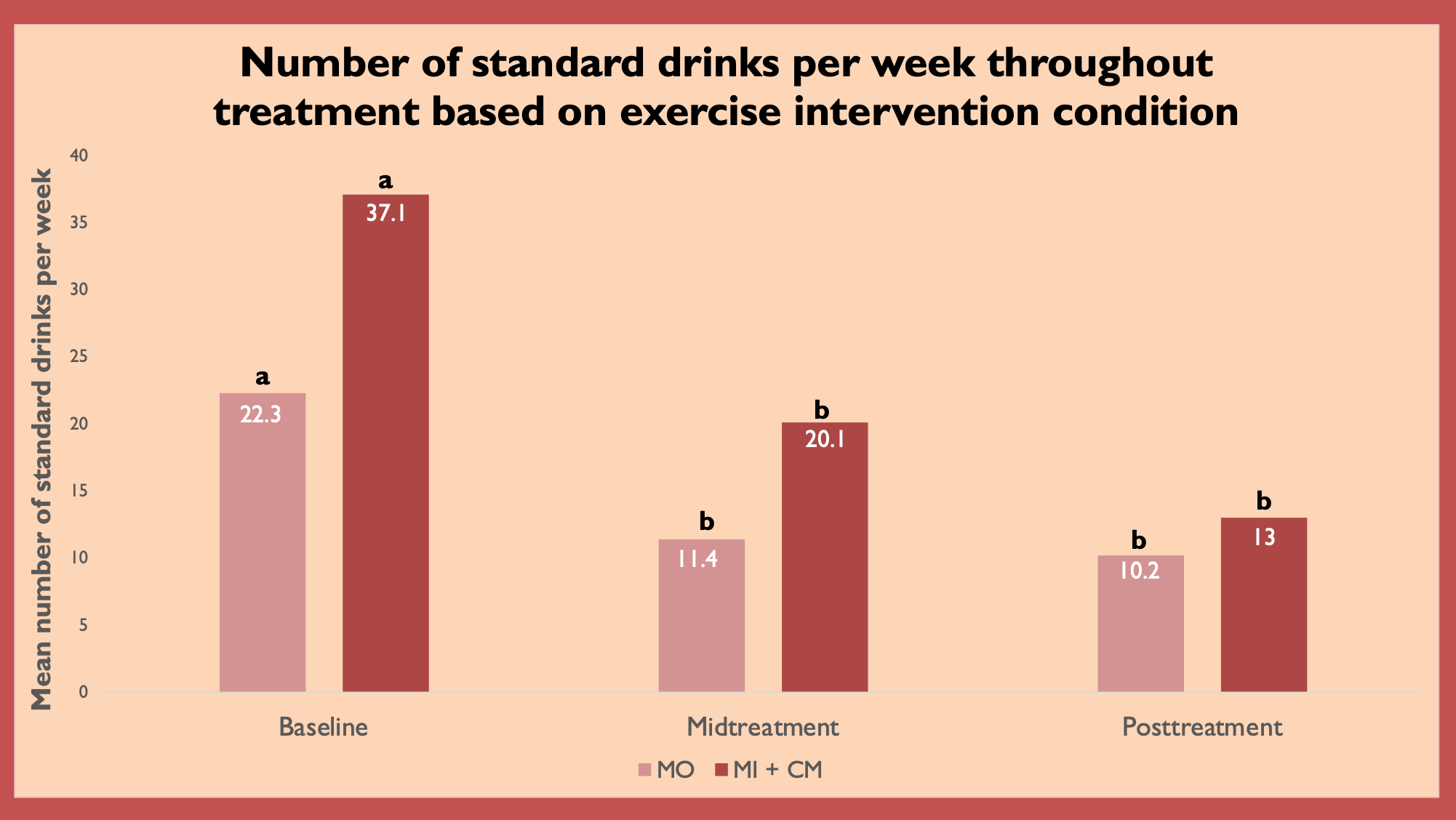

Participants in both groups reported overall improvement that they attributed to the intervention, with participants in MI + CM group reporting significantly greater positive self-reported improvement that they attributed to the intervention compared to participants in the MO group. In addition, participants in both conditions reported fewer binge drink episodes, fewer drinks per week, and fewer negative consequences associated with alcohol compared with their baseline drinking, with no differences between the two conditions on the extent of change). These drinking changes emerged by mid-treatment and were maintained until the end of treatment (see Figure). However, the group that received the motivational interviewing along with the gym membership had greater decreases in systolic blood pressure and some improvements in depressive symptoms compared to the group that only received the gym membership.

Figure. Mean standard drinks reported per week based on exercise intervention group (MO vs. MI + CM). Means with different letters (“a” versus “b”) are significantly different from one another. Figure adapted from Weinstock et al. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

It is important to understand the role that wellness, including physical activity, has in AUD treatment. The present findings suggest that it would be beneficial if typical AUD treatment included a guided exercise component. Reducing depression symptoms could help clients maintain the gains they made during AUD treatment, as previous research has found that major depressive disorder is associated with earlier drinking relapse for adolescents who had received treatment for AUD. Hopefully, learning about the benefits of exercise during treatment would help individuals carry that behavior forward in an effort to promote wellbeing and prevent relapse.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Though some forms of exercise, such as running or walking, are completely free, both of the intervention groups in the study received a gym membership which requires monthly payments. It is important to consider that not everyone has spare time or money to join a gym and some people have no safe space to run or walk. Therefore it is important to recognize that this intervention may only work for those with extra resources, and we should consider creating a version of this exercise program that is based exclusively on forms of exercise that are free and can take place in private, such as bodyweight exercises.

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

— Alessandra Grossman