Editor’s Note: This editorial was written by Karen Amichia, a Research Coordinator at the Division on Addiction. Ms. Amichia prepared this editorial as part of our Special Series on Race and Addiction. We thank her for generously sharing her story with our readers. We hope that readers with the same kinds of experiences will feel less alone after reading this piece. This piece includes descriptions of sexual violence and readers should use their best judgement in reading this story.

Who Protects US?

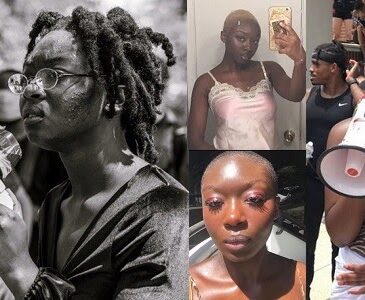

Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Salau was a 19 year-old Black activist organizing and protesting for Black lives in Tallahassee, Florida. On June 6, just a couple days before my 23rd birthday, Oluwatoyin wrote a series of posts on Twitter giving the detailed accounts of her sexual assault. She was found dead after being missing for several days following her posts.

Oluwatoyin had used her platform to center trans, non-binary, queer and femme Black people. She implored us not to forget those most at risk, those endangered by intersecting racism, homophobia, and transphobia. She begged us to say their names, remember them, honor them, uplift them, and protect them.

But who protected her?

She had felt she couldn’t go home – she wasn’t welcome, or she didn’t feel safe. And after days of protesting, she went to a church because she needed housing and a safe place to sleep. And in the church, she met a Black man who said he could provide that safety. She thought he was a man of God.

But he instead assaulted her. And when she escaped, she went to Twitter to out him and gave detailed descriptions of him, where he lived, and what he did to her.

She was met with disbelief and pointing fingers. Why go to Twitter? If he really did all that, how are you so comfortable speaking out publicly? Why not go to the police?

But ask yourself, does it make sense for someone actively protesting police and state violence to feel comfortable enough to turn to them with something so personally traumatic?

Even those who aren’t actively protesting often feel unable to go to law enforcement.

I know, because during my junior year of college, when I was 20 years old, I was raped.

I went on a date with a man I had met on Tinder. It was actually our third date. We smoked some weed, listened to music, and just vibed. I really liked him. After that we went back to his room to watch a movie and cuddle. No big deal, I had been in his room before. I’d be fine.

Things quickly got heated between us and clothes came off and I was enjoying myself. But I did not want to have sex, I told him that. He knew that. But I was high and it felt good and he used the pleasure that I felt to overwhelm me, to pressure me. I said no, over and over, but he continued. I cried, silent, suffocating tears. But he continued.

It wasn’t until I felt clear headed enough to push him off me that he finally stopped. I put my clothes on and called an Uber. He walked me to the car and hugged me goodbye. I let him hug me. I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t even feel like my body belonged to me.

I chose not to press charges. Not because I didn’t think what had happened to me wasn’t serious or that it didn’t affect me at all, but because I didn’t think there was a chance of me actually getting any justice.

I could imagine what officers, lawyers, a judge, an entire courtroom would say to me. It was your third date, you smoked beforehand, then went to his room. Why would he not think this was an okay thing to do?

I thought of everything they could say about me to attack my character and my womanhood. I thought about the fact that as Black woman, I am hyper-sexualized by the world with no effort of my own. I thought about the fact that I was just another Black person smoking weed (illegally at the time) and reporting could potentially put myself in trouble. I thought about the fact that Black women rarely, if ever, get justice for the sexual assaults they report. I thought about the fact that a public trial would blow back not only on me, but on my entire family. I thought about the fact that taking a semester off to heal wasn’t possible because I couldn’t waste all the money my parents struggled to put together, and the thousands of dollars I borrowed, for my education. I thought about the fact that the world would suddenly have an opinion about how I dealt with something so traumatic.

I thought about the fact that the man who raped me was Black, and I wasn’t sure what the police might do.

Although we can’t know for sure, a part of me feels as though Toyin thought a lot of this too. And it hurt me so deeply to see all of the comments questioning her story and her truth, questioning whether this story was created to further divide the Black community.

I felt the pain of every comment from every Black man who attacked the Black women sharing and amplifying Toyin’s story. I still feel the pain of being told this isn’t important right now and we need to be unified against the White supremacist state, as if misogyny and rape culture aren’t integral functions of White supremacy.

A week or two after I was raped, I requested an appointment with the emergency counselor on call. She was a White woman. I was hesitant to have her as a counselor, but I figured at the end of the day, she was trained to do this job so I’ll give it a try. I didn’t say too much on the topic of the assault at the time because I still wasn’t fully prepared to have the conversation. But I scheduled weekly visits with her to try to get better.

Between my second and third visits, I got a tattoo on my thigh that says “SURVIVOR” as a reminder to myself. I expressed the anxiety of my parents knowing about this new tattoo as they are rather traditional people. The counselor responded with, “Well at least you’re really dark so it’s not like the tattoo will be that noticeable anyway.”

I was shocked. She said it so calmly and even with a smile, as if what she said was absolutely correct and okay to say. I didn’t even know how to respond. I was lucky the session was almost over and I left soon after that.

The comment came from such a deep place of ignorance. Who says that when Black people have been getting tattoos since the beginning of its invention? It literally made absolutely no sense.

I didn’t return to counseling after that. I didn’t see the point of coming to a counseling session to discuss the violence that happened against me as a woman, only to have to fight against the ignorance happening against me as a Black person. I couldn’t even switch to another counselor on campus because my school only had one Black counselor on staff and she was always booked.

Educating health professionals on implicit bias is important, especially in the medical and mental health fields. However, frequent positive contact with Black people is especially crucial in reducing bias among non-Black health professionals. This is not the first time I have had an experience like this, where my race became a factor in my treatment unnecessarily, and it wasn’t the last time either. In fact, racism in healthcare is a very common occurrence for Black people, and Black women especially. Additionally, institutions need to employ more Black health professionals. My campus only had one Black mental health counselor (whom we had to fight to get during my freshman year at the school) and I wonder how my recovery could have gone had I been able to speak to someone who actually understood where I was coming from.

To be a Black woman is to stand at the intersection of two marginalized identities: Blackness and womanhood. Every day in this country I am fighting for the liberation of my Black people as a whole, and yet every day I am also fighting against the violence against me as a woman from both White society and Black men. It is exhausting.

The rage and pain I felt hearing about Oluwatoyin made me incapable of focusing for a week. I saw myself in her. I saw my friends, of whom more are survivors than not, in her. I made it to my 23rd birthday, but she wasn’t given the chance.

Based on reported assaults, 18.8% of Black women in the US will experience sexual assault, but only 1 in 15 Black women actually report their assault. A deep-rooted, silencing culture exists within Black communities to perpetuate this idea of strength and resilience amongst Black women. Our identities are so tied up in the endurance of pain, the violence against us is normalized and we are told to take a backseat.

I love being a Black woman and I wouldn’t change it for anything. The most influential people in my life are all Black women. We are amazing.

We are Black.

We are women.

We are humans.

We deserve to have our voices heard and to be uplifted and supported the way we support other women and our Black men.

We deserve more.

Oluwatoyin Salau. #SayHerName

Please feel free to comment on this editorial below or email us at info@divisiononaddiction.org.

Additional Resources

- If you want to learn more about finding a Black therapist virtually, click here. This piece by René Brooks also talks about the benefits of Black people finding Black therapists.

- Depressed While Black is an online community, in-progress book, and charitable initiative created by Imadé Nibokun Borha.

- RAINN offers support to sexual assault survivors and their loved ones. You can find them here, or call (800) 656-HOPE (4673), or use their live chat feature.

- If you want to donate to causes that support Black women and girls, some options are Justice for Black Girls/Oluwatoyin Salau Freedom Fighters Fund, Black Women’s Blueprint, and the Trans Women of Color Collective (TWOCC).

Funding Statement

The Division on Addiction currently receives funding from the Addiction Treatment Center of New England via SAMHSA; The Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility (FAAR); DraftKings; the Gavin Foundation via the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); GVC Holdings, PLC; The Healing Lodge of the Seven Nations via the Indian Health Service with funds approved by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health; The Integrated Centre on Addiction Prevention and Treatment of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Hong Kong; St. Francis House via the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Bureau of Substance Addiction Services; and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas via MGM Resorts International.