Editor’s Note: In recognition of the ongoing importance of highlighting the vital contributions that Black academics make to addiction science, The BASIS is featuring the research and opinions of Black scholars of addiction. Today’s review is part of our Black History Month Special Series.

You arrive home late and start to get ready for bed. But then you see that your partner is still awake, and about to pour a drink. Do you join in? Research suggests that the answer will often be ‘yes.’ As couples become more interdependent, so do their drinking habits. In today’s DRAM, as part of our Black History Month Special Series featuring Black scholars of addiction we summarize a systematic review by Lydia Muyingo and colleagues on the degree to which romantic partners influence each other’s alcohol consumption.

What was the research question?

Is one’s alcohol use affected by how much alcohol their romantic partner drinks? Do men or women have more influence on each other’s alcohol use?

What did the researchers do?

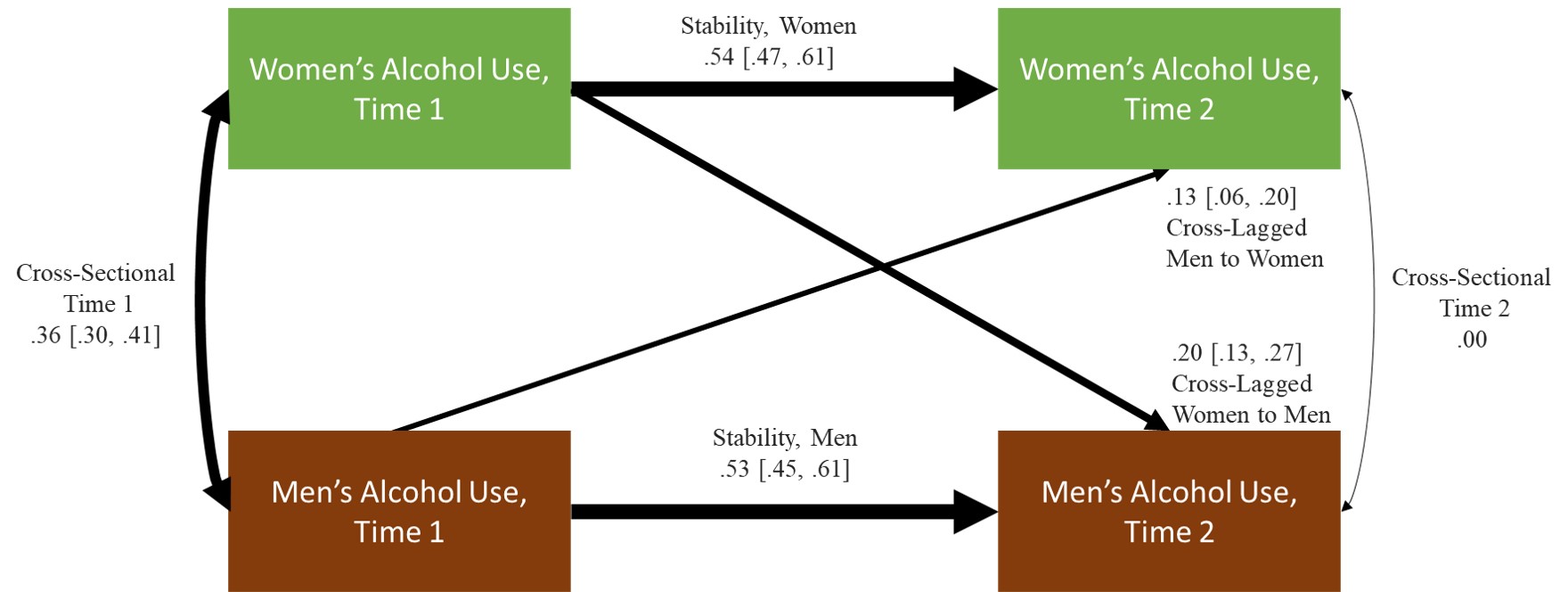

The authors found 17 studies (10,553 total couples) to include in their review, all of which collected data on how much both members of heterosexual romantic couples drank across multiple time-points. The average study length was 37.1 months. The authors recorded (1) the correlation between men’s and women’s drinking at a given time-point (the cross-sectional associations) to account for the tendency to partner with people who drink a similar amount of alcohol, (2) the association between people’s own drinking at adjacent time-points (the stability coefficients) to account for continuity in how much people drink over time, and (3) the associations between men’s drinking at an earlier time-point and the women’s drinking at a later time-point and vice versa (the cross-lagged effects): How changes in people’s drinking are affected by how much their partner drank at the previous assessment. It is necessary to control for cross-sectional and stability effects to accurately estimate cross-lagged effects.

Because some studies contained more than two assessments, the authors averaged effects across assessments within individual studies. Next, they entered study averages into a meta-analysis, which averages effects across studies, weighted such that studies that followed more couples had a larger influence on the results. In particular, the authors used two-stage meta-analytic structural equation modeling, enabling them to summarize cross-sectional, stability, and cross-lagged effects simultaneously.

What did they find?

The cross-lagged effects were statistically significant. Participants on average drank less at the follow-up assessment when their partner drank less at the previous assessment, and drank more at the follow-up when their partner had previously drank more. However, women had a larger effect on men than vice versa. Cross-sectional and cross-lagged effects were larger when studies measured the amount of alcohol use rather than severity of alcohol-related problems. See the figure for a breakdown of the primary results.

Figure. This path model moves left to right to show how romantic partners’ alcohol use at an earlier time-point (Time 1) influences use at a later time-point (Time 2). The results are based on an average of studies included in the meta-analysis, weighted by their sample size. The numbers to the left of brackets are correlations; the numbers within brackets represent the 95% confidence intervals of those correlations. Larger correlations are represented by thicker paths. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

People can put their romantic partners at either higher or lower risk for developing alcohol problems, depending on how much they themselves drink. Treatment providers, clinicians, and counselors should consider the social environment of patients with potential alcohol problems, and even to include their romantic partners in the treatment plan.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The attrition rate was substantial in all studies (36.8% of participants dropped out of studies before the final assessment on average). Although attrition rates did not explain variability in study findings, other research suggests that the magnitude of attrition per se does not predict to what degree longitudinal studies of alcohol use produce inaccurate estimates. All of the included studies may have distorted results to the extent that those who dropped out have different drinking behavior on average than those who completed all follow-up assessments. Also, because the studies only sampled heterosexual couples in North America and Western Europe, readers cannot readily generalize these findings to other populations.

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For drinking self-help tools, please visit The BASIS Addiction Resources page.

Health professionals and addiction specialists have been increasingly focused on mental health as it pertains to COVID-19. They have assembled substance use resources specific to COVID-19-related concerns, as well as resources on alcohol use in general, which can be found on the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites.

— William McAuliffe, PhD

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Megan Petra February 3, 2021

Nice job in explaining continuity & cross-lagged effects, and meta-analysis. Those are difficult topics & the writer made them both accessible!