Editor’s Note: In recognition of the ongoing importance of highlighting the vital contributions that Black academics make to addiction science, The BASIS is featuring the research and opinions of Black scholars of addiction. Today’s review is part of our Black History Month Special Series.

Longitudinal studies of gambling are rare. As a result, we know little about early age risk factors for the development of gambling-related problems in early adulthood (ages 18-29). Knowing more about risk factors from across the lifespan is important for prevention and harm reduction. This week, The WAGER reviews a study from Drs. Renee Cunningham-Williams, Hyun-Jin Jun, and Paul Sacco that examined the relationships between factors such as antisocial behavior, depressive symptoms, gambling behavior, and alcohol use as teens and gambling behaviors in early adulthood.

What was the research question?

Do adolescent demographic, mental health, and gambling experiences predict gambling participation and problems in early adulthood?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used data from a representative national study, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health (Add Health). The Add Health study follows participants from seventh grade (about age 12) through age 42. The survey has five data collection points, and this study used information from the first four of them, when participants were teens and young adults. Wave I was taken in 1994-1995 (when participants were in grades 7-12), Wave II in 1996 (grades 8-12), and Wave III in 2000-2001 (ages 18-26), and Wave IV in 2007-2008 (ages 26-32). The researchers then used multivariate logistic regression to assess the relationships between antisocial behaviors, depressive symptoms, gambling, and alcohol use at Wave III and gambling participation and problems at Wave IV. The two main Wave IV outcomes were problem gambling compared to non-gambling and non-problem gambling compared to non-gambling (i.e., gambling but not in a problematic way).

What did they find?

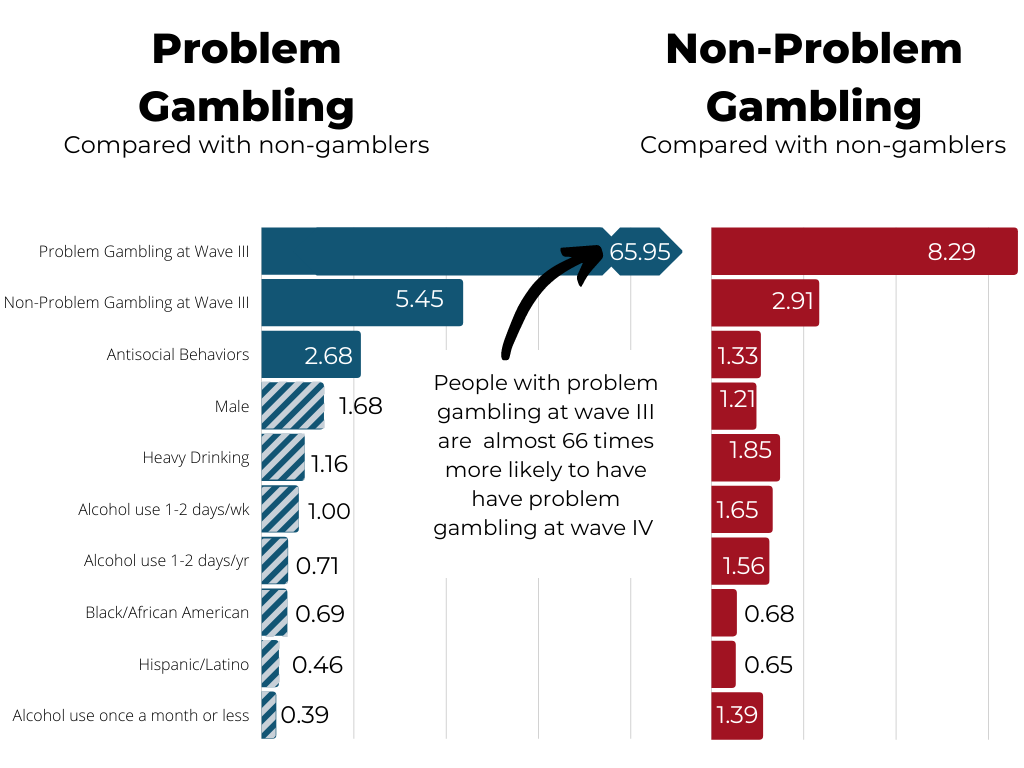

Non-problem gambling, problem gambling, and antisocial behaviors during teenage years (grades 8-12, approximately ages 13-18) increased later risk for problem gambling during young adulthood (ages 18-29). These three factors, heavy drinking, other drinking behaviors, and some demographic characteristics all increased the likelihood of non-problem gambling in young adulthood. (see Figure). Additionally, depressive symptoms as a teen did not predict gambling participation or problems as an adult.

Figure. Bar chart showing the odds ratios for the likelihood of problem gambling and non-problem gambling in young adulthood (Wave IV), based on adolescent experiences (Wave III), when compared to the non-gambling reference group. Solid bars show statistically significant odds ratios. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings suggest that we may be able to predict later gambling participation and problems based on teenage experiences. This supports allocating more resources into early awareness and prevention efforts that target diverse mental health and addiction-related experiences. Having this kind of advanced information could help make sure people get access to the resources they need before they develop a gambling problem. Understanding factors that affect the start and severity of Gambling Disorder helps everyone more effectively prevent it. The fact that depression did not emerge as a predictor is notable and inconsistent with other studies. This finding merits further investigation.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The study did not examine protective factors with theoretical and empirical support outside of the teenage behaviors they were investigating. There are other impacts, like religious participation or strong social ties, that might help protect against problem gambling. The risk pathways found here would be strengthened by an understanding of how they are impacted by the presence of absence of such protective factors. Additionally, the study relied on self-reporting to gather information. This could result in recall bias, or in underreporting to adhere to socially desirable characteristics.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a gambling problem? Visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for screening tools and resources. For additional resources, including gambling and self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Jennifer Scarborough, MS

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Charles Vorkoper February 24, 2021

An interesting connection for this study is that there is a higher relationship of these age groupings to suicide and addicted gambling. While I am depending on the memory of a retired mental health professional, my memory is sharp about issues like this. If I am correct, that would call for a need to look for a closer relationship between addicted gambling and suicide. My clinical experience matches these data when counseling lasts long “enough” with the problem gambler dying by suicide or threatened suicide –so that addiction and suicide may be twins.

I do not care whether this discussion comes from the problem gambling camp or from the suicidology camp. I think that the future of treatment rests, in an important way, on looking at this connection. My observation is that suicide and addiction are a part of the same process in humans. This would mean that they must be studied together.

There is also a very important concern in any research like this. The researcher’s definition of suicide and the researchers definition of problem gambling be articulated clearly and compared with the researchers well perceived beliefs of these two behaviors. The basic problem that is frequently one of perspective that is assumed for addiction and another perception for suicide. For example, if suicide is seen as tightly linked to depression (as a diagnosis) a research study assuming that addiction is highly linked to depression must form the core of research hypotheses. If one assumes that problem gambling is a learned behavior one cannot research suicide as something other than a learned behavior. While this may be seen as an issue for a 101 research class, it is an issue that I see going on in many studies that I have seen.

This is why I think this study is important. It offers a way to hold a behavior like suicide (note: my definition of both subjects is imbedded in this statement). and problem gambling side by side. This is critical for treatment as well.

Thanks.